Back on Track

We were excited to get back on the trail after two full days of rest in Onagawa Town—especially since the day began with a 10-kilometer stretch of nature trails leading up and down the town’s highest mountain, Mt. Ishinageyama 石投山 (455.5 m).

After reaching our goal point for the day, we planned to return to the same room at Hotel El Falo we’d stayed in for the past three nights for one more night.

Finding accommodation beyond Onagawa had been so difficult that it took me several days to come up with a workable plan.

At first, I couldn’t find any place that fit our needs along the next two days’ route. I did see a few minshuku (small, usually family-run inns) on Google Maps, but some were temporalily closed due to the sharp drop in guests caused by COVID, and others were too close to Onagawa to be useful.

By this point, I became confident I could walk more than 30 kilometers in a day as long as the terrain was mostly flat. But once mountains were involved, I knew I shouldn’t overestimate my stamina and leg strength.

So we set our goal for today at Michinoeki Kenjonosato Ogatsu 道の駅硯上の里おがつ, about 18 km via Mt. Ishinageyama. In April 2021, though, there was no place to stay around there.

Would we have to push ourselves to go much farther, or settle for a very short day?

Checking the shop list at Michinoeki Ogatsu, I noticed something: one of the tenants was a branch office of a local taxi company — possible game-changer!

I immediately called to ask if they could pick us up at Michinoeki Ogatsu and take us back to Hotel El Falo.

At first, the booking staff sounded reluctant, saying it “might be difficult” — a very Japanese way of saying no — to have a taxi available for us around the time we requested. In rural areas in Japan with few school-aged children, schools often contract local taxis as substitutes for school buses.

The booking staff explained that late afternoon was their busiest time for this. But then she paused, seemed to think aloud for a moment, and finally, in a much brighter tone, said: “Okay, we can keep a taxi for you.”

“Oh, really? Thank you so much! Then, what time should we be there?”

“Whatever time you want!”

The company was Ogatsu Taxi, and we were deeply grateful that they went out of their way to make it work.

We happily booked a pick-up at 4 p.m. and went to the Hotel El Falo front desk to extend our stay for one more night.

With that, our accommodation problem for the first of the next two days was solved.

Mt. Ishinageyama

Onagawa Town is surrounded by mountains on three sides and bordered by Ishinomaki City, except for its coastline and island territories. Three days earlier we had entered the town via the town’s south mountain, Mt. Dairokutenyama 大六天山, and now we would return to Ishinomaki City by crossing Mt. Ishinageyama.

The last peak in this trio is Mt. Kuromoriyama 黒森山. Trails to these three summits are popular with local hikers, and the town even provides a nice trail map to download on its official website.

First in the morning of our MCT hiking Day 15, we stopped by a convenience store to pick up breakfast and lunch, then headed north out of Onagawa. The forecast promised fair weather all day, but with slightly cooler temperatures. The morning air definitely felt brisker, even without wind.

We passed through a riverside lowland that had been redeveloped into a sports park, and soon entered forests of Japanese cedar. Before long we reached the trailhead for Mt. Ishinageyama.

The climb was steep almost from the start, and I was grateful that we had been able to leave most of our luggage back in the hotel room so we carried much lighter backpacks. The trail was well maintained and clearly marked. Alongside the standard MCT signs, handmade wooden markers pointed the way, showing that this was a beloved day-hiking route for locals.

Halfway up the mountain, thick dark-gray clouds rolled in quickly from the northwest, and a cold wind picked up. Tiny white flecks began to swirl through the air.

“Wait! Is this snow!?”

It only lasted a short while, but yes — it was definitely snowing.

I could hardly believe it, after two weeks of hiking mostly in hot sunshine. We had assumed it would only get warmer as spring went on, but coming from the milder climate of western Japan, we were only now learning what Tohoku weather is really like.

Even after the snow stopped, the sky stayed heavy with clouds, so we quickened our pace.

The last stretch before the summit was brutally steep, but at the top we were rewarded with sweeping views of capes and islands scattered across the blue Pacific under a magically clearing sky.

We took a break in the open area to soak it all in. To the south we could see the mountains and peninsulas we had crossed over the past few days. Far off stood Kinkasan Island, clearly visible.

With the weather still holding, we left the summit and started our descent.

