The Oldest Recorded Pilgrim Trail in Shikoku

(Continued from Day 20.1)

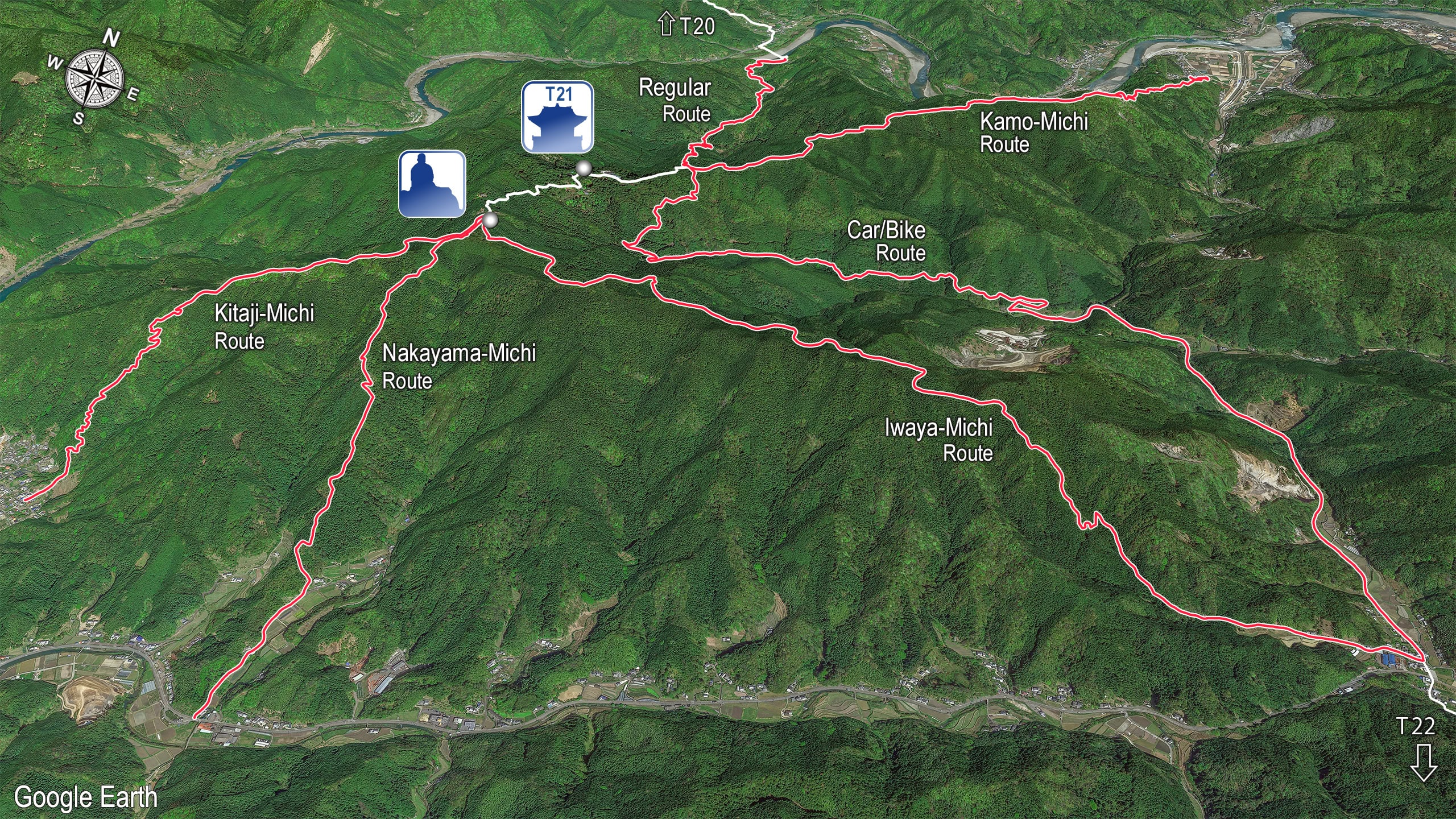

It’s a pity that the Kamo-michi かも道 stays so underrated among walking pilgrims, despite its history, varied scenery, and the many story-rich sites tucked along its 4.5 km length.

