In the heart of the Netherlands lies its largest national park — Het Nationale Park De Hoge Veluwe.

Spanning forests, sand dunes, and vast heathlands, it is a landscape where the wild feels carefully preserved yet surprisingly untamed. We spent a day hiking through this remarkable park, discovering quiet beauty, unexpected challenges, and a few memorable encounters along the way.

From Emmen, where we had stayed the night before, it was a drive of just under 130 kilometers southwest — about an hour and a half by car. We entered the park through the gate and parking area near the village of Hoenderloo, one of three gates surrounding this vast reserve.

De Hoge Veluwe is the second oldest of the Dutch national parks and covers an impressive 5,500 hectares — about one hundred times the size of Shinjuku Gyoen in Tokyo. To give a sense of scale only Tokushima locals might understand, it’s roughly the size of the forested areas of Katsuura Town, perhaps just a little smaller.

Because it is a national park, the entire area is enclosed by fences, and entry requires an admission fee — €13.05 per adult plus €4.65 for parking. The park has fixed opening hours that change with the seasons: until 9 p.m. in August, 10 p.m. during the long days of June and July, but only until 6 p.m. in the short winter days.

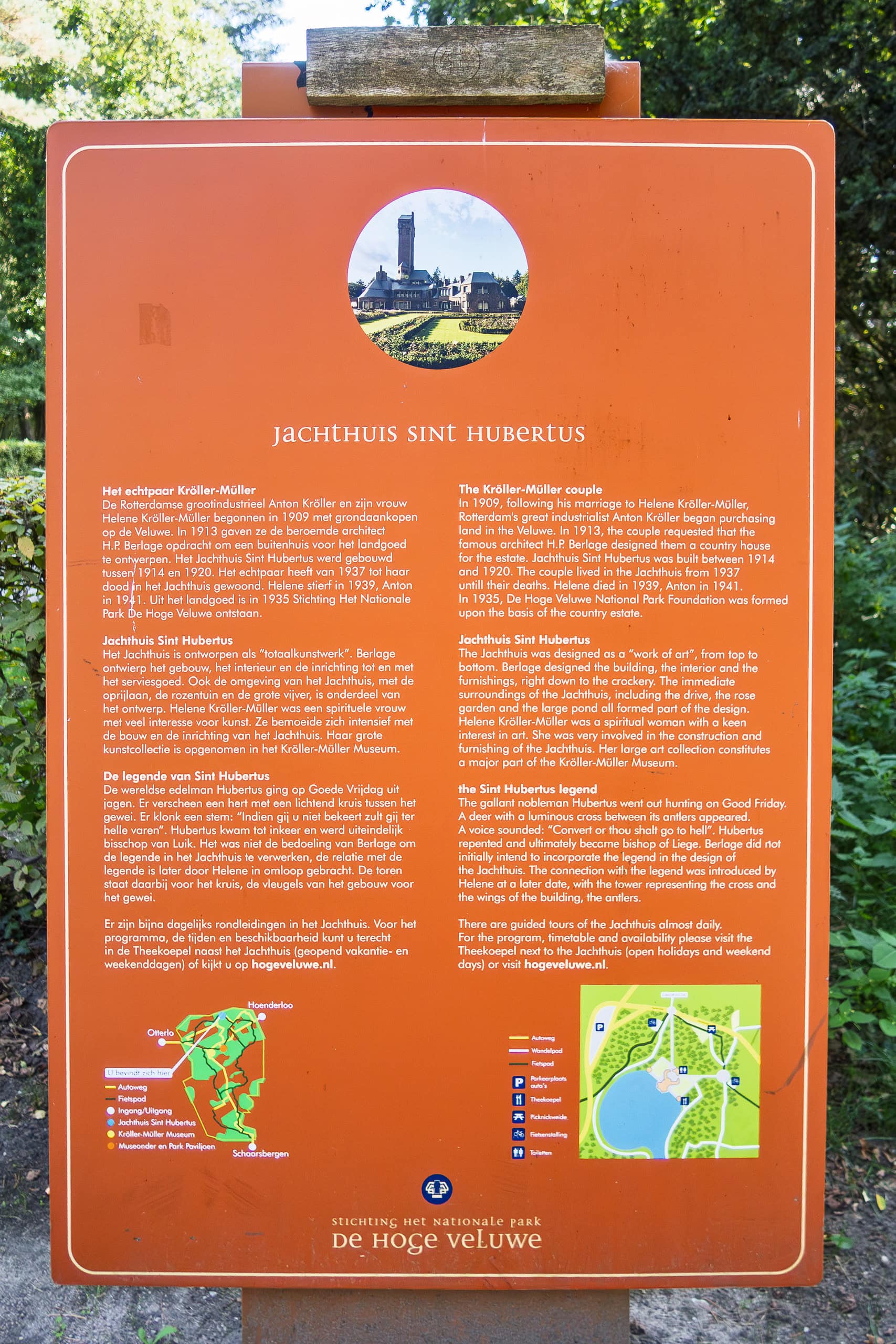

It’s remarkable to think that all of this vast land was once privately owned. In the early 20th century, it belonged to the industrialist couple Anton and Helene Kröller-Müller and their family, who used it as a private hunting estate.

The couple were also devoted art collectors, and their collection is now displayed at the Kröller-Müller Museum, located in the center of the park. The museum is famous among art lovers for holding one of the world’s largest Van Gogh collections — second only to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

However, because it’s quite remote and public transport from Amsterdam is inconvenient, the museum is hard to reach for short-term travelers.

Our purpose this time, though, was not the museum but hiking, so we decided to save that visit for another occasion.

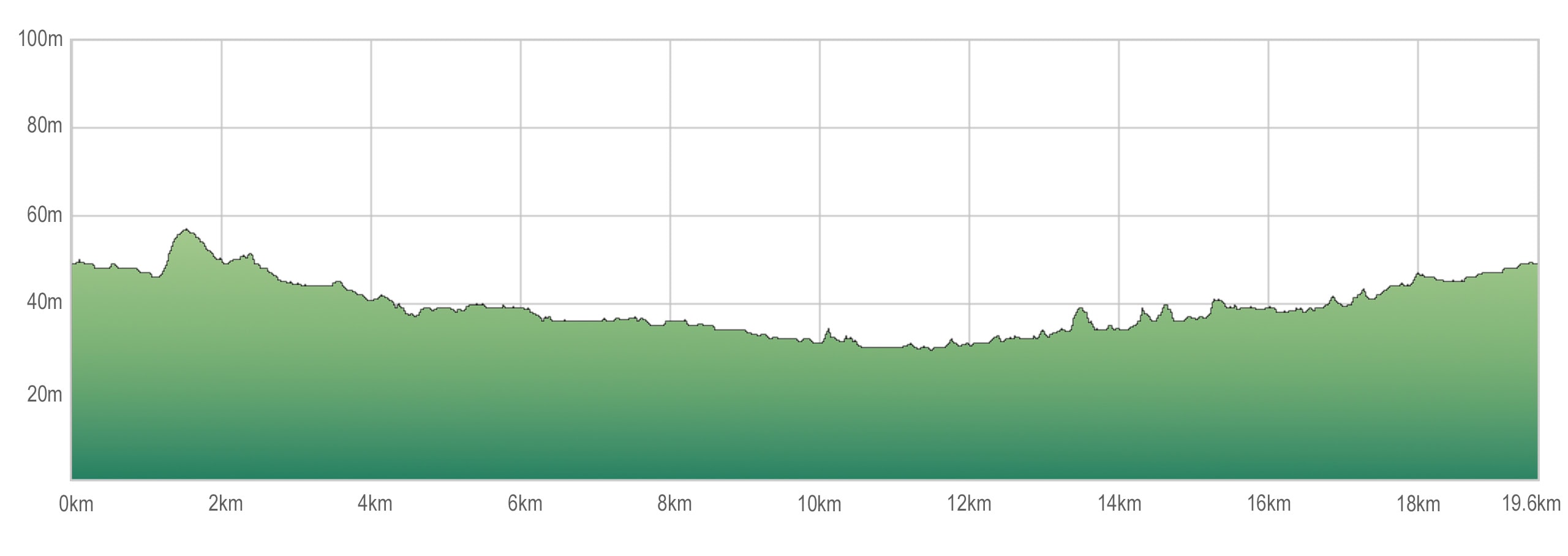

The main hiking trail loops around the northern third of the park and is about 20 kilometers long. In the Netherlands, elevation gain is almost nonexistent, so the walk should take roughly four to five hours.

