When Finding a Bed Felt Impossible

We honestly thought we might finally have to do stealth camping when we looked at the route map around the Ogatsu Peninsula 雄勝半島.

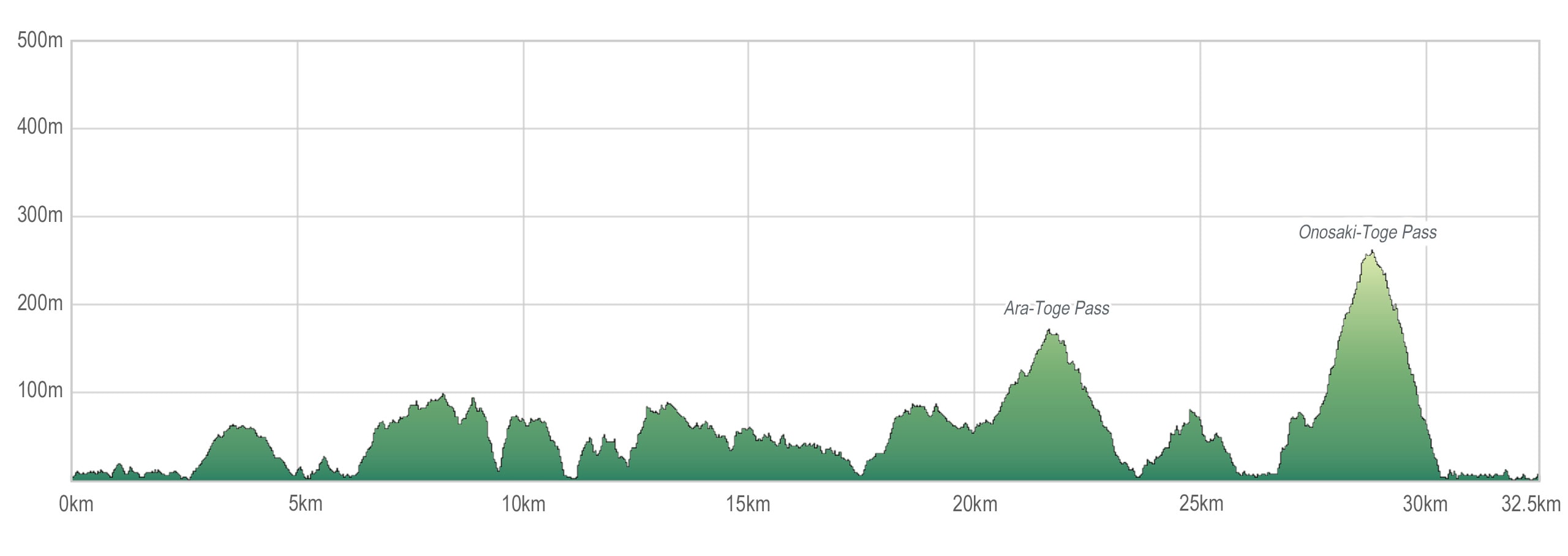

On Day 16 of our MCT thru-hiking, our plan was to walk all the way around the peninsula to Hamanasu Café はまなすカフェ by Lake Nagatsuraura 長面浦, crossing the Onosaki Toge Pass 尾ノ崎峠 at the end.

(Nagatsuraura is actually an inland sea, but the English map published by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan labels it as Lake Nagatsuraura.)

But there were absolutely no accommodations anywhere around the lake. Our target distance for the day was about 32 km — the longest I could possibly handle with crossing a few low mountains included. All the other lodging options were either far too close to our starting point or far too far for my ability.

Just as I was about to give up on finding a place to stay, I zoomed out on Google Maps and realized our goal point wasn’t actually that far from downtown Ishinomaki 石巻市 — the same port city where we had taken the ferry to visit the island of cats a week ago.

It was only a straight 20-minute drive west along the Kitakami River 北上川 to the city’s shopping district, where several business hotels were located.

I searched for taxi companies in Ishinomaki and called one to ask if they could pick us up at our goal point by Lake Nagatsuraura. The booking clerk immediately replied, “Sure! What time, and where exactly by the lake?”

And just like that, our toughest accommodation problem was solved.

Walking Behind the Seawalls

Early this morning we finally checked out of Hotel El Faro, our cozy trailer-house stay for the past four nights.

We called another local taxi to pick us up and asked the driver to stop at a nearby convenience store before leaving Onagawa. There we shipped out our supply boxes and stocked up on food and drinks for the day. Fully prepared, we got back into the taxi waiting in the parking lot and headed back to yesterday’s goal point, Michinoeki Ogatsu.

From the Michinoeki Ogatsu, we could see new seawalls under construction all along the coastline in the direction we would be walking.