Kamo-michi is often called “the oldest pilgrimage trail in Shikoku.” Several stone distance posts still stand along the way; one bears an inscription dated A.D. 1365.

The stone-paved approach to T20 also preserves ancient distance pillars like those on Kamo-michi, but its oldest is a year younger than the 1365 marker. So far, no older waymarker has been found anywhere on Shikoku.

I’m sure other Shikoku Pilgrimage paths are just as old — perhaps older — but they lack dated stones or grave markers to prove that people were walking there 650+ years ago.

If Kamo-michi has a reputation problem, it’s probably this: the extra 3 km from Suii Bridge to its trailhead. Many pilgrims are already racing daylight to cross two 500-meter-plus mountains (and a smaller one) to reach T22 after visiting T20 and T21; a detour can feel impossible.

Why is Kamo-michi’s trailhead so far from Suii Bridge, and why does it approach T21 太龍寺 from such a different angle?

Long ago, pilgrims didn’t drop to the Suii valley after T20. Until a few decades back there was no bridge at all — elders in their mid-70s still remember crossing the Nakagawa to school by small boat.

Centuries earlier, after T20, pilgrims would keep traversing east on a high path along the mountains, only dropping to the valley near today’s Kamo-michi trailhead to cross the river.

An early Shikoku Pilgrimage guidebook published 335 years ago (in 1687) describes the route from T20 to T21 at that time: the line that drops straight to where Suii Bridge now stands and climbs today’s Tairyuji-michi was the shortcut.

Although nearly every temple on Shikoku has a legend linking it to Kōbō Daishi, he named only two places in his own writings: the sacred cave near T24 and the mountain of Tairyu. When he climbed to T21, he most likely used Kamo-michi.

(Side note: he wrote “Tairyu Mountain in Tokushima” without naming a temple, which leaves room for B20 Otakiji 大瀧寺 to claim they are the “true” site…)

For roughly three centuries after that oldest distance post was set, pilgrims seem to have looked for faster ways to reach T21, and their feet carved a new line.

So the location of Kamo-michi’s trailhead makes sense. And just as pilgrims once avoided dropping all the way down to the other side of the ridge, today’s time-pressed walkers often avoid it too.

The result is that Kamo-michi remains genuinely off the beaten path for Shikoku pilgrims — even as it gains a new following among local day hikers and trail runners who use it for training.

I could write dozens of pages only about Kamo-michi. I got a lot of hands-on knowledge and old stories about it from my older friends whose families have lived in the area for generations (the oldest one can trace back their family lines through 14 generations.)

But for now, let’s move on to the latter half of our Day 20.

The Kamo-michi Trail

The Kamo-michi trail begins right beside the gate of Isshukuji Temple 一宿寺 — so don’t go inside. Near the entrance, you’ll see several old, broken stone distance markers that were collected from the mountain and preserved there.

The entire 4.5 km length of Kamo-michi — or roughly 10 km if you combine it with the Iwaya-michi route — remains unpaved and natural, carefully conserved to preserve its historical form without damaging the landscape.

After a short but steep beginning, the trail continues climbing gently through bamboo forests.

Soon the path turns steeper and rougher, zigzagging upward through a mixed mountain forest. About one kilometer from the trailhead, the entire slope suddenly changes color — the ground and cliffs now bright with white stones and boulders.

The mountains around T21 are formed of massive limestone and marble. Old quarries can still be found along the pilgrim paths, and this white-stone section of Kamo-michi is one such area.

From a small viewpoint here, you can look back toward T20 and the valley villages far below.

Folklores on the Kamo-michi Trail

Along the Kamo-michi trail, a few places are tied to curious legends and folktales that blend humor, reverence, and a touch of imagination. For example:

An old stone monument marks the spot where Kōbō Daishi is said to have flown to T20. Clearly, he could fly — and was apparently even more impatient than the 17th-century pilgrims who sought shortcuts.

When a huge marble boulder tumbled down a mountainside, Kōbō Daishi stopped it with a single punch from his left hand. The imprint of his fist still remains on the rock today.

