The Only Way Is Up — Keep Walking

“If you hit rock bottom, you can only go up from there.”

Is it true? We would find out today.

Last evening, on the way to our hotel from Lake Nagatsuraura, we arranged this morning’s pickup with the taxi driver. So when we checked out of the hotel, the taxi was already waiting (again) and immediately drove us back to the Hamanasu Café, our goal point yesterday.

Our day began by walking through a vast, wide-open construction site. It didn’t even look like they were building anything new — more like they were just leveling the land.

The MCT route shown on the map was, of course, nowhere to be found on the scraped-flat ground, so we simply crossed straight through.

Beyond the construction site stretched another vast open plain. This time it was laid out in grids of future rice paddies, still bare and unplanted, the dark brown soil stretching as far as we could see. A couple of large farm tractors prowled idly across the fields

Although the official MCT route followed a long, straight car road cutting through the farmland, I didn’t want to keep walking on a paved sidewalk. Instead, I stepped onto the dirt farm tracks running along the edges of the paddies.

Erik, however, stayed on the sidewalk — he wanted to avoid the sharp pebbles that pressed through the soles of his shoes, which had worn thin after carrying his taller-than-average frame over so many long days.

We were on this straight road only because it crossed the large bridge over the Kitakami River 北上川. As always, the MCT route itself continued north along the Pacific coast. But since our starting point today, the Hamanasu Café by Lake Nagatsuraura, was near the river mouth, we first had to walk nearly 4 km west along the south bank to reach the nearest bridge.