From the MCT official map book, we expected that today’s entire route — except for the final Onosaki Toge Pass trail section — would be along a narrow road without sidewalks. Remembering how annoyed we had been yesterday by trucks roaring past, we felt a little discouraged even before starting.

But as soon as we began walking, we realized it was Saturday, which meant most of the public construction work was on break. Our guess proved right: we saw only a few trucks, and many roadside closures along the route were temporarily open.

For a while the trail ran right beside the sea. Most of it was already walled off by high concrete barriers, and the few open stretches where we could glimpse the bay were also under construction.

After the tsunami, all fishing ports along the Pacific coast of Tohoku were placed outside the seawalls, with access only through a limited number of gates.

Because the MCT route had been mapped before the seawalls and new roads were built, it often passes through these port areas. Sometimes we had to go through the gates to enter the ports to follow the route and catch a view of something other than concrete walls.

Eventually the road led between Japanese-cedar forests and mountain slopes. It was quiet, with only a few cars passing.

We were grateful for the constant shade on such a sunny day, but after a while the lack of views on either side became monotonous.

Just before Ogatsu Elementary School, we saw movers carrying furniture out of a small post office. A vending machine stood out front, so we grabbed some drinks — unaware that this would be the last vending machine for nearly 15 km…

Through the quiet hamlets

The paved road we were following kept to the same 70~80 m altitude line, but just before reaching an old, closed elementary school that had been renovated into dormitory-style lodging, an MCT signpost directed us to leave the road and descend toward a small fishing hamlet by the beach called Kuwahama 桑浜.

We made a quick stop at the former-school dormitory called MORIUMIUM, hoping to find a bathroom or maybe some snacks and drinks. But much of the facility still looked under DIY renovation and was closed off. Empty-handed, we returned to the signpost and headed down the long staircase.

As we walked along the narrow lane between houses, we saw a few elderly locals working outside their homes and storage sheds.

Normally we greet people when they glance our way, but this time the atmosphere felt unfriendly — or at least indifferent. Still, we reminded ourselves not to take it negatively, as this was during the COVID period.

Not wanting to bother anyone, we quickened our pace and kept walking.

The route didn’t linger in the hamlet and soon climbed back up on a natural trail behind the beach.

Along the forest path we came upon a shrine called Shirogane Jinja 白金神社 and stopped for a short visit.

Behind the shrine, a path led to the tip of the cape, where a small lighthouse stood. From there the Pacific Ocean spread out calm and beautiful before us, stretching endlessly into the horizon.

One thing we noticed today was how much clearer the seawater is around the Ogatsu Peninsula compared to the southern parts of Miyagi.

I remembered chatting with a local grandpa a few days earlier: when I told him we were heading north, he said, “Oh, good. The northern areas have much clearer seawater.”

Eventually we emerged into another fishing hamlet on a different beach. Here, many houses had traditional slate roofs made from the same local black rock used for inkstones. For me it was the first time seeing this kind of roof in Japan, but for Erik it felt familiar — he said such roofs are very common in Europe.

The trail then climbed back up through the trees to rejoin the main road. From time to time we passed other small hamlets, but mostly we walked in silence through the forest. Before long, the monotony set in — we were really getting bored.

Osusaki Lighthouse

At Osu Hamlet 大須, which seemed more populated than the other fishing hamlets on this peninsula, we finally found a vending machine in front of a small grocery store. And once again, it turned out to be the last vending machine we would see until our goal point. (There is another store near Osu Fishery Port but we missed it.)

Several road signs in the hamlet pointed toward a lighthouse. We felt as if they were practically shouting, urging visitors to go see it, so we decided to stop there for a longer lunch break.