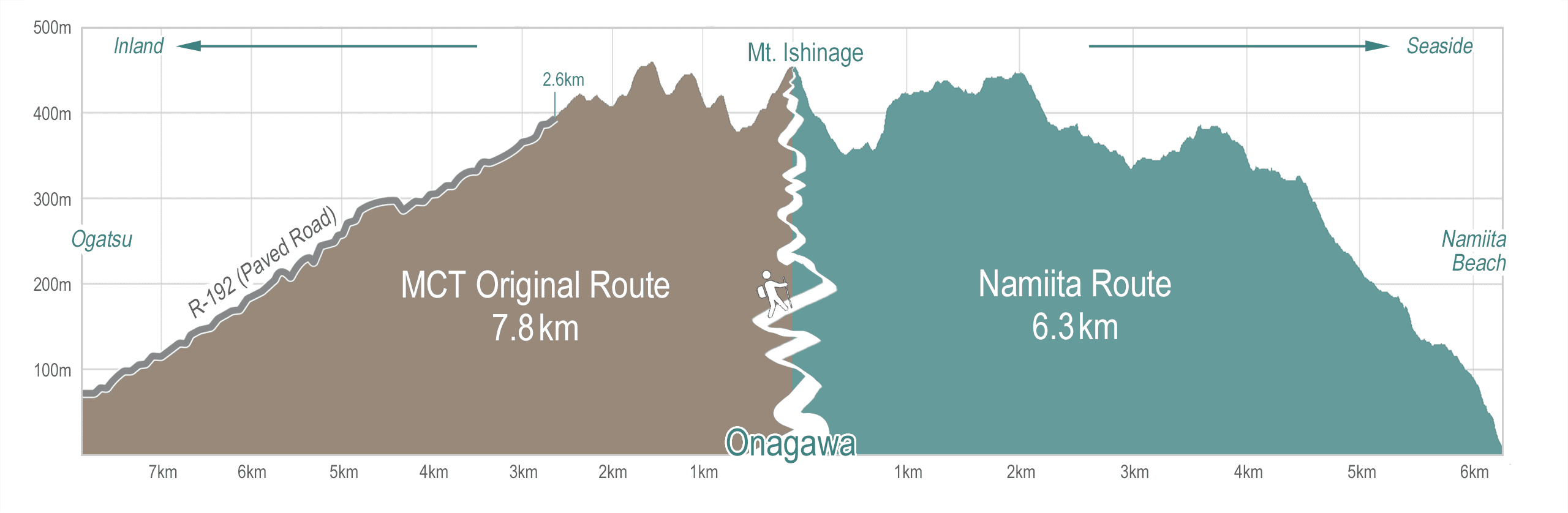

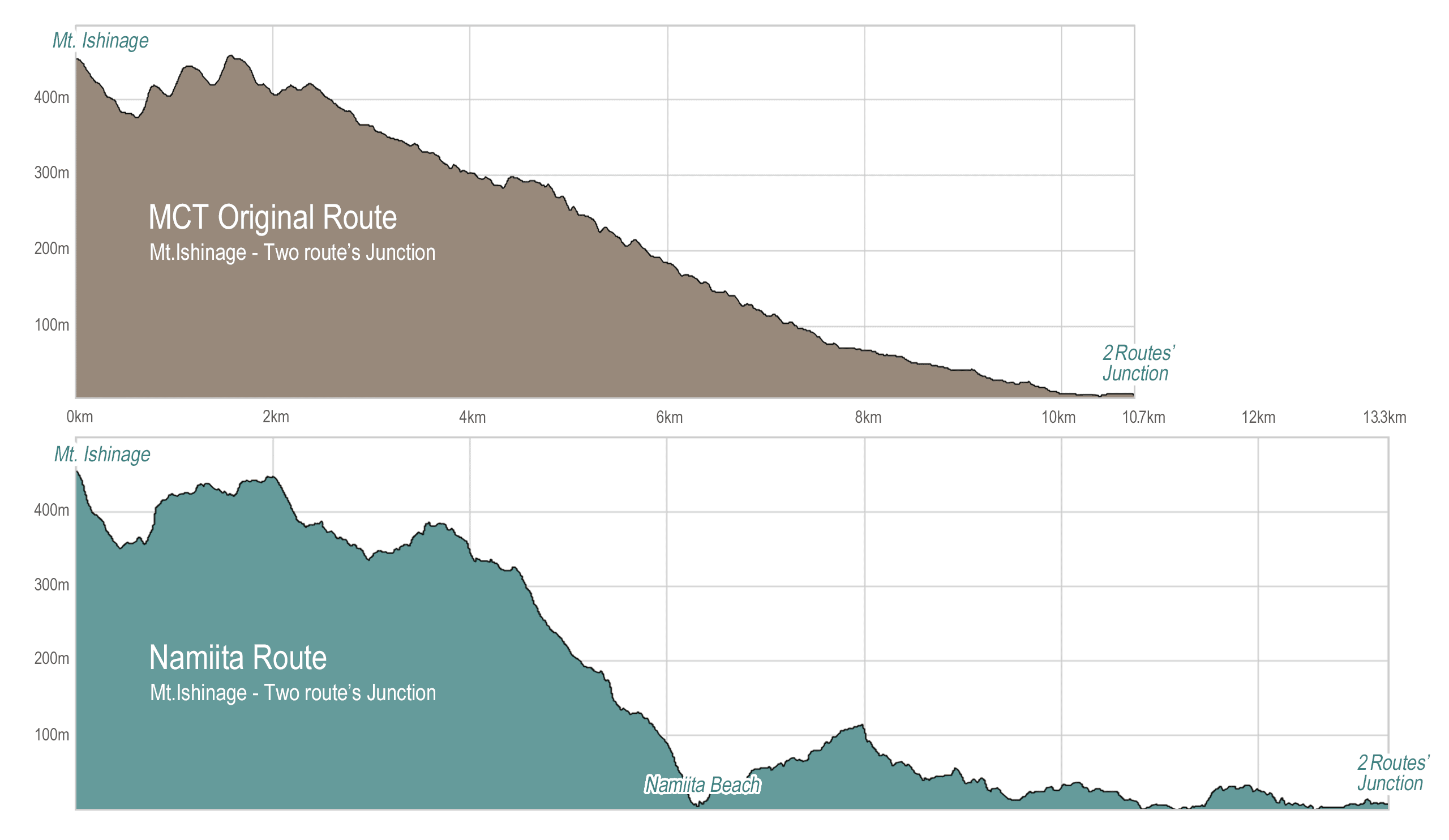

The official MCT route follows the west ridge, but the Michinoku Trail Club had warned hikers that it was blocked by construction at that time. Instead, walkers had to take an alternate route along the east ridge before rejoining a road by the coast.

Unlike the detour to skip the south road of Lake Mangokuura we had been skeptical about on Day 12, this one wasn’t bad news at all.

In fact, looking at the official Map Book vol. 7, the original route switched quickly to a paved forest road, while the alternate kept you on mountain trails for roughly twice as long.

So, we didn’t even consider ignoring the warning this time — we happily walked down the east ridge.

石巻市雄勝エリア迂回ルー-_ページ_2.jpg)

Almost immediately after leaving the summit, clouds and mist crept back in and a cold wind blew, but now the forest sheltered us.

The alternate trail on the east ridge was mostly gentle, with small rises and dips.

Then Erik suddenly stopped, motioned for me to stay quiet, and pointed between the trees.

A white-faced marten with a yellowish body hopped into view. It noticed us, stood briefly on its hind legs as if to study us, and then darted into the brush.

Later Erik spotted another, but this one was warier and vanished before I could get a good look.

As we continued down, darker clouds gathered again and more snowflakes drifted around us.

We pressed our pace, anxious to get out of the mountains before a real snowstorm blew in. Snowstorm in May? You never know. All we knew was we would be in serious trouble if we had one.

Fortunately, by the time we reached the base of the trail, the skies had cleared once again.

Namiita Beach

We came out onto a small, quiet beach called Namiita Beach 浪板海岸.