Former Okawa Elementary School

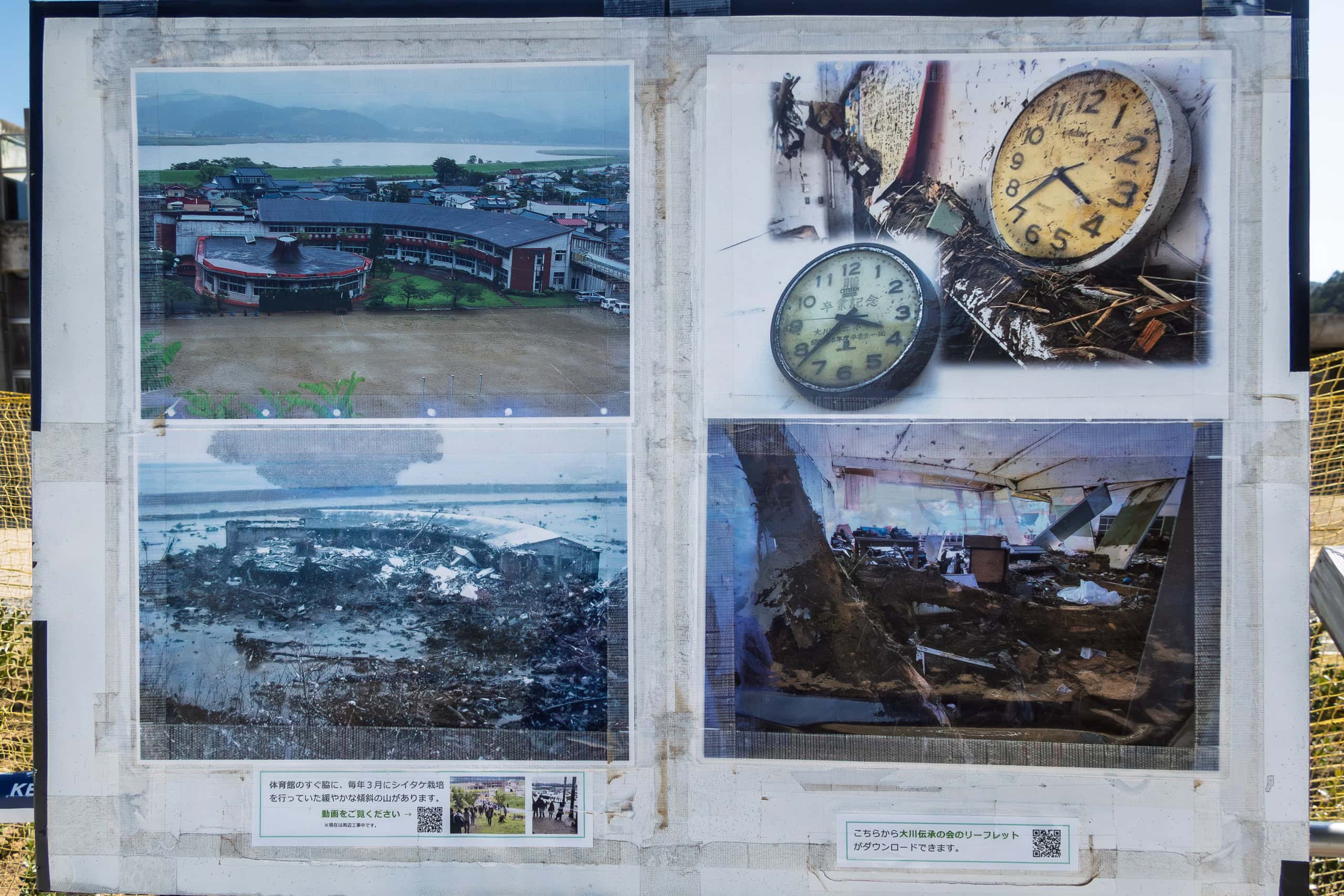

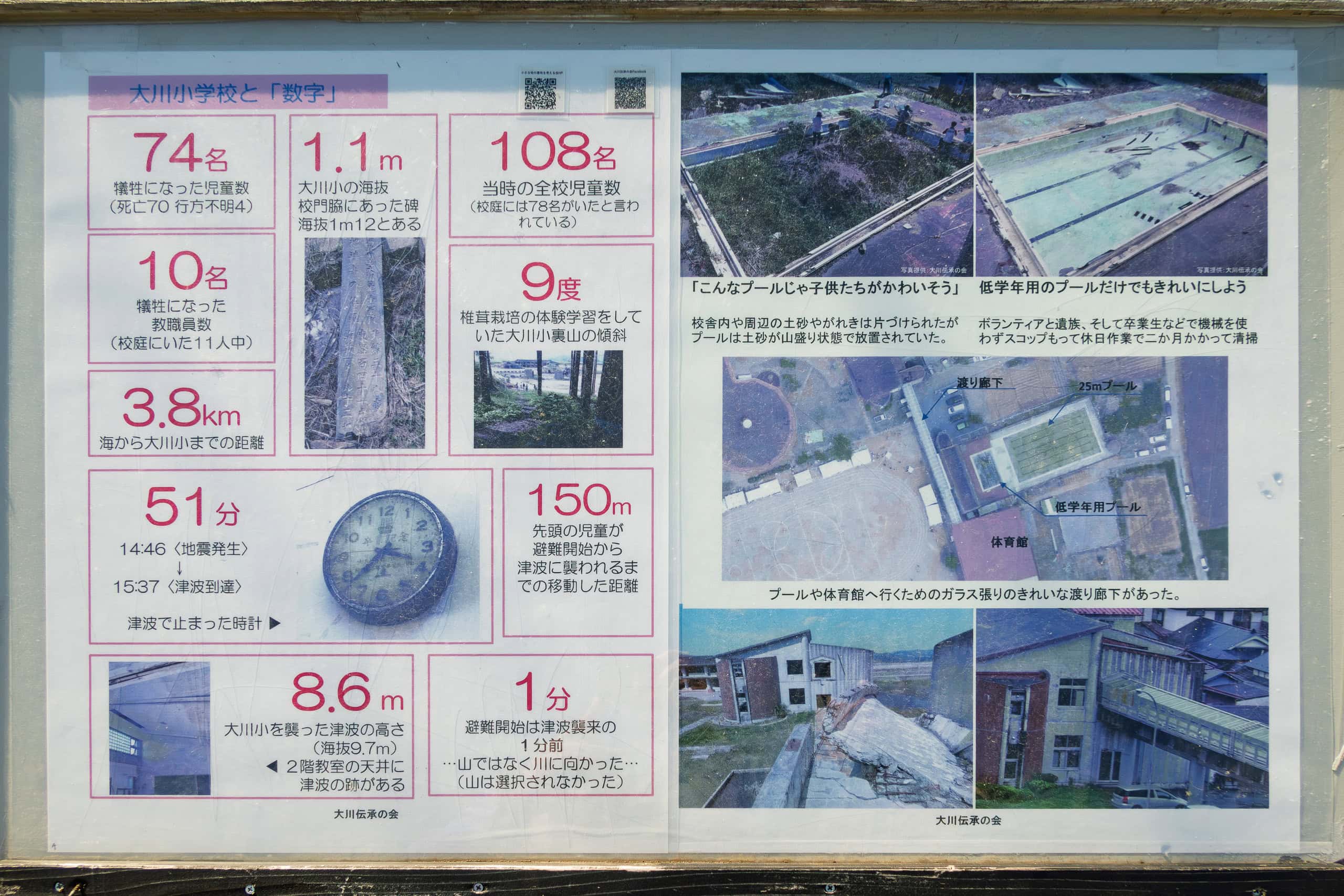

Eventually, the dark outlines of ruined buildings came into view far ahead of us. This was the site of the former Okawa Elementary School 旧大川小学校.

The massive earthquake and tsunami brought unimaginable agony and tragedy all along the Pacific coast of Tohoku. Every story of loss is equally heartbreaking, unforgettable, and full of lessons. Yet the name of this school — and what happened here that day — remains etched in memory as one of the most shocking and disturbing cases.

As is often true for schools in rural Japan, Okawa Elementary was small, with just over 100 students from first through sixth grade.

In a single moment, over 70 percent of them — 74 out of 108 — along with 10 teachers, were lost. It was the largest number of victims from a single school in the entire tsunami disaster.

The reasons behind this immense loss became deeply controversial.

The school stood beside the river, about 4 km inland from the Pacific coast. That meant there were about 50 minutes between the earthquake and the moment the tsunami surged up the river and struck the school grounds. Low mountains rose directly behind the school, but evacuation did not go that way. Instead, the children, led by teachers, moved toward a nearby bridge that stood slightly higher than the school itself.

Based on past large-scale tsunamis in local history, no one had expected the waves to reach as far as the school or the bridge. But they did, and everything was swept away.

Still, none of us who were not there in the midst of such an extraordinary, terrifying situation can ever say with certainty what was right or wrong.

Today, fences surround the fragile remains of the school buildings to keep visitors at a safe distance. The former school grounds and surrounding residential area have been turned into a large memorial park, and by April 2021 construction looked nearly finished.

A newly built museum stood behind us, though its interior was not yet ready for the public. In fact, we were just three months too early for its opening ceremony.

If we ever return to the MCT, this museum will certainly be on our must-visit list.