A massive, mountain-shaped rock said to be crawling toward T21 from Isshukuji Temple. The legend warns that when it finally reaches the temple, the world will sink into mud. Thankfully, the rock moves “only a rice grain’s length” each year. That means it’s taken 300,000 years to reach its current spot — and will need at least three times more to finish the journey.

After a short, steep, and slippery climb through white limestone, the path leveled off and continued gently for the remaining 3.5 km, until meeting the Tairyuji-michi 太龍寺道 route — the main trail used by most pilgrims.

Another route joins Kamo-michi and Tairyuji-michi at this connection point: a concrete forest road — the only way cars and motorbikes can reach the mountain, unless pilgrims take the ropeway. About one kilometer below this junction is a parking area, so even car pilgrims must walk the final steep stretch. The parking fee is 500 yen per car, payable at the stamp office.

Motorcyclist pilgrims can pass the car park and ride farther up to the temple’s main gate, where a small parking area sits behind it.

Occasionally, you may see a small truck or car driving all the way up to the temple buildings — but don’t frown. They’re monks, staff, or contractors with special permission.

Most cyclists probably choose the easier way: leaving their bikes at the ropeway base station (Michi-no-Eki Washinosato 道の駅 鷲の里 and taking the ropeway up and back. The forest road is narrow, steep, and twisting, with long stretches of cliff-edge and no guardrails — hardly a relaxing ride downhill.

At the stamp office, we met a familiar face — the assistant priest-monk who has always been kind to us and from whom I’ve learned so many stories and bits of temple history.

I bought some stickers of the temple’s main deity, Kokuzo Bosatsu 虚空蔵菩薩, to decorate my iPhone case, along with a few protective charms.

Knowing we would soon leave Japan for a time after this pilgrimage, he quietly chanted mantras over the charms, infusing them with prayers for protection during our travels.

Though T21 is a large temple, it’s maintained only by the monk’s family and a few long-time staff members. We know all of them and have countless warm memories here.

I’ll miss this beautiful temple deeply.

Can’t-Miss Features at T21

I could write an entire essay about T21, but here are a few highlights that many pilgrims — especially international visitors — often miss.

Look up inside the large hall that also houses the stamp office: above the long interior corridor, behind the sliding glass windows, a dragon coils across the ceiling. The center windows are usually left slightly open near the offertory box so visitors can lean in and gaze upward.

You’ll also find the same dragon motif on T21’s original tenugui (light cotton towel) sold at the stamp office — one of my favorite hiking essentials and a perfect, lightweight souvenir.

Why a dragon? The name Tairyuji literally means “Temple of the Great Dragon.”

As noted earlier, the mountains around T21 are massive blocks of limestone and marble. High-grade marble from these hills was used in the construction of Japan’s National Diet Building. Between the stamp office and the main precinct, and again between the Daishi-dō and the pagoda, you’ll climb marble steps — a rare detail most people miss.

T21’s nickname is “the Western Koya.”

“Koya” refers to Koyasan, the spiritual center of Shingon Buddhism and a UNESCO World Heritage site in Wakayama. There, Kobo-Daishi entered eternal meditation in A.D. 835 in the inner sanctum of Okunoin; tradition holds that he remains in meditation even now, which is why monks still carry meals to him twice daily.

Okunoin itself is among Koyasan’s most visited sites, famous for its vast ancient cedar forest cemetery.

A small river divides the public cemetery from the holy precinct; visitors cross a stone bridge, remove hats, and refrain from photography beyond that point. Behind the main hall lies the true sanctuary: a small, hidden shrine protecting the room of Kobo-Daishi.

At T21, unlike most of the other 87 temples, the main hall and Daishi-do stand apart. A little stone bridge on the path to the Daishi-do evokes okunoin’s approach. The Daishi-do itself is a beautiful, solemn structure with finely carved pillars and panels.

Just as pilgrims at okunoin walk quietly to the inner sanctum, visitors at T21 are encouraged to step onto the outer corridor of the Daishi-do and continue around to the rear. There you’ll find a small, exquisite shrine set against the cliff. Inside, a hidden statue of Kobo-Daishi is enshrined; if you wish to offer prayers, this is the most fitting place.

Inspired by these parallels in landscape and layout, people began calling T21 “the Western Koya.”