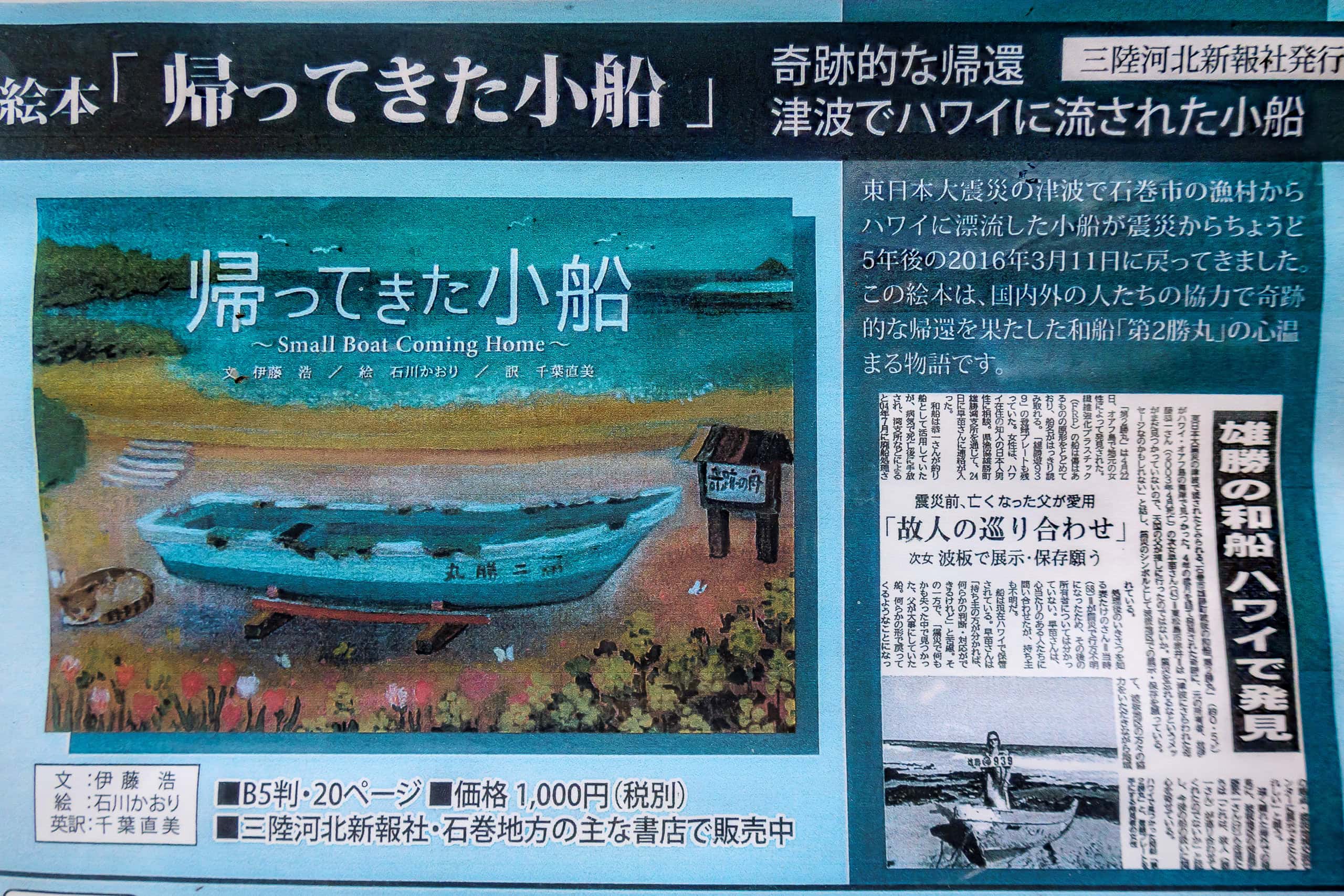

In one corner stood a storage-like building and a simple bathroom hut. Peeking through the windows, we saw a fishing boat stored inside along with newspaper articles posted on the wall.

According to the articles, the boat had belonged to an elderly local fisherman who passed away a few years before the massive earthquake and tsunami ten years ago. When the disaster struck, the boat was swept away from this very beach. Three years later, an American girl in Hawaii discovered it washed ashore on Oahu.

The boat had survived the tsunami and drifted all the way to Hawaii without major damage. Thanks to the kindness of the people of Oahu, it was returned to Japan and brought back to its home beach.

From there, the alternate route followed a road linking small fishing hamlets and bayside ports.

