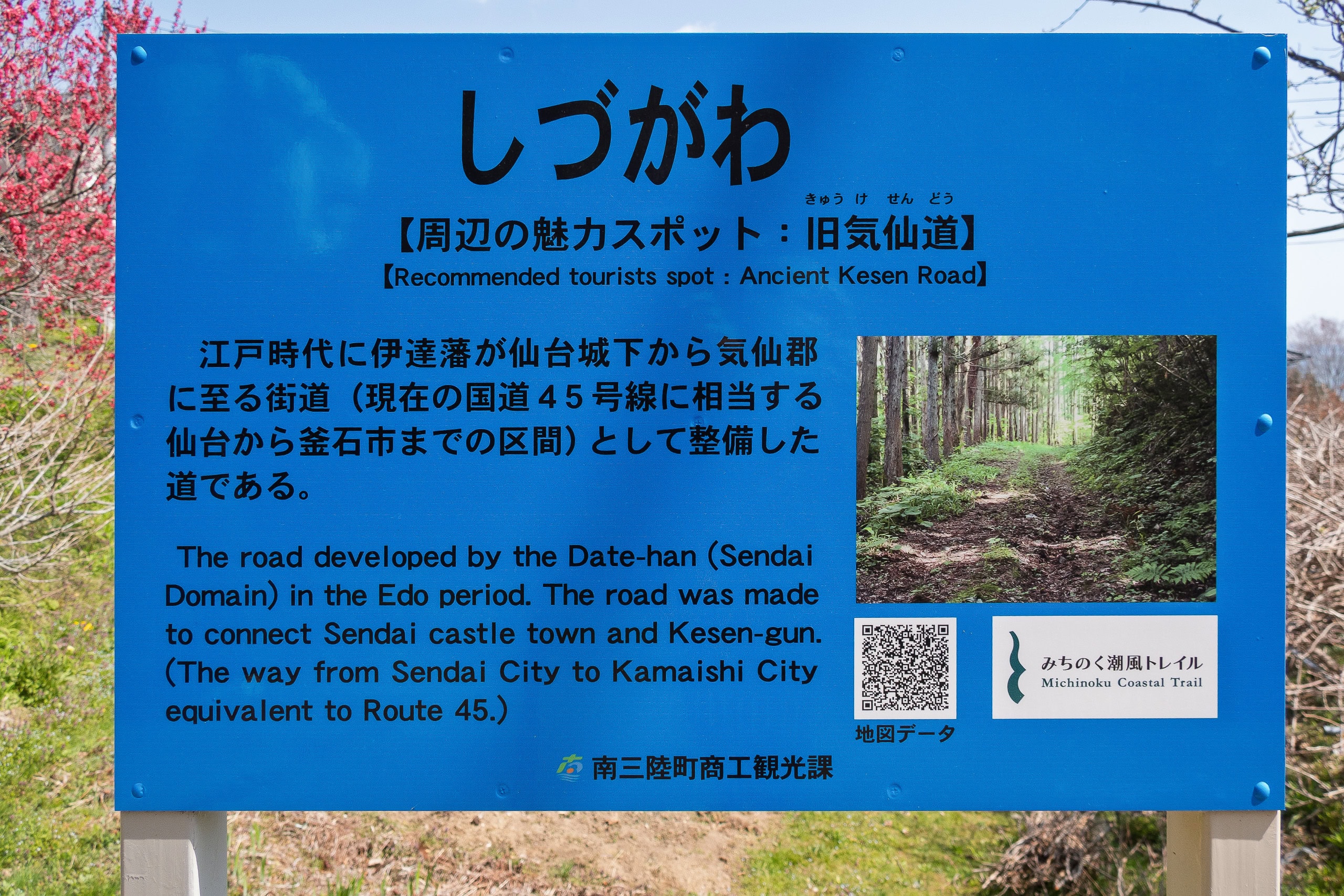

Historic Kesen-do Trail

Key words for today’s MCT route: octopus and Moai.

Moai means exactly what you think — the mysterious stone figures standing on Easter Island.

After a good, restorative night and refreshing morning hot spring and breakfast buffet, at Minamisanriku Hotel Kanyo, we walked a few hundred meters along the coastal highway (Routes 398 and 45 share the same road here) to rejoin the MCT.

From the point where the trail branched off from the highway, our MCT Day 18 hike began.

The route immediately passed under a BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) line and followed a narrower village road.

We walked through a quiet hamlet of only a handful of houses along a gentle incline, and soon stepped into a forest trail.

This trail is part of the historic Former Kesen-do 旧気仙道, once the main route between Sendai and the Kesen area.

Today, most of it lies buried beneath Route 45 and the Sanriku Expressway. The MCT makes use of the untouched remnants that still wind through mountains and forests.