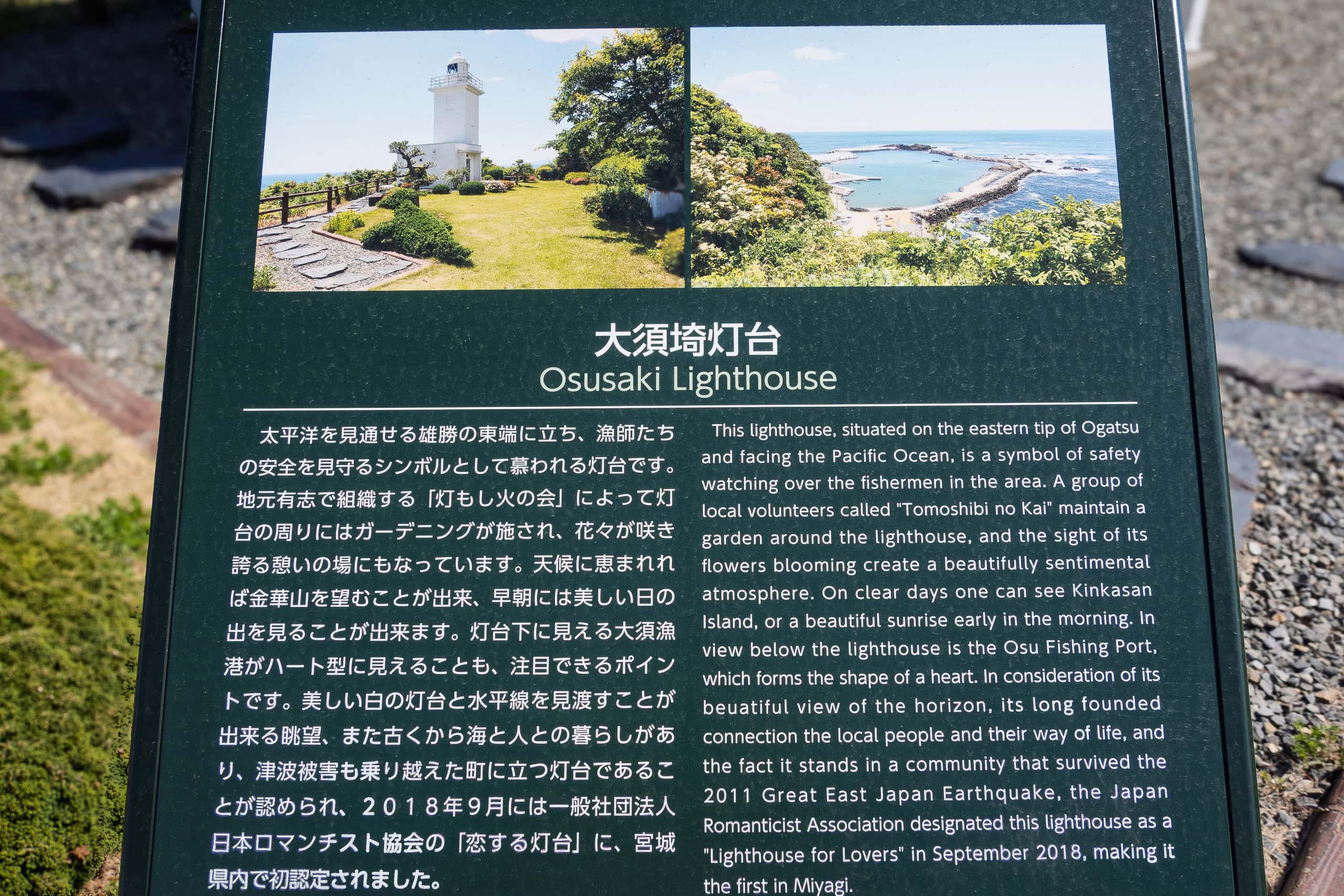

The Osusaki Lighthouse 大須埼灯台 itself didn’t look particularly remarkable — much like many other small lighthouses on the countless capes along the MCT route.

But we discovered it was popular for the view it offered over the fishing port below. From the hilltop, the wave-break walls formed the shape of a heart. That’s why it had become a well-known dating spot for young couples.

In fact, the view from a picnic table by the lighthouse was excellent. The flowerbeds around it weren’t in bloom yet, but we could tell the spot would be especially lovely during flower season.

The Japanese are famous among anime and comic fans worldwide for turning literally anything into anthropomorphic characters. (Ex: swords, tanks, battleships, racehorses, shrines, towns, hot springs…)

And of course, lighthouses are no exception.

To promote lighthouses and preserve their historical and cultural value, a public project selected notable lighthouses along Japan’s coasts and reimagined each of them as attractive young men.

Osusaki Lighthouse is one of only three along the MCT route to receive this honor.

The other two: Kinkasan Lighthouse in Miyagi and Rikuchu-Kurosaki Lighthouse in Iwate.

Down to the bottoms

After a long break at the lighthouse park, we returned to the road through Osu Hamlet, which of course dropped down to the lower part of the village (Osu Fishing Port) and then climbed back up to the no-view paved-road between woods again.

For a while the road ran through forest and then descended to another small beach.

There was absolutely nothing there. We knew a fishing hamlet had once stood here, but now all that remained was a vast empty space and a tiny fishery port — with no one in sight.

Soon the trail went uphill again, rejoining the same main road.

These repetitive ups and downs, forcing us through every single little beachside hamlet, became truly irritating.

We couldn’t understand why the route had to go down to those beaches, especially when there was literally nothing there. Having walked on paved roads most of the day, the endless trees had become monotonous and boring.

By now our spirits were low, almost hitting the bottom, and we were left only physically exhausted.