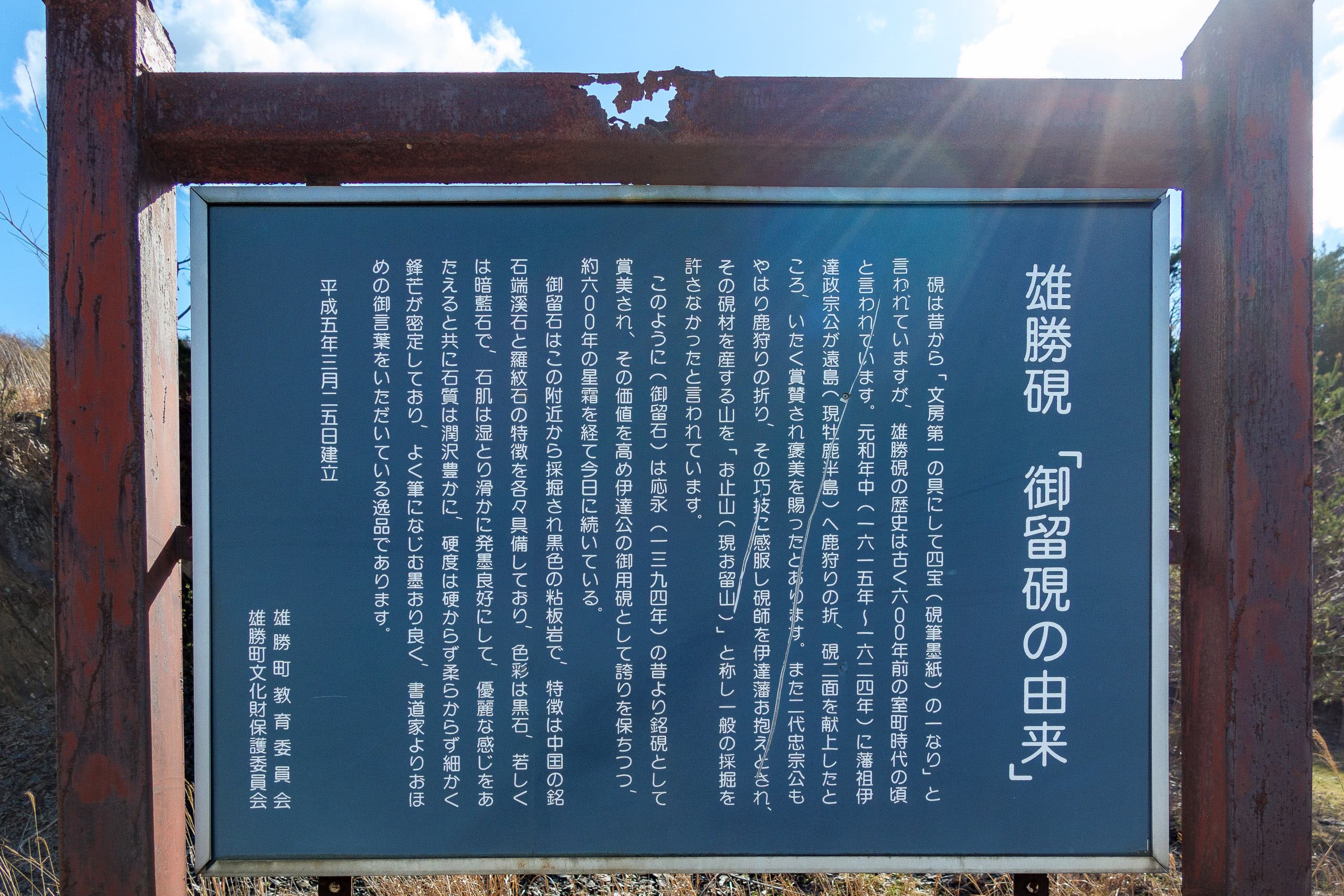

The hamlet near this “survivor boat” beach, called Namiita 波板, had a vending machine in front of what seemed to be the community meeting hall. We gratefully bought hot drinks — the first since leaving Onagawa that morning — and then noticed piles of black stone tiles stacked nearby, along with an information board for visitors.

These black stones were quarried from the surrounding mountains and used for centuries to make high-quality inkstones, tableware, and roof tiles. For over 600 years (!), this area has been renowned for its traditional craftsmanship.

Meet a legend

While a newly built highway ran along the coast, the MCT alternate route followed an older narrow road that hardly seemed used anymore.

Lining it was a row of cherry trees — in full bloom!

During our rest days, the blooming front had caught up with us and probably passed further north. Now every cherry tree in this area was bursting with lovely flowers.

I had heard on a morning news show that once cherry blossoms begin to open in Tohoku, they reach full bloom much more quickly than in the southern parts of Japan. Seeing it here, I believed it.