Crossing the Kitakami River

Right after leaving the school, we crossed the New Kitakami-Ohashi Bridge 新北上大橋 over the Kitakami River.

The river is very wide, and it took us a while just to get across. We enjoyed the calm, beautiful blue water and the refreshing sea breeze, but we didn’t yet realize that we were leaving the negativity behind us and about to discover a whole new side of the MCT.

Looking back now, crossing that bridge was a turning point in how we saw and felt the trail. From here, though we didn’t notice it at the time, we were entering “the northern part” — the sections of the MCT with more nature and scenic beauty.

Along the north riverbank runs the newly built, wide National Route 398. We were supposed to follow this road for most of the day.

For a short stretch after the bridge there was a good sidewalk, but to our shock, it suddenly ended at a random spot.

The riverside highway is long and straight, and on a sunny spring weekend many drivers and motorcyclists were clearly enjoying the chance to speed. We didn’t think it was safe to keep walking in the narrow strip between the white sideline and the guardrail (we had had enough of that already), so we climbed over the guardrail and took a dirt farm road running through the vast fields alongside Route 398.

We passed rows of large glass greenhouses like the ones commonly seen in the Netherlands — a sight that gave Erik a brief feeling of home. In fact, the name of the greenhouse farm was De Liefde. As you might expect, they grow bell peppers and tomatoes there using Dutch greenhouse techniques.

The farm road eventually rejoined the riverside highway, and to our relief, a proper sidewalk appeared again.

Just as we started feeling the need for a rest and a bathroom, we spotted a shrine across a small inland canal beside Route 398. Quite a few people were there, and as we entered from the parking lot, more cars arrived.

The shrine building and office looked fairly new, and much of the grounds felt unnaturally flat and empty. Considering the location, it was easy to imagine that the lower part of the shrine had been washed away by the tsunami.

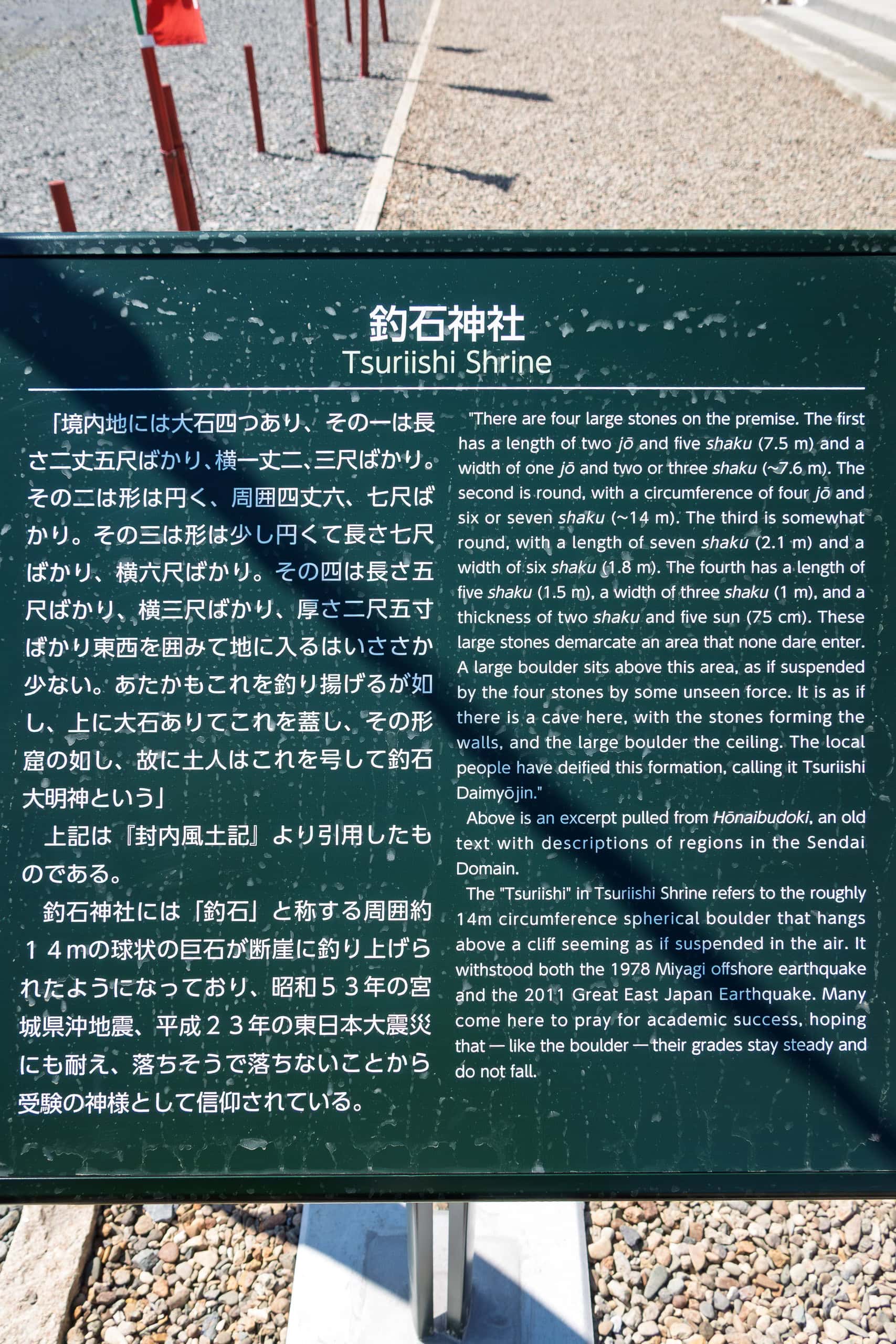

But the true heart of the shrine was not in the lower ground. The deity is enshrined at the top of a small hill, and the most famous sacred object — the one that gives the shrine its name, Tsuriishi Jinja 釣石神社 — is a giant rock jutting sideways from the hill.