It was a wonderful way to start the day: a quiet morning forest trail with only the relaxing chorus of frogs calling somewhere from a marshy hollow.

I noticed that many bare tree branches now carried fresh leaf buds. With every step forward from the MCT southern terminus, the scenery grew greener.

Walking through the bright spring growth gave our hike on the MCT a completely different feeling compared to the early days of dried grass, bare trees, and dirt-filled farmland.

The old unpaved trail was short — only a kilometer or two — but still rewarding after a full day of paved roads yesterday.

Soon we emerged by a few scattered houses and rejoined the coastal Route 398/45.

For the entire day, the MCT would remain within Minamisanriku Town: first heading toward the former town center by Shizugawa Bay 志津川湾, and later exploring inland through mountain villages.

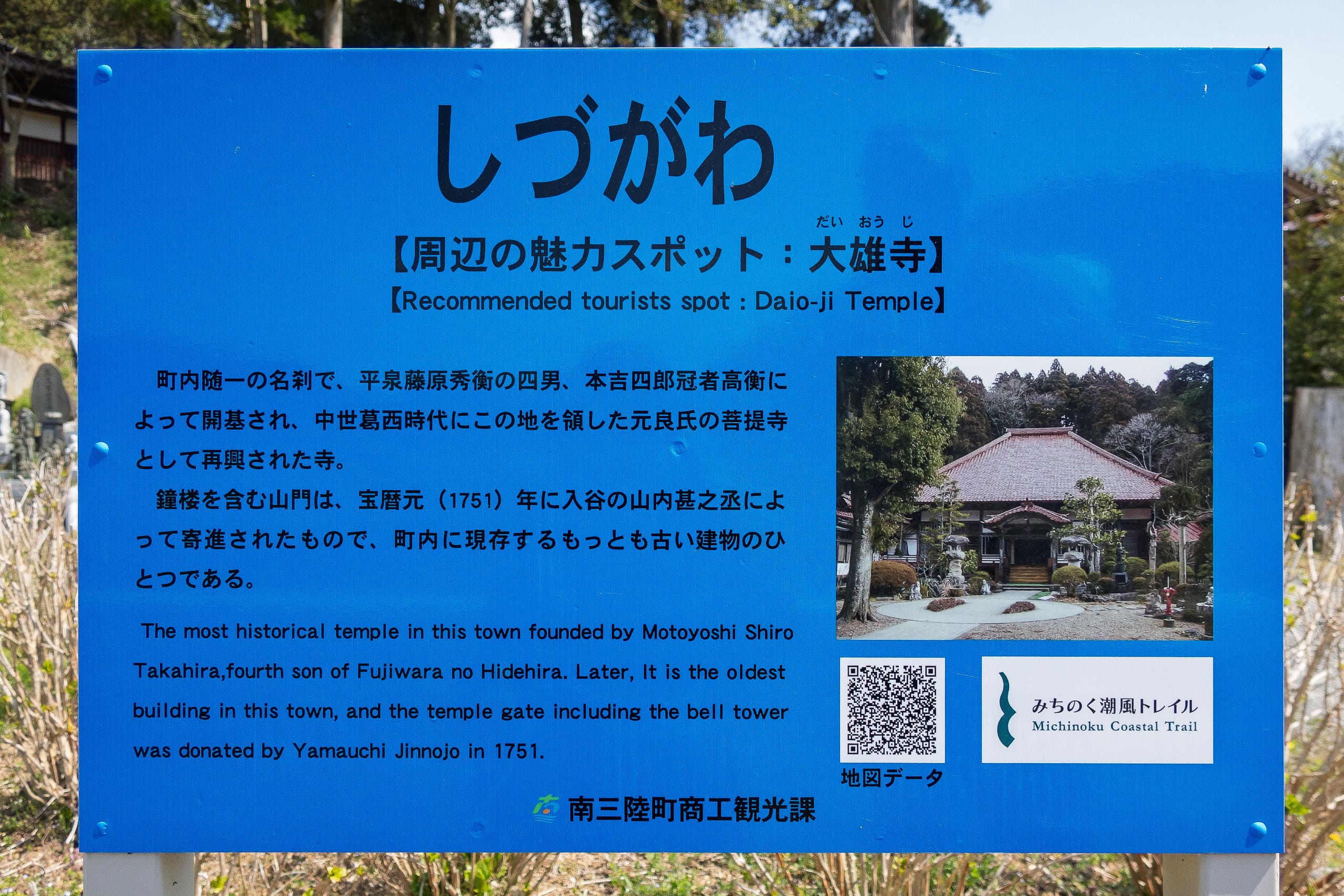

Shizugawa: Stories of Survival and Loss

As we approached the former town center of Shizugawa 志津川, we began to see large-scale construction underway across the vast flatland between two river mouths.

