Lining Up the Supporter Boat

Yesterday, while we were walking around the historic sites in Tagajo 多賀城市, we called Suzuki-san, one of the MCT supporters—local fishermen—who would take us by boat to our goal for the day.

He sounded kind and easygoing. The forecast looked fair for tomorrow, though the swell might build later in the afternoon, so we were good to go. We also outlined our plan: which morning ferry we’d take and when we expected to reach Sabusawajima Port 寒風沢島港 to meet him.

Even though the three islands looked small and the MCT route on each was only a few kilometers, we didn’t want to be overly optimistic. The last thing we wanted was to end up running to make it in time. Meeting at 3 p.m. felt safe. Suzuki-san said he’d come a little early, in case we arrived ahead of schedule.

With that, we were set for our “three islands in one day” adventure.

Shiogama City Ferry to the Urato Islands

Hotel Grand Palace Shiogama ホテル・グランドパレス塩釜 was roughly a ten-minute walk from the ferry port. We checked out at 6:45 a.m. to catch the 7:15 a.m. boat.

We bought tickets for Katsurashima 桂島, the first of the Urato Islands 浦戸諸島 we’d be hiking through, and boarded the ferry. To our surprise, there were already many passengers, mostly older locals. Only a handful looked like visitors, probably heading out for a day of leisure fishing.

Just before departure, a large group of students in matching sportswear rushed aboard, carrying racket bags and calling out to sit together.

With a twenty-minute crossing, we stayed out on deck to enjoy the cool morning air instead of sitting inside. As we pulled away from Shiogama City 塩竈市, snowy mountains stood clear behind the buildings.

Katsurashima 桂島

Only the two of us got off at Katsurashima.

The port was remarkably quiet. Through the day we hardly saw any locals on any of the three islands; most of the people we did see were construction workers building new seawalls and roads.

Miyagi Prefecture had declared a state of emergency due to COVID after a sudden rise in cases. We weren’t sure if the silence was related, but as visitors from outside Tohoku, the last thing we wanted was to make people uneasy. We kept to ourselves and enjoyed the walk, without seeking out encounters.

All three ferry ports had tidy waiting shelters, modern bathrooms, and vending machines. As expected, there were no grocery stores or shops along the MCT route.

We passed a few houses, then the route led through a small shrine into the woods behind.

One thing stood out: every shrine we saw on these islands had large bells—the kind we normally see at Buddhist temples. We’ve visited plenty of temples and shrines across Japan, but it was our first time seeing such bells at Shinto shrines.

Maybe it’s not so strange. In earlier centuries, Buddhism and Shinto weren’t strictly separate; they often stood side by side until the Meiji era, when the government split them.

On tiny, sparsely populated islands like these, maintaining both separately probably wasn’t practical anyway.

The path wound through tunnels of hardy oaks and other common seaside trees, with openings to viewpoints over the clear blue sky and sea.

Eventually we reached the far side of the island and looked down on a quiet sandy beach. I was a little excited — it was the first sandy beach we’d seen since starting the MCT.

I always pictured MCT hikers walking along endless beaches. I’m sure those promotional photos weren’t taken here, but I still wanted to do my first sandy beach walk.

The official route stayed behind a seawall at the edge of young pines, so hikers didn’t actually need to step on the sand. But who could pass it up? We dropped down and walked along the dry edge, as close to the waves as we could.

After that short, satisfying beach walk, we rejoined the trail. It soon met a narrow road running through the middle of the island. The road climbed, passing a neighborhood of newly built houses. We could sense people lived there, but we didn’t see anyone — probably working at the port or out fishing.

We took a short break at a hilltop bed of yellow narcissus. In the middle stood a white bench with a “Welcome to Katsurashima” sign. Clearly, locals had created this small viewpoint for visitors; I imagine they would have loved to see travelers enjoying it again this year, if not for COVID.

On the eastern side we passed through more woods, then reached the site of a wealthy fisherman’s former house. In the nearby cliffs, square, man-made holes caught our eye — too regular to be natural. According to tourist information, they were used to store fishing tools.

Much earlier than expected, we reached Ishihama Port 石浜港 on Katsurashima’s east side. The island is long and thin, stretching west to east, and the port where we’d landed that morning sits on the west.

From Ishihama Port we would cross to Nonoshima 野々島 by free, city-run motorboat.