When we arrived at the gate around noon, the parking area was quiet and nearly empty.

Just inside the gate, a broad tree-lined road leads into the park. Beside it, hundreds of free rental bicycles were parked in neat rows. No paperwork, no fees — visitors simply pick one and ride away. At this Hoenderloo gate, all the bicycles are standard models, but at the main gate, where the visitor center, museum, and restaurant are located, there’s a wider range — tandems, family bikes, even special designs that can carry a person in a wheelchair.

Most visitors seemed to be happily exploring the park by bike — their own or these free rentals — and throughout the day, we never saw a single person hiking on foot like us.

That doesn’t mean the park isn’t suited for hiking, though. Separate from the cycling routes is a network of unpaved walking trails and nature paths, allowing you to enjoy the forests and open heathland without worrying about bicycles rushing past.

Soon we left the tree-lined road and entered one of the park’s main highlights — a vast, open plain stretching as far as the eye could see.

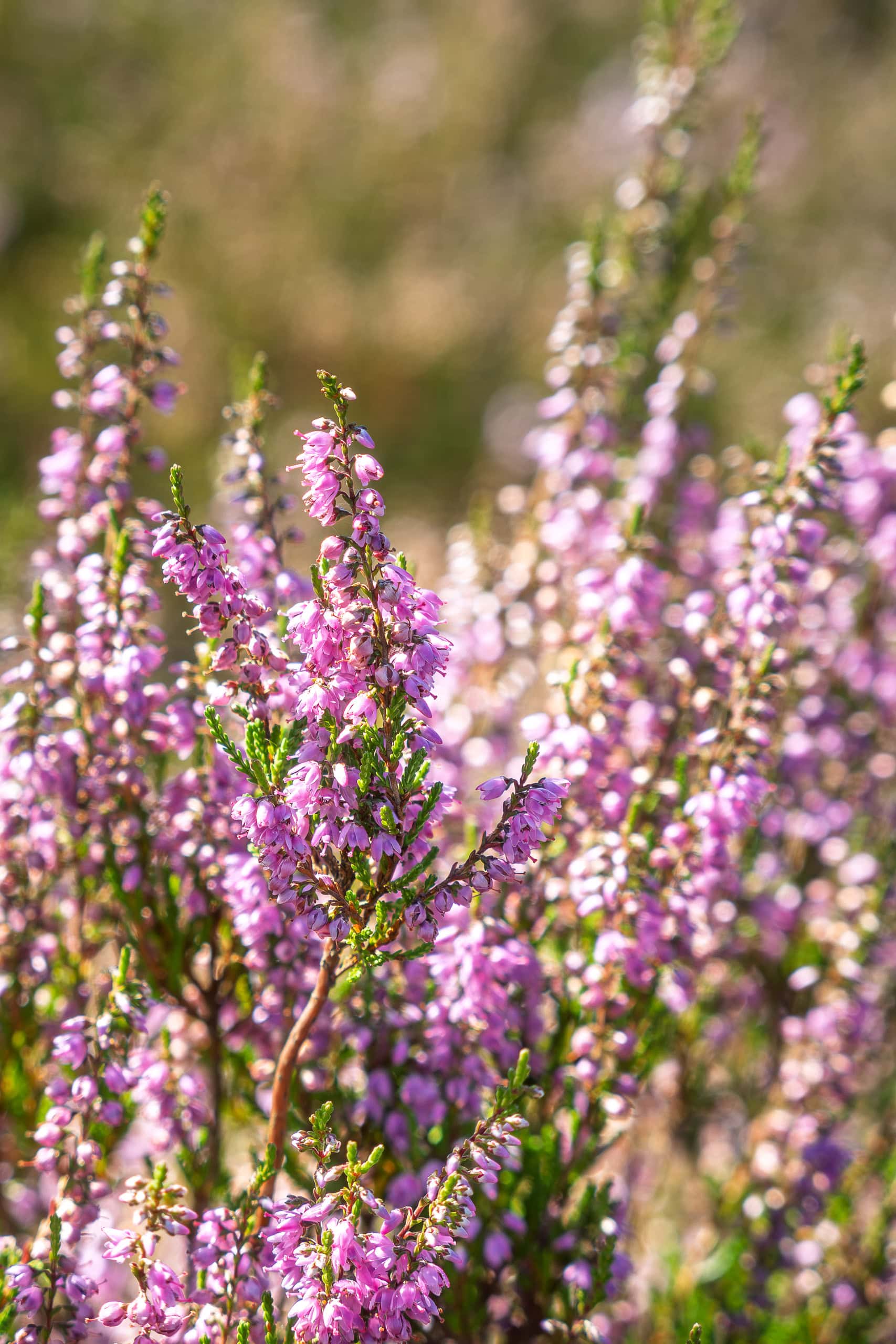

The heather was in full bloom, spreading carpets of red-purple across the landscape, while the sky above was an endless, unbroken blue. The horizon is something you can see almost anywhere in the Netherlands, a country where flatness itself feels like part of the scenery.

Here too, the ground was fine sand, as if we were walking along a beach. The trail was deep, bare sand with no grass at all, and simply walking on it felt like running drills on a sandy shore — the kind sports teams use for strength training.

It was unexpectedly hard on the legs, and before long we were both thinking, “Wait, wasn’t this supposed to be a relaxed walk?”

On the eastern half of the route, patches of woodland interrupted the wide heath fields. The trees were mostly broadleaf — many kinds of oaks and other acorn-bearing species. Beneath them, the forest floor was covered with moss.

Though dry in summer, I could easily imagine how lush and velvety it must look in the wetter months, shimmering with moisture under the autumn mist. I would love to return one early morning and see it cloaked in fog.