In the middle of this open space stood a half-destroyed four-story building. It wasn’t waiting to be demolished. Instead, the people in Minamisanriku had chosen to preserve it as a tsunami monument.

Unlike many of the ruins we had seen so far, this building — Takano Kaikan 高野会館 — was remembered not for tragedy, but for survival.

Takano Kaikan was an event hall, built solidly enough to also serve as a designated evacuation site.

On the day of the earthquake, ten years earlier, hundreds of local elders (average age 80) happened to be there for a performing arts festival. When the shaking stopped, many panicked and tried to flee outside.

But the venue staff, sensing the tsunami, stopped them: “If you want to survive, stay here!” They guided everyone up to the rooftop.

The waves that followed reached 17 meters high, destroying the town center and taking hundreds of lives.

But the Takano Kaikan staff had known this was the sturdiest building in town, and its rooftop stood just above the highest wave. Despite the building’s vulnerable location near the river mouths, luck — and foresight — saved them.

In the end, all 327 people, including the eldery festival participants, nearby residents, hotel staff, and even two dogs, survived on the rooftop of Takano Kaikan until they were rescued.

Although the core functions of the town have since been relocated and rebuilt on higher ground, Shizugawa has not been abandoned. New houses and shops now stand between empty lots. We picked up lunch and snacks at a 7-Eleven, then followed the MCT route across the street to the Sun Sun Shopping Village さんさん商店街.

San San Market reminded us of our favorite shopping complex in Onagawa, only smaller. One of the tenants was another convenience store — to Erik’s delight, it carried his favorite hot milk tea, which 7-Eleven hadn’t.

It was around noon, so visitors gathered in front of restaurants deciding where to eat.

We grabbed an outdoor table in the sunny corridor for a short break, and we treated ourselves to soft serve on iced coffee (for me) and premier soft serve (for Erik) from a café’s takeout window.

At the corner of the market, a large Moai statue stood — completely out of place.

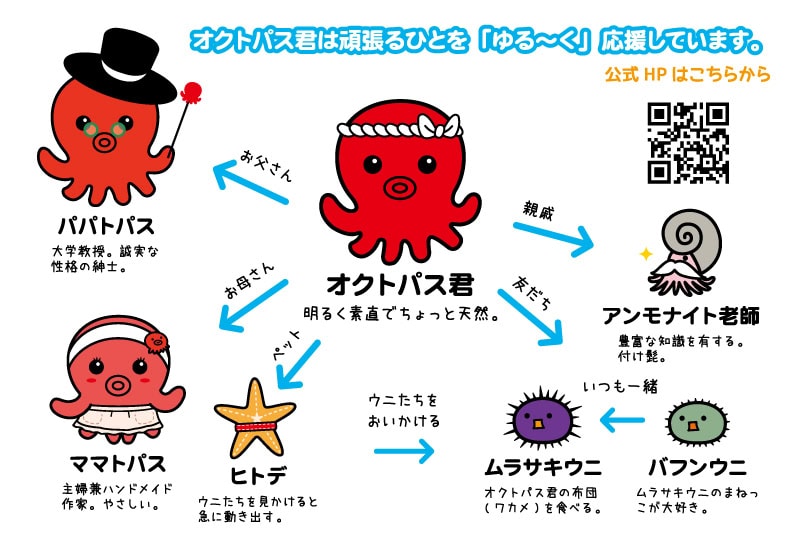

Apparently, Minamisanriku promotes its tourism with two mascots: octopus and Moai.

We had already noticed the octopus theme at the Kamiwarisaki campfield café yesterday.

But Moai? We had no idea.

But, as we continued walking, we kept spotting Moai-themed things scattered around town.

While the new town center and housing had moved to higher ground inland, the low flatland of the former town center was being developed into a memorial park.

But Takano Kaikan itself is not part of the park; it is privately owned by the same company that operates Hotel Kanyo, which has preserved it.