After enjoying this quiet, flower-lined road, the MCT route merged into the main coastal highway. Just as in many other coastal areas we had walked through, large-scale construction was underway: raising seawalls, widening the road, reinforcing riverbanks.

Because the priority was clearly the port and residential areas, the section we were walking right after rejoining from the old road was still quite narrow, and heavy trucks rumbled past on both sides. At times there wasn’t even room for two to pass comfortably. Sidewalks? Forget it.

We were edging along nervously, annoyed by the constant trucks, when we spotted a hiker coming toward us on the opposite side.

He clearly wasn’t a casual day hiker. His gear and clothing made it obvious: he was a thru-hiker. We called greetings across the traffic.

“Michinoku Trail?” he asked.

“Yes, south to north! Are you coming from the north?”

We were thrilled — it was the first time since we started that we had met another MCT thru-hiker.

(We’d seen a family doing a short day section, but never someone walking the whole trail.)

At first we shouted across the road, often drowned out by the roar of passing trucks. Then he waved us over: “Come to this side, there’s more space.” So we crossed.

Up close, he looked every bit the seasoned hiker. On his pack was a TJAR sticker.

“Wait — you’ve run TJAR?” I asked.

“Yes,” he nodded. “In fact, I help organize the race.”

We couldn’t believe it. His name was Iijima-san, a veteran of the Trans Japan Alps Race (TJAR), one of the toughest ultradistance mountain races in the world.

TJAR is not just a trail running race. Even to apply, candidates must have the skills to survive and navigate through Japan’s most treacherous mountains under any weather conditions, along with proven experience in past races. Through this severe screening process — including both skill and running tests — competitors are selected only from Japan’s very best trail runners. And even then, many fail to finish.

Since 2002, the race has been held every two years. The 13th edition will take place in 2026. Not only during the race itself but even throughout the selection process, Japanese hikers and mountain-lovers follow the progress with excitement.

All competitors, whether they complete the course or not, deserve our praise and admiration.

Iijima-san had completed the race several times in its early years and now served as head of the organizing committee.

No wonder he looked so professional.

He told us he had already walked the northern half of the MCT last December, and now was tackling the southern half, having started just a few days earlier from Kesennuma. His daily pace: 50-60 km.

He laughed that he hadn’t known about the blocked section on Mt. Ishinageyama. He had climbed nearly 8 km up the forest road toward the west ridge before a construction-site traffic controller stopped him and turned him back.

“I wasted 8 kilometers going up and down,” he chuckled—as if it had only been 800 meters.

We traded information — about route changes, blocked paths, accommodation tips. He planned to reach Onagawa that night.

“From here? Now?” we asked, astonished.

It was already after 2 p.m., and he intended to walk everything we had covered since morning.

“I’ll be fine,” he said lightly.

Not wanting to keep him, we exchanged Facebook contacts so we could share route info later by messenger. We explained we had just a few more kilometers before our prearranged taxi back to Onagawa.

I told him that I was amazed at his 60 km days when I could only manage around 30. He smiled and said sincerely, “I think it’s better that way, actually. You should take as much time as you want and enjoy your hike.”

Ogatsu

After waving goodbye to Iijima-san as he sped off in the direction we had come from, we continued walking along the coastline, past the massive construction works, and soon arrived at the Michinoeki Ogatsu.

The final stretch to the Michinoeki was completely shielded by newly built seawalls. Towering up to 10 meters high, the concrete walls blocked our view of the sea entirely. While we fully agreed on the importance of such defenses to protect lives, we couldn’t help feeling a little unhappy at losing the ocean view.

What we didn’t know at the time was that young locals were working to turn the situation into something positive.

They raised donations and invited artists to use the seawalls as canvases. At the end of 2022, the Seawall Museum Ogatsu opened, and new art pieces have been added every year since.

The Michinoeki looked newly built, with a museum of the special black stones and local traditional craftsmanship 雄勝硯伝統産業会館 right next to it.

It was well before 4 p.m., but our taxi was already waiting. I wished I could have checked out the museum, but we didn’t want to keep the driver waiting. So after a quick look inside the Michinoeki and a stop at the bathroom, we hopped in and rode back to the hotel.