Seen from the front, it looks as if an invisible rope is holding it in place.

This sacred rock has endured countless earthquakes, including the Great East Japan Earthquake ten years ago. It never falls.

For that reason, people — especially students and their parents — admire it and come here from all over Japan to pray for success in entrance exams. In Japanese, “to fail an exam” is literally “to fall,” so something that never falls is considered the perfect good-luck charm.

The fact that the rock looks like it could topple at any moment makes it even more inspiring for students on the brink.

Because the Japanese school year begins in April, entrance exams had already finished by the time we visited. The visitors with us that day were probably praying for other kinds of challenges, or perhaps they were well-prepared students aiming for the next winter exam season.

In the middle of the shrine grounds stood a small snack shop selling drinks, sandwiches, and fried chicken.

This stall — Karaage (fried chicken) Coccoya 唐揚げ こっこ屋, run by a warm, grandmotherly cook — is popular with locals and has even appeared on national TV.

Many MCT hikers stop here for a welcome break.

Sadly, because of COVID, it was closed when we visited. Otherwise I would never have missed the chance for fried chicken, especially since there was a chance we would see no convenience stores or other food shops anywhere along Route 398 for the distance we would walk that day.

As we were leaving the shrine, another car pulled up and a group of women in workout clothes jumped out.

They were excited, laughing and cheering as they rushed to take pictures of the rock and everything around the shrine. It made us smile.

Their pure joy and energy seemed to symbolize the cheerful spring atmosphere that filled every corner of the shrine that day.

The First Encounter

National Route 398 eventually reached the mouth of the Kitakami River and continued along the Pacific coastline, passing through tunnels here and there.

Strangely enough, the more tunnels we went through, the better things seemed to get. The Kitakami River bridge had been the turning point, and now these tunnels felt like gateways to a brighter chapter of our MCT thru-hike.

For the first time since the vending machine at the giant rock shrine, we spotted another one — this time in front of the entrance to Shirahama Swimming Beach 白浜海水浴場, just before the first tunnel. And then another after the tunnel.

In fact, when it came to water supply, today’s section turned out to be a vending machine paradise. Unlike yesterday, when we could find only a few machines along the whole route and they were spaced kilometers apart, today we saw one almost every kilometer.

At one spot, we even found four machines lined up together!

At Shirahama Beach, young families were enjoying BBQs under the spring blue sky. A pair of young people were busy turning a small white cottage into a food stand or shop at the edge of the picnic park.

Cars passed us from both directions, but unlike the last few days with noisy construction trucks, we didn’t feel annoyed. These cars belonged to people out enjoying their weekend, and their presence gave the area a lively, vibrant energy.

It was uplifting to see families having fun on a sunny weekend instead of deserted beaches and silent hamlets.

And yes, vending machine paradise.

We have to admit: our happiness on long-distance hikes in Japan really depends on how easily we can access vending machines along the way.

Wildflowers bloomed here and there, and many roadside houses had lovely flower gardens. Occasionally, Route 398 opened up to reveal beautiful views of the sea. Around an observation hut, cherry trees were in full bloom.

We breathed in the sweet spring air and enjoyed walking — even on a paved highway. Then, at the edge of our vision, we noticed something standing halfway up a grassy hill.

So suddenly, so unexpectedly — just standing there.

The serow stared at us. We stared back. For a moment, we all froze in silence.

This wasn’t our first time seeing wild Japanese serows. Back home in rural Shikoku, which is also their habitat, we had occasionally spotted them while driving our tiny car through remote mountain roads. Usually they were calm and didn’t rush to run away.

Since they are an officially protected species in Japan, they cannot be hunted or harmed. Unlike most wild animals, decades of protection seem to have made them lose their fear of humans. Instead, these curious creatures often stand their ground and gaze back at us.

In Tohoku, they seemed even more relaxed — so much so that one could be found standing casually by the roadside of a busy highway.

After studying us with its large black eyes for a few minutes, the serow seemed to lose interest, turned away, and slowly walked up the hill until it disappeared into the bushes.

This was our first encounter with Japanese serows along the MCT. In fact, it was only the first of many.

Cape Kamiwarizaki

Soon after our first encounter with the serow, the MCT route left Route 398 and followed a side road to Cape Kamiwarizaki 神割崎.

Cape Kamiwarisaki is clearly a popular weekend destination. We passed families and groups of motorcyclists in the parking lot before walking down the path and flight of stairs to where ocean waves crashed dramatically through the narrow crack that splits a cliff in two.