Hikers can still take the Shiogama City ferry to Nonoshima from Katsurashima, but the small city interisland motorboat is simpler: no timetable — just call the number posted on the shelter wall during operating hours. It’s free, too.

After a couple of rings, the operator answered. The boat was on the Nonoshima side but would come right away. Sure enough, we saw it leave the opposite port and head straight toward us. How convenient.

We waved from the dock, and a few minutes later the boat pulled in. The operator took us aboard and immediately headed back toward Nonoshima.

Nonoshima 野々島

The crossing was over in no time.

At the port, a vending machine by what looked like the waiting lounge carried Erik’s favorite milk tea — even hot.

By then the day had turned warm and bright. We passed a few houses and climbed to the village shrine hill. From there, an old path wound beneath tunnels of camellia.

Nonoshima is the smallest of the three islands we hiked that day, and the MCT route here was distinctly shorter—almost a straight line across the island.

We already knew the motorboat to the last island would be just as quick and convenient as the previous one. In the end, the buffer we’d built for waiting wasn’t needed.

When we saw a sign for a short detour — the “Path of Camellia” — I convinced a hesitant Erik to try it. Otherwise we’d have been far too early to meet Suzuki-san, and the name was too good to skip.

Beyond the Path of Camellia, the northern beach looked like a place for kids to kayak or swim, but it was empty during spring break. The map showed an herb and flower garden behind the beach, but all we saw were dried lavender stalks — too early in the season.

Back on the MCT route, which climbed over a small hill near the island’s center, we eventually found a portable restroom — oh, nice!

While I was inside, I heard Erik talking with someone.

Outside, a local elder was trying to chat with him in broken English and gestures. I recognized him: we had passed him earlier, tending a small flowerbed along the route, and as always we’d greeted him with a “Konnichiwa.”

It wasn’t the first time elderly fishermen in remote Tohoku villages had struck up English with Erik.

Some speak surprisingly well — many worked abroad in their youth on long-distance fishing boats or at overseas fish farms.

With my help translating, the older man shared his family story.

His father was sent as a Japanese soldier to an island in Indonesia during World War II. It was one of the deadliest battlefields, and none of the other men from his fishing village returned. When the war ended, starving and near death, he had almost given up hope of seeing home again. Then the Dutch Army arrived to disarm the Japanese forces — and ended up saving his life.

Back on Nonoshima, villagers had already received word that all their men had been killed, so no one expected him back. Against all odds, he came home alive.

The elder man told us he had been only a toddler then, but he still remembered his father saying that Dutch soldiers treated him kindly and arranged his safe return to Japan.

Because of that, he grew up with a deep gratitude toward both the Dutch and the Indonesian people. He had always hoped to meet someone from the Netherlands to express that feeling, but until now he had never had the chance. Meeting Erik filled him with excitement.

“My heart is so full… I can’t describe how glad I am to see you here,” he said, smiling.

He showed us the beach below the flowerbed where he used to play and swim as a child, while his mother grew vegetables on the hill. His mother’s former vegetable field had long been abandoned and was growing over.

“I retired last year and have plenty of time now,” he said, shaking Erik’s hand.

“I want to clear the hill and add benches, so future visitors can enjoy it.” His eyes shone with determination.

Carrying his warm words and story with us, we walked on and reached the island’s east-side port. As before, I called the direct number for the motorboat; it was waiting across the water and came right over.

Sabusawajima 寒風沢島

Sabusawajima 寒風沢島 looked so close — probably no more than a hundred meters away — that good swimmers could have crossed it. I imagine kids and young fishermen once did.

After the shortest ride yet, we stepped onto our final island. The port where we landed was also where we’d eventually depart. Unlike the other islands, the MCT route here forms a loop around the island.

The port was quiet except for a few construction workers building new roads and seawalls. After checking another vending machine and bathroom, we set off counterclockwise around the loop.