As we approached Ara-toge Pass 荒峠, the second highest point today, the route was supposed to drop down once again, this time to pass through yet another ordinary hamlet.

That was the moment our patience finally snapped.

“No. We’re not going down there for nothing.”

We skipped the hamlet and stayed on the main road, since the official route rejoined this very same road a short distance ahead anyway.

We knew these hamlets had been hard hit by the tsunami ten years ago, and that all the houses had been relocated to higher ground near the now-empty beaches.

We also knew the tiny ports and beaches were too small to justify rebuilding in the face of inevitable population decline.

But to walk down there just to see emptiness felt, honestly, depressing.

It had been two weeks since we started walking the MCT, and to be honest we still didn’t feel satisfied or fulfilled.

About 90% of the sections we had covered so far were on paved roads or forest dirt roads. Only a few mountain trails. We hadn’t seen much in the way of spectacular nature or breathtaking scenery yet.

We began to wonder if we should think of the MCT as purely a walking-training route, without expecting the joy of hiking.

We passed Ara Toge pass and kept walking toward today’s goal — just to finish the day.

In spring 2025, the Michinoku Trail Club announced the first major revision of the route. With new roads completed and the scenery altered after most of the reconstruction work, several sections now include minor changes or alternate routes.

The most significant change was in the Cape Funakoshi area of the Ogatsu Peninsula—the very part we skipped. It is now cautioned that the road we walked instead of the official route back in 2021 may no longer be passable today.

Onosaki Toge Pass

We finally reached the last fishing hamlet called Naburi before Onosaki Toge Pass 尾ノ崎峠, the long natural trail that crosses Mt. Myōjin 明神山.

Naburi port was also deserted, and the tiny strip of flat land between the mountains and the sea was completely enclosed by a long stretch of seawalls.

Tired of having our view blocked, we climbed up onto the wall. On top it turned out to be a pleasant walkway, with metal fences lining the edge, and from there we enjoyed a beautiful view of the sea. At the far end of the wall we could already see the mountain we would soon be crossing.

The trailhead for the Onosaki Toge Pass lay at the end of the hamlet.

The natural trail on this side of the mountain was messy. With the sun already dipping behind the peaks, the forest grew dark quickly. I would never want to enter a trail like this alone at such an hour — without Erik, I would have turned back.

As always, the route was well marked with MCT ribbons tied to tree branches. Still, some stretches were tough to push through, with thick layers of fallen leaves and scattered branches.

We pressed on, eager to reach our goal and just finish the day. Besides, we had to get there by 6 p.m., the time we had told the taxi company to meet us.

Once we crested the pass and began descending, the trail brightened again as the sun shone through. The downhill side was completely different — well maintained and easy to walk.

Perhaps the difference in tree species played a role, but whatever the reason, it felt far more welcoming.

As on many mountains, the descent seemed much longer than the climb. Maybe it was just our perception, but carefully inching down over the springy carpets of dried leaves, trying not to slip, certainly made it feel slower.

Lake Nagatsuraura

At last we emerged from the mountain trail and followed a paved road along Lake Nagatsuraura in the dusk.

After passing another small hamlet, we crossed a bridge over the narrow channel connecting the inland sea to the Pacific Ocean.

Then we had to figure out how to cross a huge construction zone with no recognizable pedestrian paths in order to reach the inside of the seawalls, where our goal and taxi pickup point — the Hamanasu Café はまなすカフェ — was located. In the end, the site was completely quiet, with no workers in sight, so we simply took the shortest path across.

We reached our goal just a few minutes before 6 p.m. Once again, the taxi was already waiting. We climbed in without even pausing for breath, leaving exploration of the area for tomorrow morning.

Twenty minutes later, after a smooth ride, we arrived at our hotel for the night.

We were completely exhausted today, both physically and mentally.

Fortunately, our hotel was right across from a large shopping complex with supermarkets, restaurants, and all kinds of stores.

That evening we comforted ourselves at a restaurant we had been determined to visit and looking forward to throughout the entire miserable walk today.

It had been a couple of weeks without it, and we were really missing it.

McDonald’s.

Day 16 – MCT

| Start | Michi-no-eki Ogatsu |

| Distance | 32.5 km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 1194 m/1202 m |

| Finish | Hamanasu Cafe |

| Time | 9 h 10 m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 254 m/ 0 m |

Route Data

The Michinoku Coastal Trail Thur-hike: late March − mid-May 2021

- The first and most reliable information source about MCT is the official website

- For updates on detours, route changes, and trail closures on the MCT route

- Get the MCT Official Hiking Map Books

- Download the route GPS data provided by MCT Trail Club

- MCT hiking challengers/alumni registration

Comments