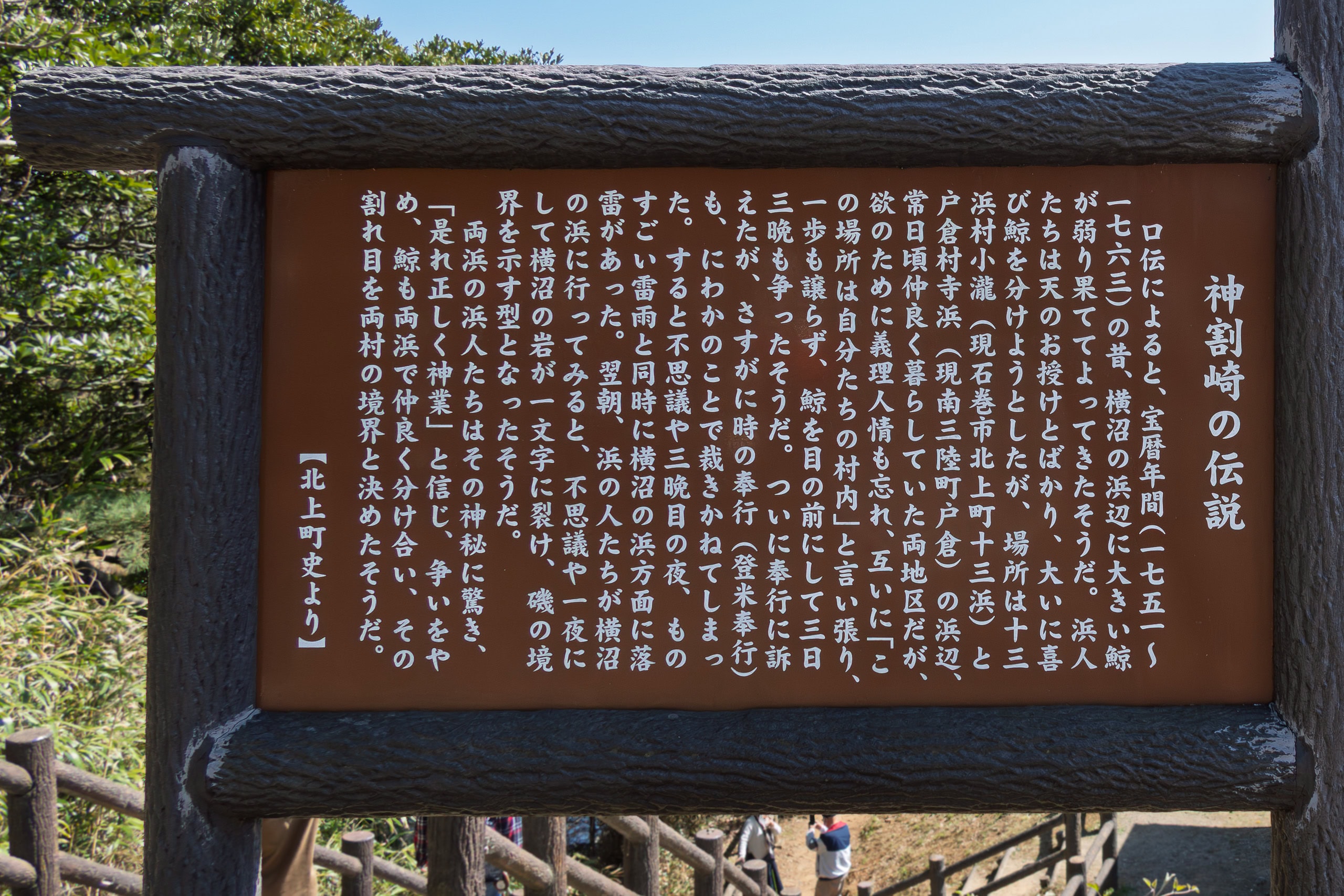

At the entrance, an information board explained the origin of the cape’s name. It was a strange story — and I really wished there had been an English version for international visitors.

I quickly translated it for Erik:

Around the mid-18th century, a dying whale washed ashore at the border of two fishing hamlets. The people of both villages, forgetting their history of friendship and cooperation, began fighting over whose territory it had landed in (and thus who had the rights to it).

For three days they argued, until they brought the case before the local magistrate. Even he found it difficult to judge.

On the third night, a fierce storm struck, and lightning hit the beach. The next morning, the villagers found that a great cliff had been split in two, the crack marking the border between the hamlets.

Awestruck by this divine judgment, the villagers made peace and shared the whale together.

(Kamiwarizaki 神割崎: kami 神 = god, wari 割 = split, zaki 崎 = cape)

From the indescribable look on his face, Erik didn’t seem especially impressed by the story — but he definitely enjoyed the powerful waves at Kamiwarizaki.

And even today, the “judgment of the gods” still stands: Cape Kamiwarizaki marks the municipal border, where we said farewell to Ishinomaki City after many long days.

The next municipality, Minamisanriku Town 南三陸町, manages most of Kamiwarizaki Park, including Kamiwarizaki Campfield 神割崎キャンプ場.

The campground is huge, with tent sites, log cabins, and auto-camping areas. When we visited, all campsites were temporarily closed due to COVID. Since we hadn’t planned to camp anyway, we didn’t explore the facilities.

What we really needed was the administration building, which supposedly had a café and shop. Still, we tried not to get our hopes up — in COVID times, anything might be closed or operating at minimum capacity.

To our delight, it was open. Even better, we arrived just before 2 p.m., the last order time. The café staff welcomed us warmly and assured us it was no problem to prepare lunch.

All the dishes and finger foods were made with locally grown vegetables and seafood fresh from nearby ports. We were especially intrigued by their “Cape Kamiwarizaki Curry,” styled to look like the cape itself.

When I asked about ordering a double-size portion to share, the server warned us it was “super big.” Thinking twice, I ordered a single curry for myself and pancakes for Erik. When the plates arrived, we were grateful for her advice — even the single portion curry was huge.