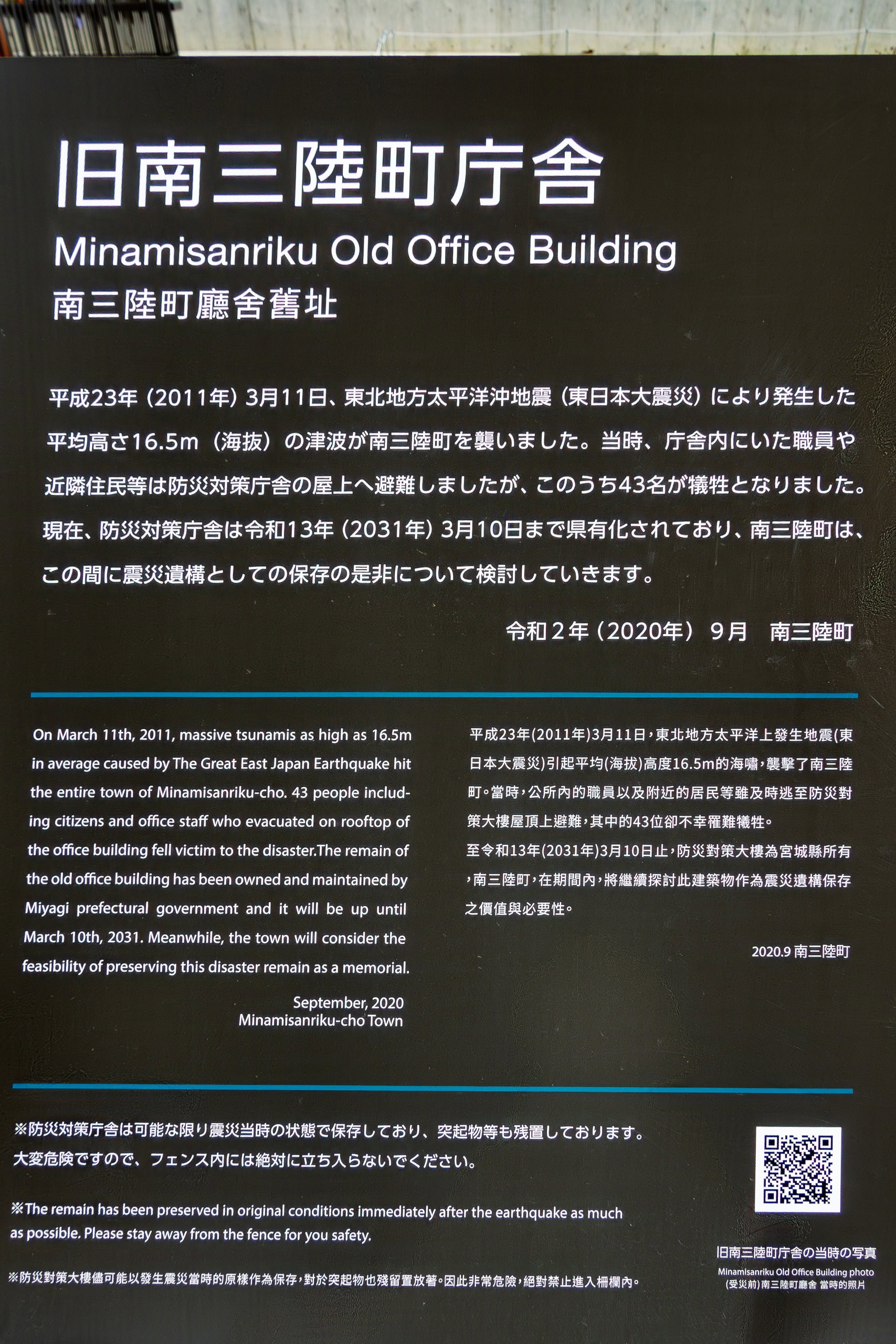

The park also includes a monument symbolizing not survival, but loss: the skeletal red steel frame of a three-story town hall building. What happened here that day was one of the most widely discussed tragedies of the tsunami, alongside the story of Okawa Elementary School.

This building had once housed the town’s disaster response center.

When the earthquake struck, many staff, including the mayor, gathered there. As the massive black waves approached, they evacuated to the rooftop — just as the people at Takano Kaikan had done. But this time, fate was cruel. The wave rose two meters higher than the rooftop.

Of the 53 people on the roof, only ten survived by clinging desperately to antenna poles and staircase railings. The other 43 were swept away. Among them was a young female staff member who, for thirty minutes after the quake, had shouted 62 announcements over the emergency broadcast system urging residents to evacuate. She continued until the very last seconds before the wave struck. She had just recently married and was preparing for her wedding ceremony.

The survivors on both rooftops endured a freezing, snowy night, soaked from head to toe, before being rescued the next day.

The mayor also survived on the town hall roof. He went on to lead Minamisanriku’s recovery for nearly 15 years. Today, as he prepares to retire in October 2025, he says he finally feels his mission is complete.

When we visited in spring 2021, the memorial park’s new building was still under construction. As a result, we missed the Minamisanriku 311 Memorial Museum, which opened next to the Sun Sun Shopping Village in 2022. Since then, it has welcomed more than 300,000 visitors.

Our Second Serow encounter

After crossing the memorial park, the route began heading inland along a one-lane road.

The “vending machine paradise” continued today — every so often we saw one, even as the area grew less populated.