And here’s a rare grace note: while no one may view Kobo-Daishi’s chamber at Koyasan, T21 opens the little rear shrine once a year, allowing visitors to see the statue within. The date changes annually because T21 follows the lunar calendar, timing the opening to the day Kobo-Daishi is believed to have entered his eternal meditation nearly 1,190 years ago.

The reason the young Kobo-Daishi (then known by his monk name, Kukai) came to this temple was to undertake a special esoteric Buddhist practice called Gumonji-ho 求聞持法, a disciplined path toward enlightenment.

According to temple legend, he performed this training on a cliff south of the temple, where a large bronze statue of him now sits. It’s said he didn’t attain enlightenment here, but later succeeded when he repeated the practice inside the sacred cave near T24.

For more than 1,200 years, T21 has remained one of the few temples in Japan that still preserves the secret teachings of Gumonji-ho. Even today, a small number of monks and nuns come each year to receive these oral instructions and complete the practice.

For ordinary people like us, the simplest outline of Gumonji-ho is this: the practitioner chants the mantra of Kokuzo Bosatsu 虚空蔵菩薩 — T21’s main deity — one million times. But of course, the actual practice is far more complex.

As the monks explained to me, practitioners undergo a demanding 50-day retreat in a small hut near the main hall, following strict rituals both physical and mental. The hut’s walls and the surrounding slopes shield them from the outside world, and all contact is forbidden until the training ends. Visitors will never see them; even passing nearby is discouraged.

Spotting a sand-yellow monk’s robe hanging to dry outside the hut, we realized someone was inside — quietly repeating the same secret discipline that young Kukai once practiced here.