What impressed us most was the pride they took in using local specialties for every dish. Even the desserts were no exception.

The ice cream came in three flavors: seaweed, octopus & miso, and sea pineapple (hoya in Japanese).

No vanilla, no strawberry, nothing ordinary — just seafood flavors.

But sea pineapple? I had never even eaten the real thing, so I had no idea what it would taste like.

All three flavors tempted me equally. (Erik gave up immediately — for him, seafood ice cream was a step too far!) But of course, I chose the one you’re all thinking of.

Sea pineapple ice cream was surprisingly delicious, while still carrying the distinct flavor and scent of the sea.

(As of 2025, the flavor has been replaced by whale ice cream. I love their dedication to originality.)

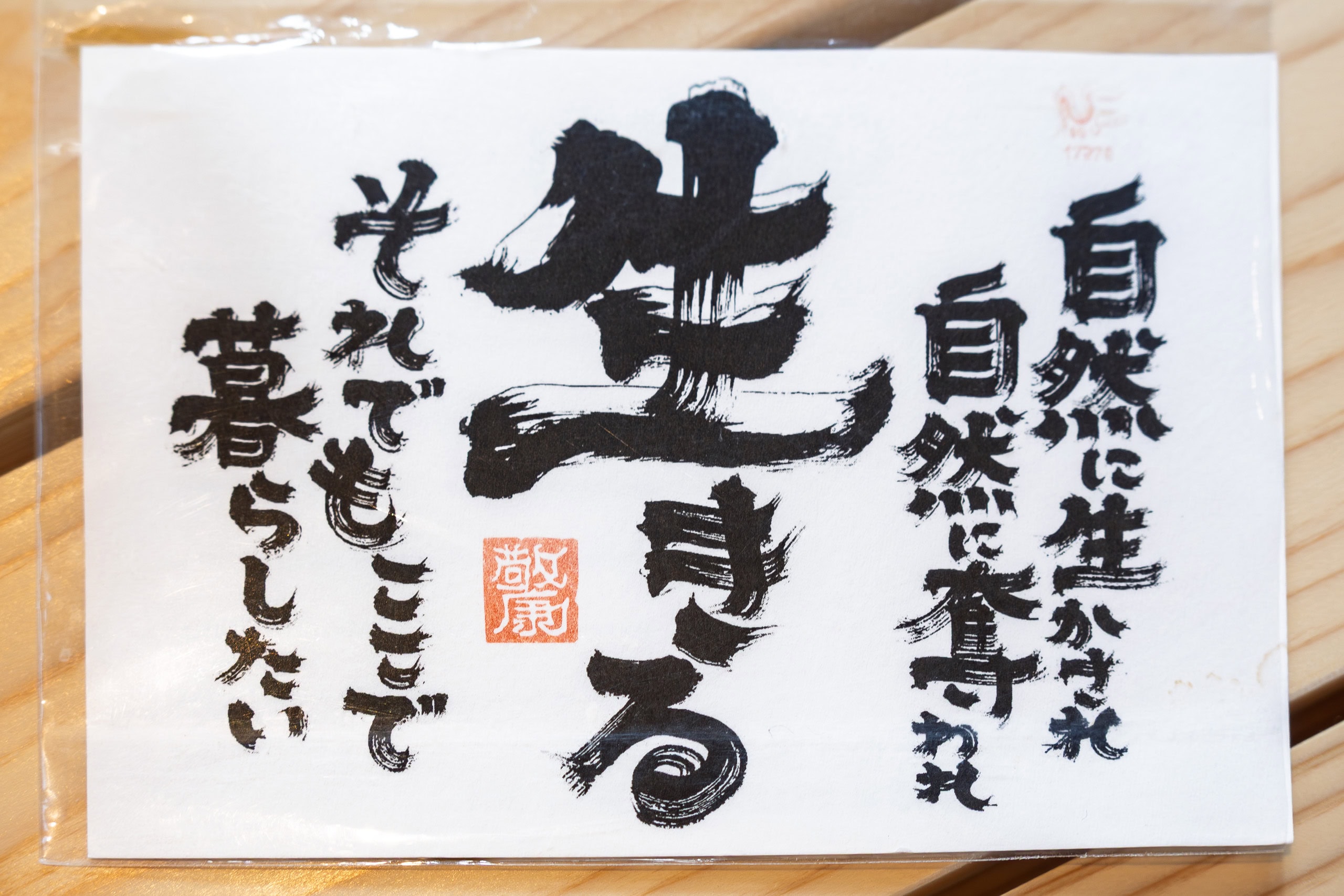

On our table, a card with Japanese calligraphy was displayed. In bold letters it read: 生きる (to live). On either side of it was written:

“Nature gives us life. Nature takes it away. Still, we will live here.”

I really liked those words — they captured the exact atmosphere of this area: the energy of reconstruction.

The administration building also had a corner filled with rental camping gear, BBQ equipment, cooking tools, and more. The shop sold food, drinks (including alcohol), charcoal, and daily necessities.

In short, people could show up with nothing and still enjoy camping.

No wonder this campsite is so popular among MCT hikers — even the official website has a page dedicated to detailed information for those walking the trail.

Hamlets of Togura

After a long, satisfying lunch, feeling full, we left the campfield and began exploring Minamisanriku Town.

The MCT route followed Route 398 along the Togura District 戸倉地区, often diverting onto smaller side roads through seaside hamlets.

This time, each hamlet showed visible signs of life and carried a much more active vibe.