Deer, large goats, and wild boars are said to live throughout the park. These animals were originally released by the Kröller-Müller family, who once owned the land, to create a private hunting ground. Over time they became wild and established lasting populations. Wildlife watching is one of the park’s main attractions, but recently their numbers have dropped sharply.

The reason: wolves.

Yes — wolves now roam somewhere within the park. They weren’t introduced by the former owners, nor have they lived here naturally for centuries. In recent years, environmental or rewilding activists secretly released them, thinking it would help restore balance to nature.

In Japan, too, there are ongoing debates about overpopulated deer and boar and the idea of “releasing wolves into the mountains” as a natural solution. In the Netherlands, that idea has already been put into practice — for better or worse.

The result has been predictably complex. Wolves, impartial in their menu choices, began hunting not only invasive animals but also the park’s protected deer and wild goats. Soon they started preying on livestock — sheep and calves — in nearby farms. Even though the national park is surrounded by strong fences and nets, wolves somehow escaped.

Astonishingly, it’s said that some pro-wolf activists deliberately cut holes in the fences to let them out. As a result, the damage to farmers, whose animals are their livelihood, grows worse every year.

Animals that no longer belong to a place cannot simply be forced back because they once lived there hundreds of years ago. The environment, society, and daily life have all changed. Why expect it to work? What remains now are the unintended consequences of a shallow idea, spreading even as we speak.

Along our route stood one of the wildlife observation huts, so we stepped inside to take a look. As expected, there was no sign of any animals through the viewing slits. With fewer creatures in the park and the sun blazing overhead, it was no surprise that nothing was moving.

Still, since we live in Tokushima, Japan — where deer, boars, and pheasants casually cross our path almost daily — we weren’t particularly disappointed by the quiet.