In the former town center we had seen almost no MCT signposts. The first one appeared much later, at the corner where we left the road and turned onto a narrow path. Oddly, this post had no plates showing distance or destination. It just stood there silently. At least it pointed in the right direction, which was good enough for us. (Today, the plates are attached, so no worries.)

The narrow path quickly turned into a dirt forest road between farmland and woods. The weather was sunny and mild — perfect walking conditions. We were relaxed, turning a bend in the trail when suddenly —

Another Japanese serow.

It was standing right in the middle of the road, only a few meters ahead of us.

We froze, caught completely off guard.

Why are the serows here always so carefree, standing in the open as if it’s the most natural thing?

This one, too, simply gazed at us.

We didn’t want to scare him, but he was directly in our way. So we approached slowly. Even when we got quite close, he didn’t move until finally turning and hopping into the forest beside the road.

Inside the trees he quickly relaxed again, lingering nearby instead of fleeing further.

“You should have a little more survival instinct — you’re still supposed to be a wild animal,” I gave him a friendly reminder as we passed, while he continued to watch us from behind the trees.

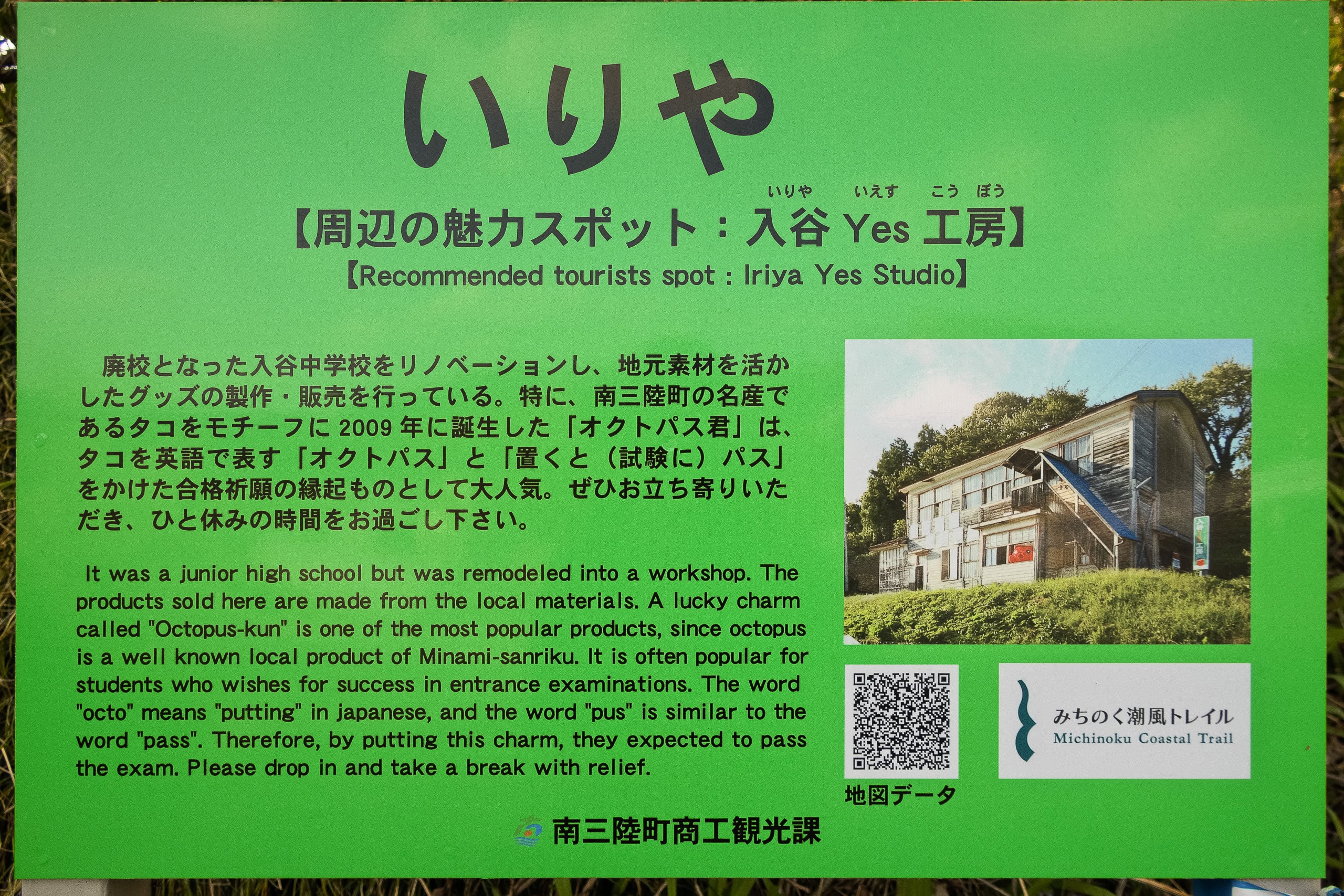

Eventually the forest road merged into a village lane that crossed Route 398. For the rest of the day we walked through the rural farming area of Iriya 入谷.