The houses looked large, tidy, and well-maintained. Many had flowers planted in front yards, and vegetable gardens flourishing beside them. We were especially happy to see residents outside, tending their gardens or working with fishing equipment.

After so many days of rarely seeing locals outdoors, it was refreshing — it added warmth and meaning to the views as we walked. This area felt alive.

Not long after leaving the campfield, we entered the first hamlet, Fujihama 藤浜.

A small truck in front of us was creeping along at an oddly slow pace. When we finally caught up and passed, the truck stopped. An elderly man leaned his head out of the driver’s window and called to us: “Where are you from? Which way are you going?”

Apparently, he had spotted us walking Route 398, and his curiosity about two strangers — especially one super-tall foreigner — overcame his usual shyness.

Right in front of where we stopped was a new-looking shrine. Beside its torii gate stood an old stone monument.

Carved into its front were the words: “When an earthquake happens, immediately watch out for the tsunami.”

The date inscribed was March 3, 1933. After the great earthquake and tsunami of that year, the survivors of the hamlet erected the monument to pass this lesson on to future generations.

The man told us that one of his relatives had rebuilt the shrine just the previous year.

When I asked about the March 2011 tsunami in this hamlet, he pointed to a storage shed on higher ground across the road. “It used to stand farther back, on higher land,” he said. “The massive wave lifted it up and carried it here.”

He then pointed to a corner of the port, where fishing nets and buoys were piled high. “My house was there. It was all washed away. Now we live in a new home in the higher residential area behind that hill.”

We realized we had heard far more from him than he had asked about us. Deep down, his true desire may not have been to pry into strangers’ lives, but to share his story — the story of his hamlet and his home on that tragic day.

After passing a few more hamlets, we arrived at the Minamisanriku Marine Visitor Center 南三陸 海のビジターセンター. The Michinoku Trail Club, which manages the MCT, operates six satellite information centers, and this was our second one after the main center in Natori.

Inside, it was as quiet as we expected. Displays focused on sea creatures and local nature, with some graphic charts and maps about the trail itself.

If we had called, someone would have come out to assist, but since we had no questions or needs, we simply used the bathroom and left quietly.

Eventually we reached the once-busiest part of the district, near Rikuzen-Togura Station.

A long stretch of high concrete seawalls sealed off the shore and flatlands behind, giving the impression of a prison wall.

According to the official mapbook, the MCT route followed Route 398 behind the walls, but instead we climbed up and walked along the top. It saved us a little distance, and the sea breeze in the sunset was far cooler and more pleasant.

The day’s plan had been 30 km, but by the time we arrived at our destination, we had walked nearly 35 km. Yet we didn’t feel as exhausted — physically or mentally — as we had yesterday.

Probably because we had good resting points along the way. The lively atmosphere, encounters with locals, and even a wild animal all contributed to keeping our spirits positive.

We passed the point where the MCT would leave Route 398 for the mountains, and continued on the last stretch to our hotel. It added only a few hundred extra meters, and we knew we’d return here tomorrow.

I had chosen Minamisanriku Hotel Kanyo 南三陸 ホテル観洋 not just for its location, but for its reputation for hot springs — especially the outdoor baths with ocean views.

By the time we checked in, it was already growing dark, so I soaked in the bath that night, and again the next morning, to savor the spectacular sight of the open ocean and the sunrise right in front of the steaming outdoor bath.

It was a good hike today, even though there wasn’t a single natural-surface trail and we walked on pavement the entire time. Still, we felt uplifted, carried by the positive energy of the area.

Hitting rock bottom was already behind us — and now we had begun to believe that things would only get better.