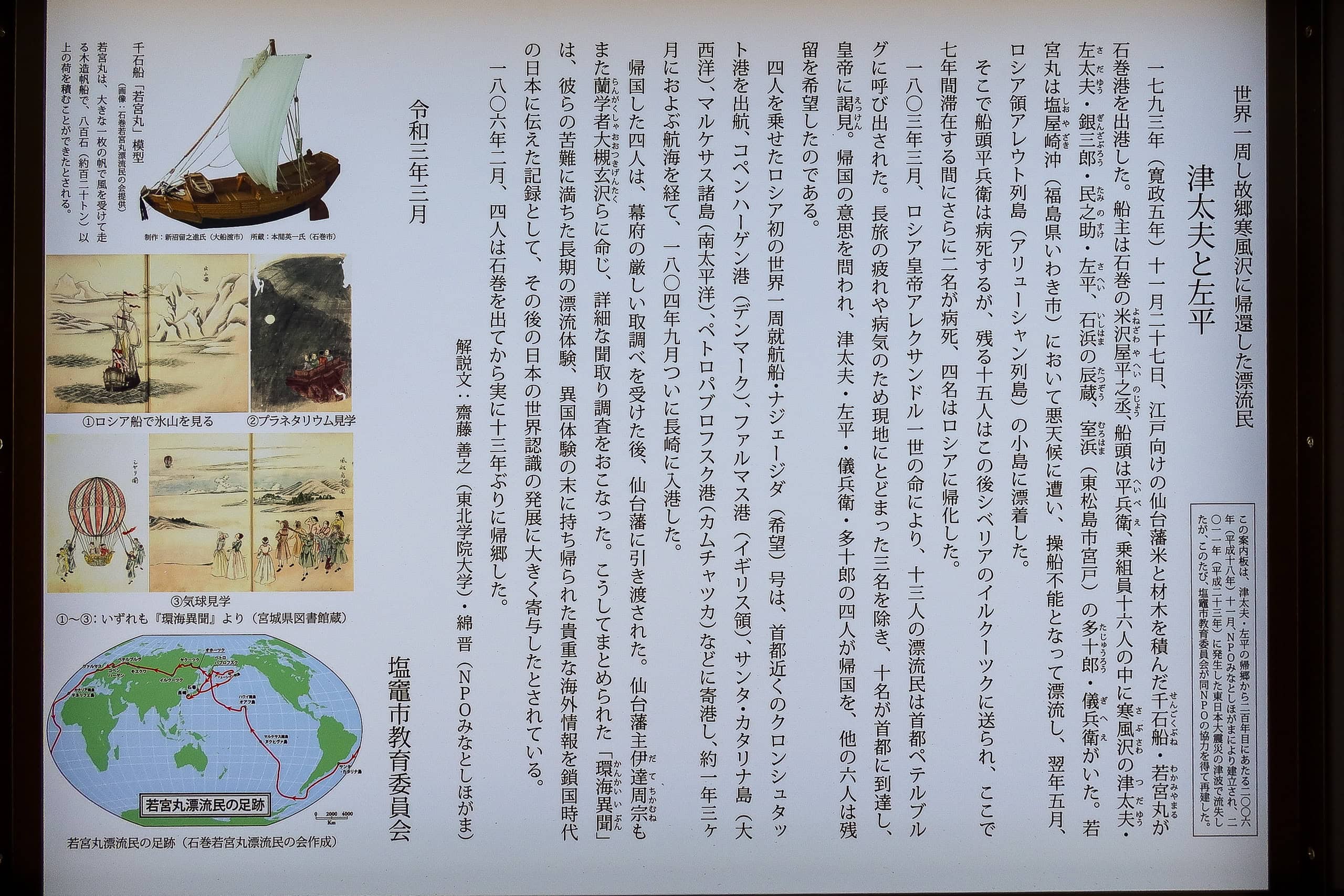

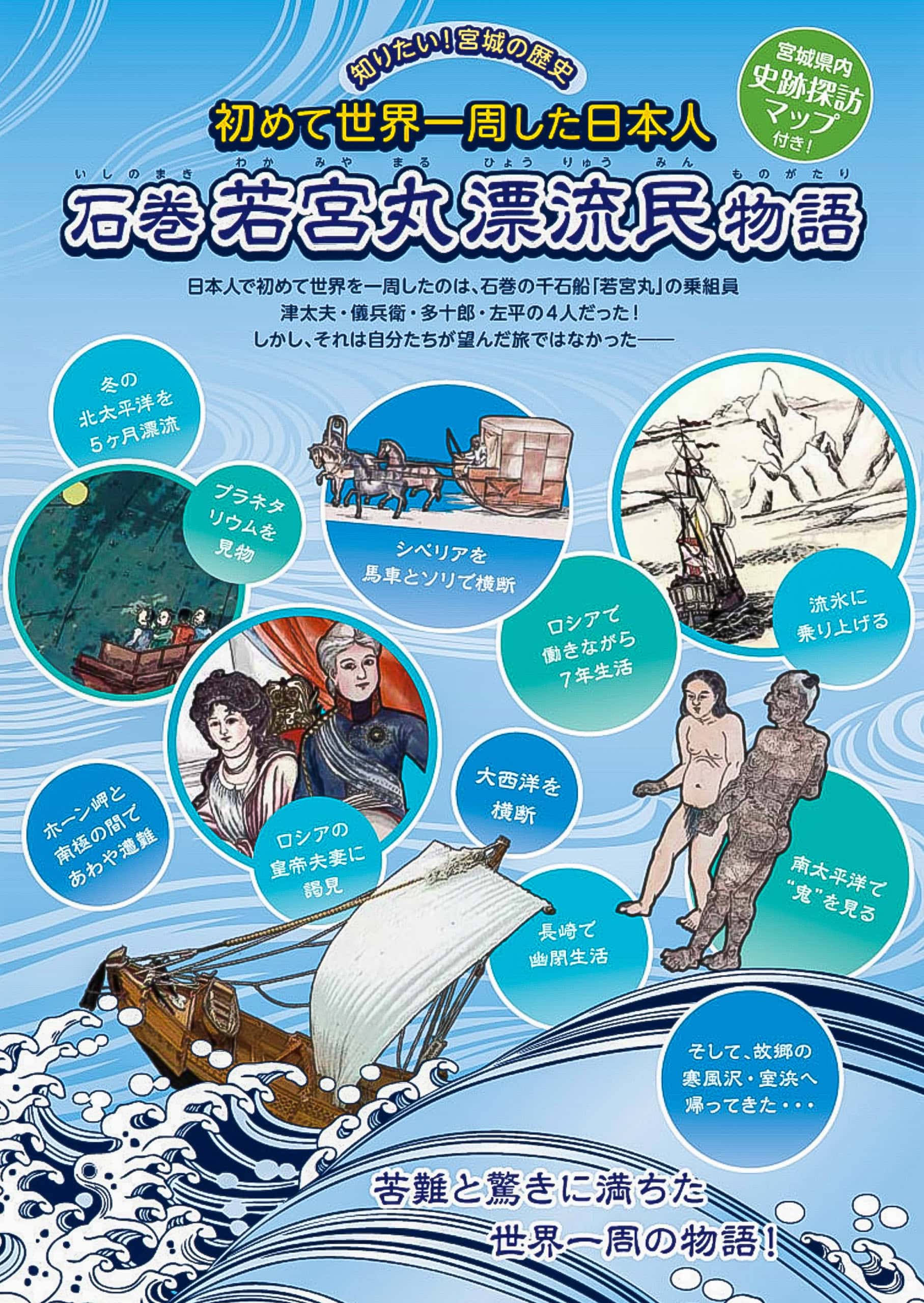

Soon we came across an information board with a striking story.

The villagers here were considered the first Japanese to have traveled around the world.

Were they explorers? Not exactly — they were crew members of the Wakamiya-maru 若宮丸, a cargo ship transporting rice and logs to Edo (Tokyo’s old name) in 1793. A storm blew the ship adrift for five months until it reached one of Russia’s far northern islands.

What followed was years of hardship. Some crew died, some remained in Russia, and only four eventually returned to Japan in 1804 — ten years later. The Russian vessel that brought them home became the first Russian ship to sail around the world.

Even after the survivors reached Japanese waters, they were interrogated harshly; Japan was still closed to the outside world, and going abroad — no matter the reason — was considered a crime. They finally returned home in 1806, thirteen years after leaving.

Later at our lodge, I found an eight-page brochure with more detail. Two of the men died just a few years after coming home, one even attempting suicide. Their story was sobering.

The MCT route first climbed to a hilltop viewpoint, where we found a stone Jizo 地蔵 statue tied with ropes. The tourist map listed several theories. One suggested that women at an old brothel once prayed there for rain to keep their guests from leaving.

The loop around Sabusawajima went by quickly, just as we’d guessed.

After a short stretch through woodland, we stepped into a vast, empty clearing.

“Is this an MCT thing — making us walk in the middle of nowhere?” Erik joked, half-sarcastic, remembering all the “endless flat fields” we’d crossed in previous days.

The map explained that this clearing had once been rice paddies, sustained only by rainwater. With the island’s aging, shrinking population, most had long been abandoned. Only one small patch still showed signs of cultivation.

Across the three islands, we noticed oyster shells being put to good use — filling holes and smoothing rough patches of road.