Iriya was a quiet, peaceful, and very pretty village.

At a small old shrine, the two guardian dog statues were so tiny they looked almost like pugs.

Everywhere in the village felt like a picture postcard of your dream rural Japan: fields, trees, even the wild plants seemed all beautifully cared for.

After days of walking through empty farmland, construction zones, and disaster-scarred coastal areas, Iriya felt like a gift. It reminded us that beauty on the trail isn’t only in dramatic coastlines or mountain views, but also in the harmony of people, nature, and daily life in a small rural village.

The Lucky Octopus

We walked along a narrow unpaved farm road through plowed fields, some already planted. The MCT route led us toward a small hill covered with dense trees at the center of a hamlet. We knew there was a shrine at the top, though the woods hid it from view.

At the base of the steep stone staircase to the shrine stood an old building with a big, cute octopus character on its sign.

Inside, the shop was overflowing with octopus-themed items. A wide variety of goods and foods were either shaped like octopuses or packaged with the character.

The staff explained that they were the designers and creators of these products, and that their work helped support the recovery of Minamisanriku Town.

The old building had once been part of a junior high school that is now permanently closed.

After the tsunami in March 2011 destroyed more than 70 percent of Minamisanriku’s homes, this inland village of Iriya was the only area in town with little damage.

Survivors from across town gathered here and asked themselves what they could do to help, especially for those who had lost loved ones, homes, and jobs.

Since the Shizugawa fishing port — once the town’s center — had long been known for its octopus catch, a cute octopus character had already been used in promotions before the disaster.

Building on that, they formed an organization to create jobs and community by making octopus-themed products. It was a small self-help project, but they believed it would give people hope and strength to stand again.

The store we visited was called YES Factory 南三陸YES工房, the main hub of their activities.

One of its most popular items is a palm-sized model of the octopus, especially valued as a charm for students and their parents before entrance exams…

Sound familiar? We immediately thought back to the giant “never-falling” rock at Tsuriishi Jinja Shrine we had visited the day before.

There, the hanging stone was lucky because it never falls. So why an octopus?

In Japanese, the word “octopus” can be heard as “oku-to-pass.” Oku-to means “to place on something,” and “pass” is borrowed from English. Together, it means “place it and pass the exam.”

Students buy the little octopus figures and place them on their desks, hoping they’ll help them succeed. And truly, no one laughs about exam charms in Japan — competition is serious.

The shop even had a workshop upstairs where visitors could paint their own octopus figures in original colors.

We left as the cheerful staff waved and wished us a good hike, then climbed the stone staircase through cherry trees in full bloom.