Final night in Onagawa

That evening, while eating at our favorite cozy pizza restaurant in the Onagawa shopping mall again, I saw that Iijima-san had posted a selfie from the summit of Mt. Ishinageyama on his facebook and was already on his way down toward Onagawa. Super fast!

The temperature had dropped and the wind was picking up. I sent him a message saying I was glad he had reached Onagawa safely, and warned him it was getting really cold. He replied that he was deciding whether to camp or try to find a lodge.

I strongly encouraged him to stay indoors — it was far too cold to camp.

In fact, on the short walk from the pizza place back to the hotel, it was so cold that I could barely manage without clinging to Erik as a wind shield.

Tomorrow we would finally leave Onagawa, checking out of Hotel El Faro, where we had stayed for four nights. We packed up our backpacks and camping gear boxes to send ahead to our next destination.

Just then, a message came from Iijima-san: he had booked a room at the very same trailer-house hotel where we were staying.

Relieved, we finished our preparations and went to bed early.

Tomorrow would be a long day with our fully loaded backpacks.

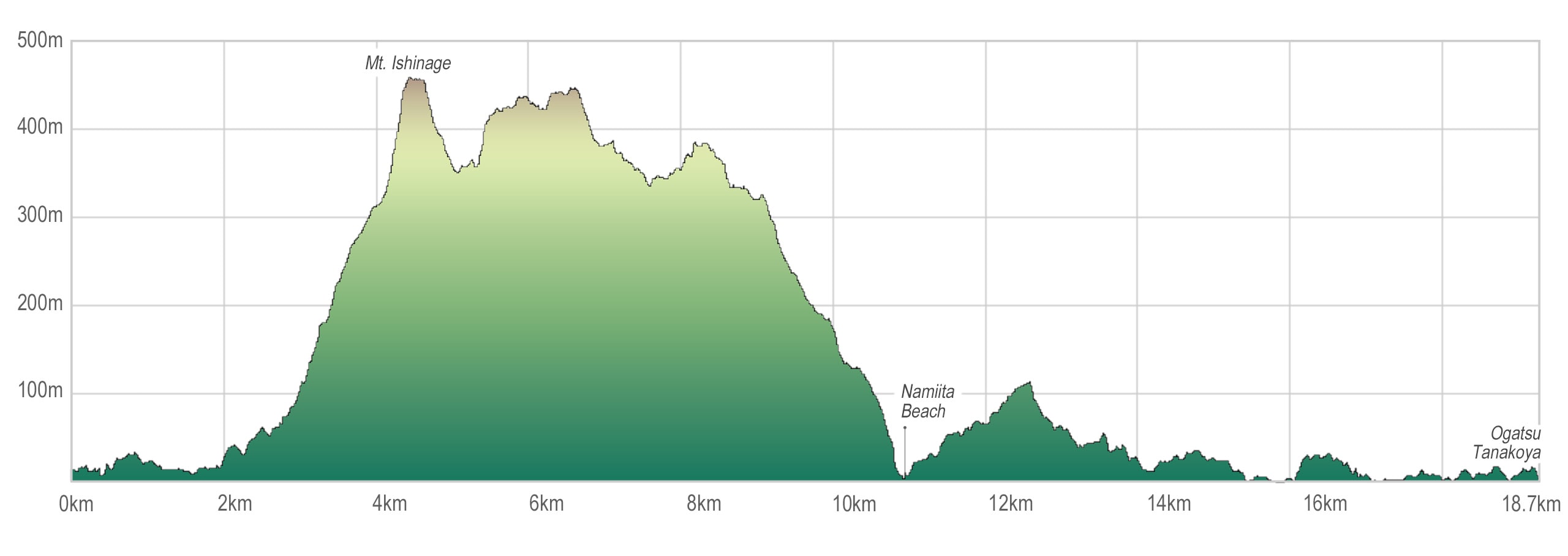

Day 15 – MCT

| Start | Onagawa Station |

| Distance | 18.7km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 673m/720m |

| Finish | Ogatsu Tanakoya |

| Time | 7h 42m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 442m/ 0m |

Route Data

The Michinoku Coastal Trail Thru-hike : Late March – Mid-May 2021

- The first and most reliable information source about MCT is the official website

- For updates on detours, route changes, and trail closures on the MCT route

- Get the MCT Official Hiking Map Books

- Download the route GPS data provided by MCT Trail Club

- MCT hiking challengers/alumni registration

Comments