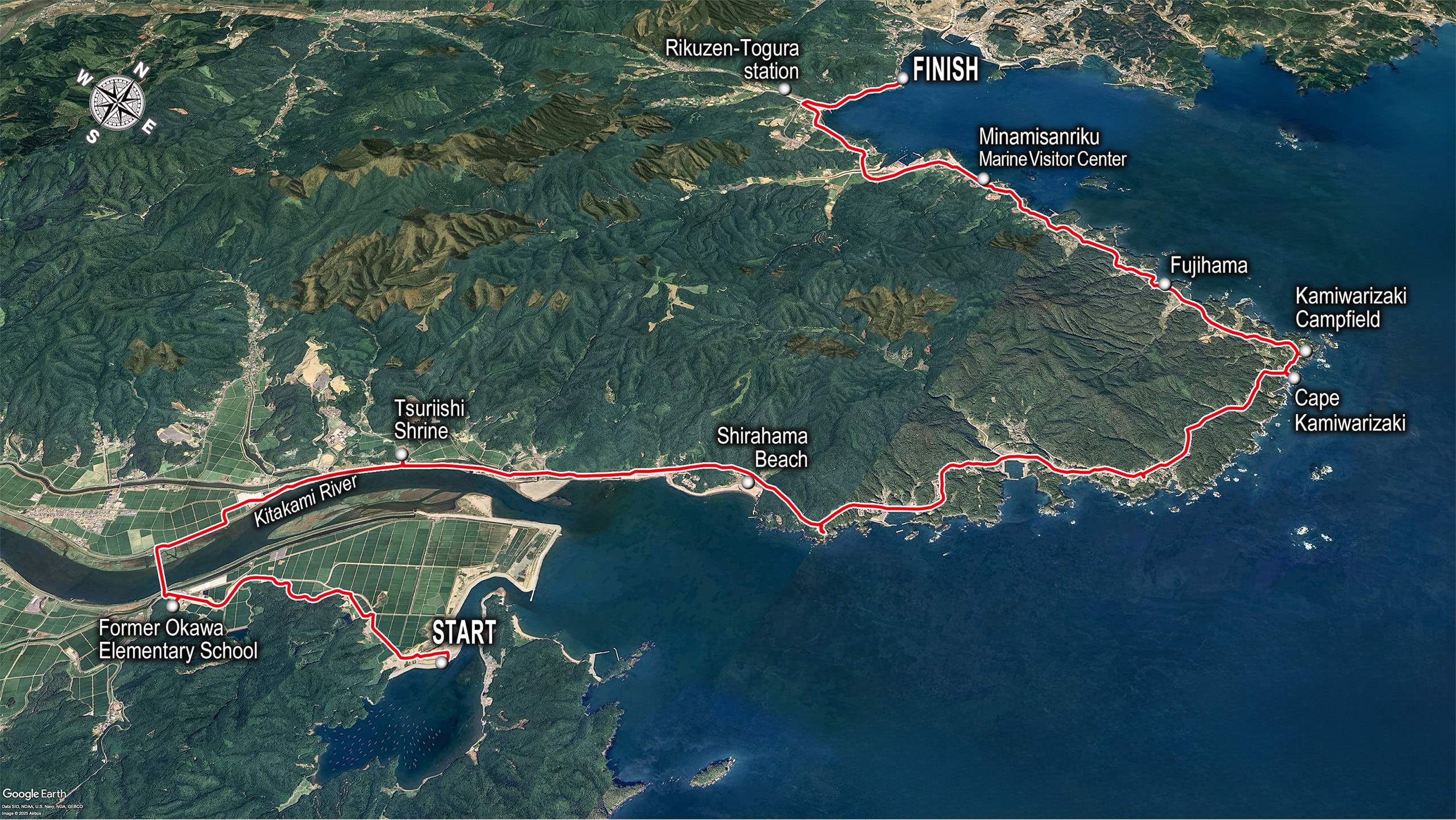

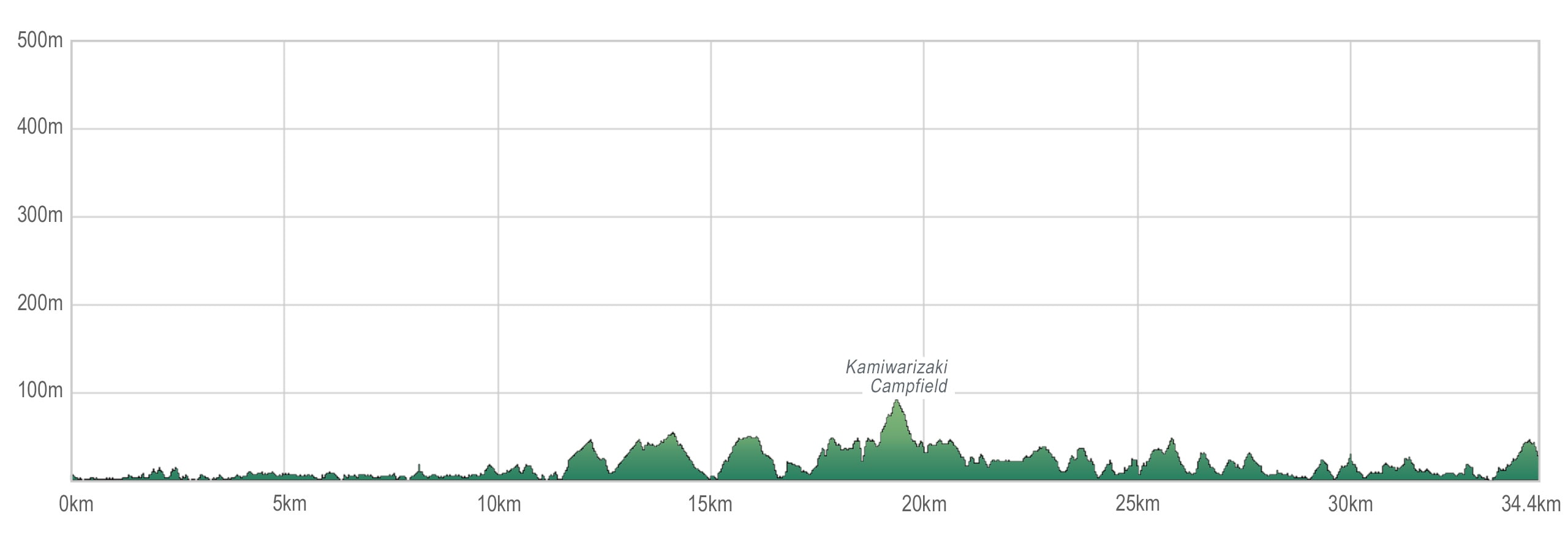

Day 17 – MCT

| Start | Hamanasu Cafe |

| Distance | 34.4 km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 569 m/535 m |

| Finish | Hotel Kanyo |

| Time | 10 h 5 m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 87 m/0 m |

Route Data

The Michinoku Coastal Trail Thur-hike: late March − mid-May 2021

- The first and most reliable information source about MCT is the official website

- For updates on detours, route changes, and trail closures on the MCT route

- Get the MCT Official Hiking Map Books

- Download the route GPS data provided by MCT Trail Club

- MCT hiking challengers/alumni registration

Comments