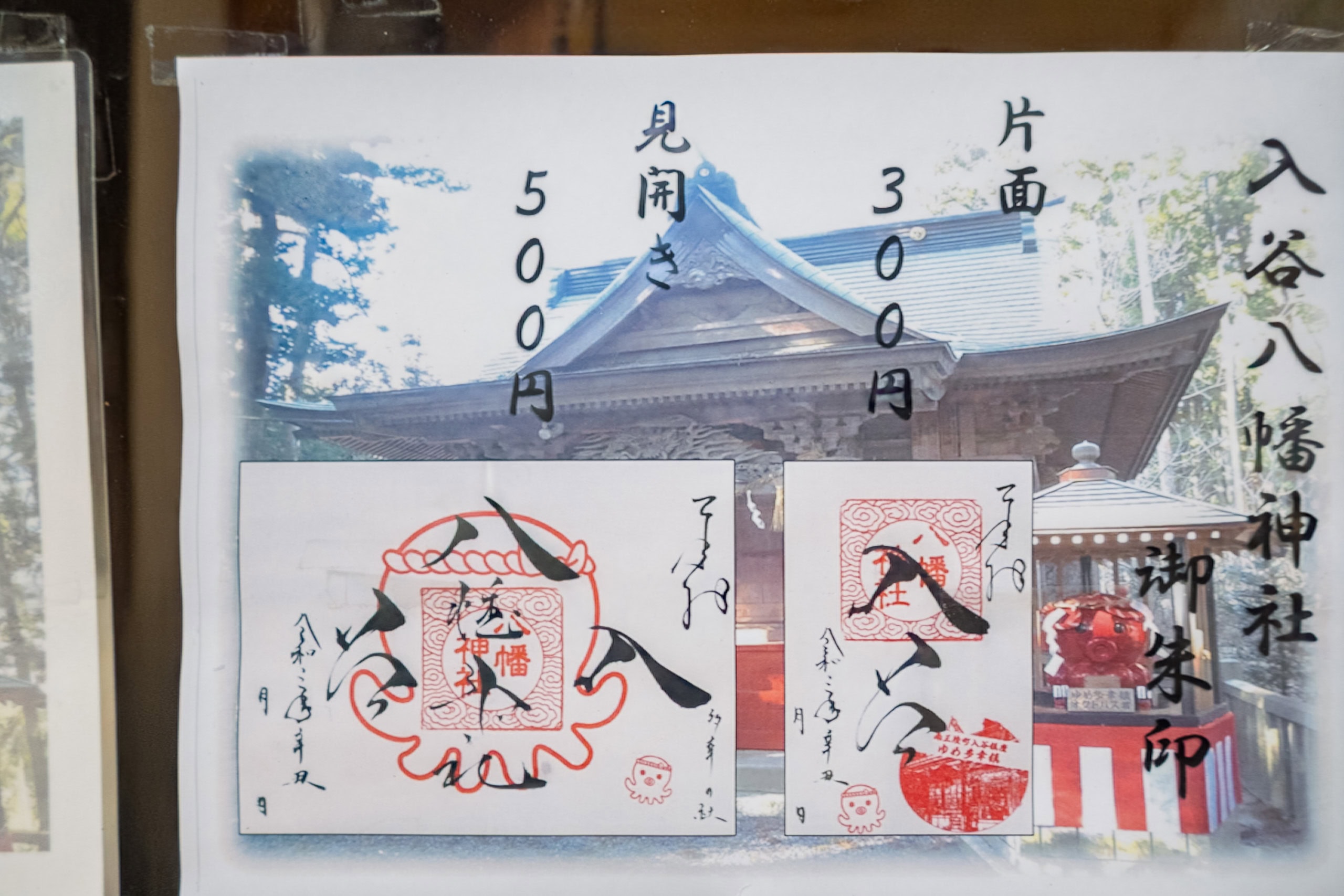

After a few more flights, we reached Iriya Hachiman Jinja Shrine 入谷八幡神社, nestled in a quiet, mystical cedar forest.

Locals often call it by its nickname: the Octopus Shrine.

And of course, right in front of the sacred shrine’s main building sat a giant version of the same cute octopus model…

We loved how consistent the people of Minamisanriku were in promoting their beloved octopus.

This large octopus figure was meant for visitors to touch while praying for exam success.

According to the shrine’s website, octopuses have long been considered symbols of luck in Japan. The word tako (octopus in Japanese) sounds the same as the word meaning “many happinesses.”

Through the Village of Iriya

Through a gate by the shrine, we stepped onto a forest path and walked down the back side of the hill. The idyllic scenery of Iriya continued.

A group of black cows basked in the sun on a small dirt field. At the corner of a cattle barn, a goat family grazed on grass — two tiny white kids bleated softly and watched us with innocent, curious eyes. They were untethered, so small they must have been born only a few days earlier.

I noticed that the style of old traditional houses had changed since we crossed the Ishinomaki–Minamisanriku municipal border yesterday.

In this upland rural area of Minamisanriku, many old houses looked like simple cubes topped with gently sloping tiled roofs, with little decoration. Their walls were dotted with so many windows it seemed as if windows themselves formed the wall.

Each house was surrounded by a beautiful garden of well-tended trees and flowers, usually bordered by neatly kept vegetable plots.

Along the MCT route, we saw several signs and information boards about historic sites. Many noted that this area once produced gold, and that at certain times in history thousands of people had lived here to work the mines.

Although we walked mostly on paved roads, we thoroughly enjoyed strolling through this beautiful village.

For us, whether a hike feels enjoyable doesn’t depend on pavement or dirt but on the surrounding environment and what we see along the way.

Which would you prefer — an unpaved path behind a concrete wall, or a paved road winding through a scenic mountain farming village?

Since yesterday, the scenery around us has been so different from what we saw in the southern part of the MCT. The change has been delightful, and we welcomed it with all our hearts.

Sansankan Schoolhouse Inn

We reached the deepest part of Iriya Village and passed through the gate of an old school. Our accommodation for the night, Sansankan 校舎の宿さんさん館, was once an elementary school.

As Japan’s population shrinks — especially its youth population — rural schools across the country, not just in Tohoku, no longer have enough students and are forced to close.

In most cases, the buildings aren’t immediately torn down, but instead are reused for local purposes. Many former schools have been turned into accommodations for visitors and tourists.

Sansankan has kept much of the original building and interior intact with only minimal renovation. The pre-WWII structure was very old-fashioned, with wooden floors and pillars. Our twin-bedded room had once been a second-grade classroom.