Walking through the forest was pleasant enough, but the moment we stepped out of the shade and onto the sandy heath, everything changed. The summer sun was especially strong that day, and we had started our hike in the early afternoon — exactly when the heat was at its peak.

There were no shops or kiosks near the gate where we had entered (when will I ever learn?), so we had made the foolish mistake of setting off without water. By the time we were crossing the heather fields, both of us were already beginning to feel anxious. Fortunately, about a third of the way along our route, we reached the central visitor center area, where both the café and the shop were open — a huge relief.

We went into the café, which was quiet now that lunchtime had passed, and chose an outdoor table with as much shade as possible.

Wherever you go in the Netherlands, the waiter seems to appear instantly for drink orders, and of course this time there was no hesitation — cold drinks, please.

We were hungry, but the heat made it hard to imagine eating sandwiches or burgers. Instead, we studied the dessert menu: chocolate cake, pie, all far too heavy. Oh, how I longed for zaru soba or somen — something light and refreshing.

In the end, I ordered the simplest thing I could find, a strawberry ice cream sundae. The presentation was adorable, and the combination of strawberries and fresh basil — something I had never thought of — was a delightful surprise.

Meanwhile, my indestructible travel partner, always unfazed, refueled with a Dutch-style pancake — generously loaded with cheese and bacon.

Next to the café, the visitor center shop mostly sold museum-style souvenirs, but in one corner stood a small fridge with cold bottled drinks. I sighed with relief. We stocked up on water and tea this time before setting off again, heading westward into the park.

The western area was nothing but sand — everywhere.

The few trees that stood were mostly pines and their relatives, and the landscape felt like walking across a parched golf course made entirely of bunkers. The surroundings were desolate, and perhaps it was only my imagination, but the sand even seemed deeper now, making every step heavier.

The sun reached its fiercest point of the day, beating down mercilessly with no shade at all. The white sand reflected the light upward, so it felt as though we were being scorched from every direction.

Thankfully we were now carrying plenty of water. Without it, crossing this stretch could easily have ended with one of us collapsed on the trail.

We had both long since grown tired of the scenery, moving forward in silence, step after step. Eventually, after circling half of the western area, the landscape began to change. More trees appeared, and the path led us into a forest of conifers.

At the far side of the park’s center — opposite the main gate — a large pond came into view. People were relaxing along its banks. Facing the water stood a stately mansion with a tall central tower and perfectly symmetrical wings.

This was Jachthuis Sint Hubertus, or Hunting Lodge Saint Hubert, once the residence of the Kröller-Müller family, the park’s original owners.

The house’s architecture was strikingly unique — hardly what one would call “a normal home.”

But that, of course, suited the couple perfectly. As passionate art lovers, they commissioned the entire building as a work of art in itself, custom designed down to the last detail.

Guided tours of the interior are available, but advance reservations are required, and by now it was nearly 5 p.m.

Luckily, a small snack stand beside the lodge was still open.

“We only have cold drinks and ice cream left,” the staff said apologetically — which was exactly what we wanted. I downed an orange soda and a cola popsicle, the cold sweetness reviving my overheated body. I could almost feel it soaking into my bones. Then I had a second orange soda, just because.

The final quarter of our route led back into the park’s eastern section.

The landscape changed again — from pines and dry sand to oaks and broadleaf trees. The air felt instantly cooler, at least five degrees lower, and somehow even the air smelled fresher. Long live the land of moss and deciduous trees.

With renewed energy, we strode cheerfully along the oak-lined road toward the gate where we had started. Just as we were about to finish our hike, something suddenly appeared from the right side of the path, a little way ahead of us.

Standing there on the same trail was a small deer.

Judging by its size and antlers, it must have been a ree — a roe deer, or noro-jika in Japanese.

Startled but thrilled, we stopped quietly, holding our breath. The little deer, seemingly unaware of us, walked calmly across the path and disappeared into the bushes on the other side.

A perfect surprise to end the day. Thank you.

De Hoge Veluwe

| Distance | 19.6 km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 58 m / 58 m |

| Time | 5 h 49 m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 54 m / 24 m |

Comments