Supporter Boat to Miyato: A Short Cruise

Rewinding a few hours: while walking on Katsurashima, Suzuki-san texted me. If we finished early, he said, he could take us on a short cruise around the islands instead of heading straight to Miyato Island 宮戸島. At the time we weren’t sure, but he clearly knew better than we did — we ended up finishing far earlier than expected. At 12:45 p.m., we were back at the port, and the island hiking was complete.

I called him. He was already waiting across the water on the Nonoshima side. Minutes later, his fishing boat cut through the waves toward us.

His fishing boat was smaller than the inter-island motorboats.

We sat on a wooden bench he’d installed and put on life jackets. Erik, much bigger than the average Japanese man, managed — just barely — to fit into the largest size that Suzuki-san had brought specifically for him.

Then the boat pulled away, accelerating south toward the open sea instead of heading straight to Miyato.

Unlike the big, steady ferries, this boat felt like it was skimming the water. With no shelter or railing, we felt the wind on our faces and the speed in our stomachs — fast and thrilling.

Suzuki-san handled the boat smoothly, steering around the larger waves so we never slammed hard. Sometimes he idled the engine, pointing out rocks and islets, explaining the geology of the Urato Islands, and showing us oyster farms scattered everywhere. It was a special tour.

We cruised up the east side of Sabusawajima, slipped through the narrowest strait between it and Miyato — only about 80 meters wide — and arrived at a dock on Miyato Island at 1:30 p.m.

Our sea journey was over: Miyato Island is connected to the mainland by bridge.

Suzuki-san told us we were his first hikers of the season — no surprise, since April 1 was the first day of the 2021 supporter-boat service.

He pointed to a hill behind the dock: “You should climb up there for a great view of all the Urato Islands.”

He also asked where we’d be staying. When we told him, he smiled — he knew the owner. “That place is excellent. The food is exceptional. You chose well.”

Otakamori & Miyagi Olle Trail

Since we had arrived hours earlier than planned, we had time to explore. We climbed Otakamori 大高森, which means “big, high forest.” The trail was easy — 15 to 20 minutes — and the 360-degree view from the observation deck was breathtaking.

To the west we could see small islands dotting the sea.

To the northeast lay our goal for tomorrow: a long beach stretching far into the distance, with a very flat inland town beside it.

We already knew what kind of fate awaited us…

Miyagi Prefecture also has a series of shorter trails called Miyagi Olle 宮城オルレ. Unlike the MCT, they aren’t connected but are scattered around the prefecture. One of them is here in the Oku-Matsushima 奥松島 area, and Otakamori is part of the 10-kilometer route.

The Olle trail continues along the Otakamori ridge, away from where we came in. We followed it for about 2 km until it met a road that led us back to the fishing village and our accommodation.

Fish Feast at Minshuku Sakuraso

Our minshuku — Sakuraso — sat in a quiet village near a Jomon-period 縄文時代 (14,000 to 2,300 years ago) history park. The bath overlooked the seaside park, and I soaked in the hot water, watching the waves through the large windows.

Before dinner we wandered to the village’s only shop for snacks and drinks. It was off-season, and COVID made things even quieter. The store had little to offer, and, honestly, we felt a little unwelcome as outsiders. Understandable — most villagers were elderly and needed to be cautious.

Back at the minshuku at dinnertime, we understood why the online reviews kept mentioning the portions. When we sat down, the table was already crowded with seafood dishes. Then came fresh sashimi, steaming rice, and miso soup.

Just as I was struggling to finish, two more WHOLE fish — one fried and one grilled — were set in front of each of us. The reviews weren’t exaggerating.

I love fish, and everything tasted great, but I had to wonder: was this really a normal portion for an average adult?

That night, I surrendered. I couldn’t win against the fish, fish, fish festival.

Honestly, who could? If you manage it, let us know.

Day 7 – MCT

| Start | Marin Gate Shiogama |

| Distance | 30.5 km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 187 m / 192 m |

| Finish | Minshuku Sakurasou |

| Time | 9 h 27 m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 102 m / 0 m |

Route Data

The Michinoku Coastal Trail Thru-hike : Late March – Mid-May 2021

- The first and most reliable information source about MCT is the official website

- For updates on detours, route changes, and trail closures on the MCT route

- Get the MCT Official Hiking Map Books

- Download the route GPS data provided by MCT Trail Club

- MCT hiking challengers/alumni registration

Comments