Since it was off-season and during COVID, we were honestly surprised the place hadn’t temporarily closed. If it had, we would have been in serious trouble, facing the familiar problem of finding no place to stay within a day’s walking distance.

Old but well-maintained, Sansankan turned out to be surprisingly comfortable.

We were the only guests that night, so we had the whole building to ourselves. The silence and peace, however, were not just because of that. This was actually the first time since starting the MCT that we stayed somewhere far from the sea or busy parts of the town — here in the middle of a quiet mountain village.

The staff were all local middle-aged to elderly women, and they welcomed us warmly. Even for just the two of us, dinner service was available. Otherwise, we would have had to carry food all the way from the Sun Sun Shopping Village throughout the day.

Dinner was home-style cooking, made with fresh, safe, locally grown seasonal vegetables and fruits, plus seafood from Shizugawa Port.

The only thing missing was a washing machine, but that was a minor issue. We had clean clothes to change into and could do laundry at the next accommodation.

I especially liked the poetic names of the neighborhood and the former elementary school:

山の神平 (Yama no Kami Daira) = Plain of the Mountain God

林際小学校 (Hayashigiwa Shogakko) = At the Forest’s Edge Elementary School

We went to bed early and slept soundly, thanks to the quiet and the absence of lights at night.

It had been a fun, beautiful spring day, filled with a surprise encounter and everything octopus.

Oh, wait.

We still hadn’t figured out the mystery of the Moai…

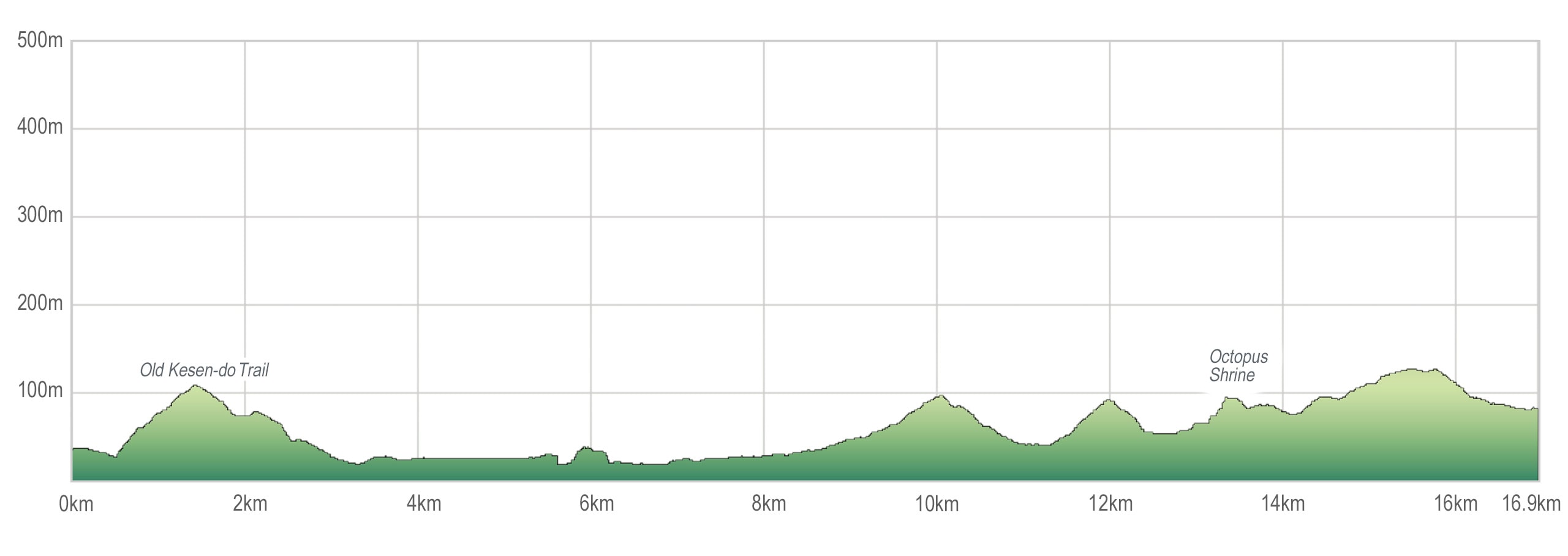

Day 18 – MCT

| Start | Hotel Kanyo |

| Distance | 16.9 km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 327 m/274 m |

| Finish | Sansankan |

| Time | 5 h 39 m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 126 m/16 m |

Route Data

The Michinoku Coastal Trail Thur-hike: late March − mid-May 2021

- The first and most reliable information source about MCT is the official website

- For updates on detours, route changes, and trail closures on the MCT route

- Get the MCT Official Hiking Map Books

- Download the route GPS data provided by MCT Trail Club

- MCT hiking challengers/alumni registration