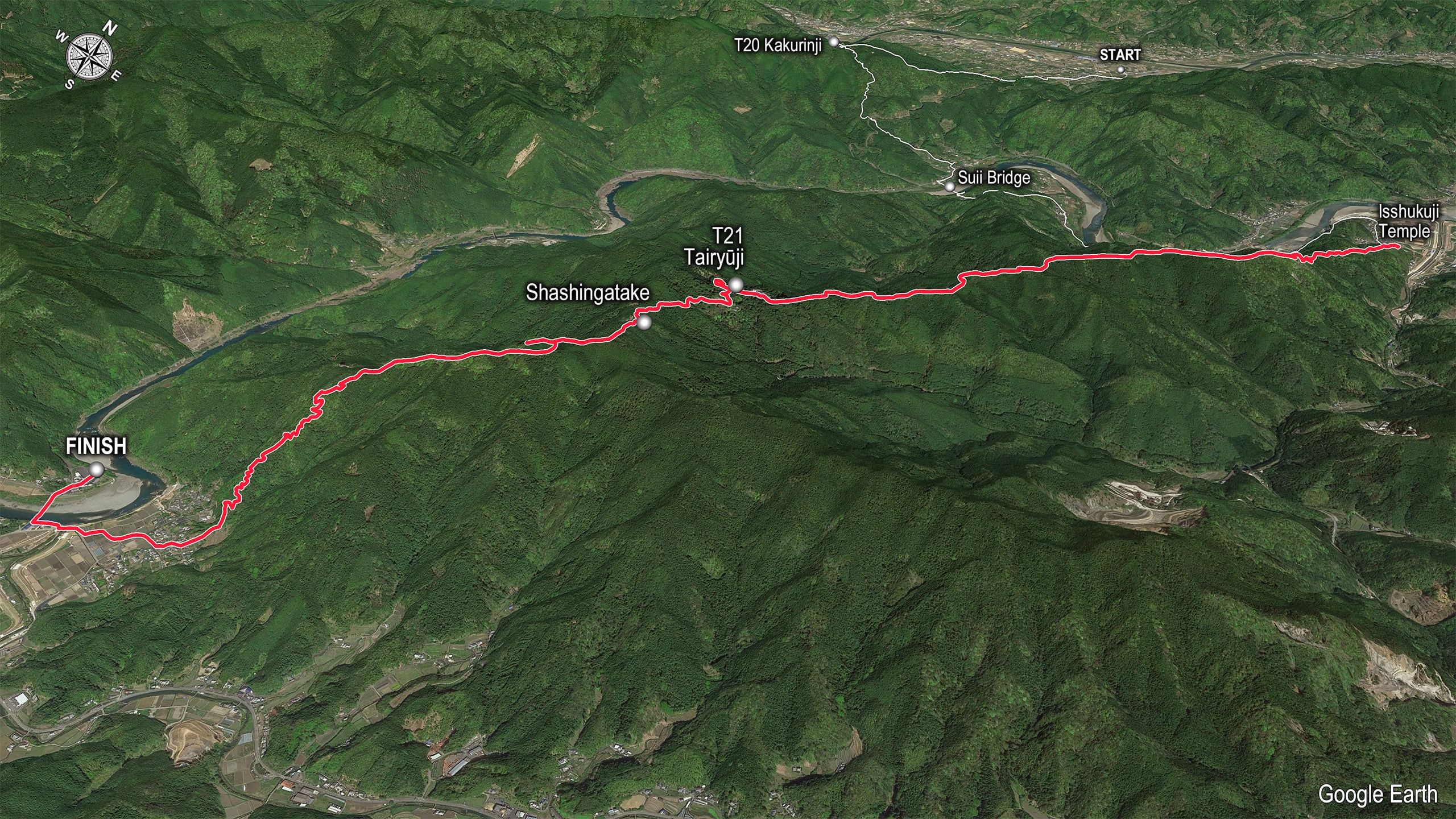

To Shashingatake — The Sacred Cliff of T21’s okunoin

I turned once more to look back — a quiet goodbye in my heart to this beloved temple — before descending the long stone stairs from the main hall toward the ropeway station, where we stopped for one last vending machine and restroom break.

It was already 3:30 p.m. when we finally left the station to head toward Shashingatake Cliff. I was grateful that it was the height of the long-daylight season and that the weather was brilliantly clear. Had it been winter, we would have needed to be off the mountain by 4 p.m. to avoid walking in darkness.

On the peak just behind the Kobo-Daishi statue atop Shashingatake Cliff, another strange and striking sculpture faces west across the layered mountain ridges. It’s one of the best viewpoints on Mt. Tairyuji — from there you can often see the ropeway cars crossing high above the cedar-covered valley.

This bronze figure is called Yamasakimori 山さきもり, part of the “Sakimori” series by internationally acclaimed sculptor Masayuki Nagare 流政之 (1923–2018) from Takamatsu, Kagawa.

According to the Tairyuji Ropeway website:

“This is a bronze version of a guardian of nature, based on a mold carved from a sacred giant cedar of the T21 forests. The human-shaped form has a hollow center — the hollow holds life, or dreams,” said Nagare. The statue embodies his powerful wish for peace.

We passed the Shashingatake Cliff without stopping to visit the Kobo-Daishi statue this time — we planned to return here the next morning before descending via the Iwaya-michi trail.

At the fork where pilgrims usually turn left for Iwaya-michi, we continued right onto the Kitaji-michi 北地道 route.

Kitaji-michi Trail

In terms of distance, the Kitaji-michi 北地道 isn’t particularly long — just under 3 km. From there, it’s another 1.5 km of road walking to our lodge for the night, Sowaka. Easy enough, right? If this were a normal, well-maintained trail, I’d expect it to take about an hour and a half.

But I knew the reality. This trail is rough — and barely maintained.

Neither the Japanese nor the English Shikoku Pilgrimage walking guides include the Kitaji-michi. Few pilgrims or even hikers use it anymore. It runs mostly beneath the ropeway line and emerges on the far side of the mountain, opposite the direction toward T22.

For a time, this route was still used by villagers on that side of the mountain to visit T21. But once the ropeway opened, it quickly replaced Kitaji-michi as a faster, safer, and all-weather option. When no one walks a trail, no one maintains it — and soon nature reclaims it.

I had last walked Kitaji-michi six years earlier, when it was already rough and fading. I hadn’t returned since, but I could imagine what years of typhoons and heavy rains had done to it. It wouldn’t be an easy or quick descent.

We chose this route purely for curiosity — and because, for once, we had time. I’d walked it before, and we also had a GPS track to guide us. The trail has no red-and-white Shikoku Pilgrimage markers, so navigation is entirely your own.

We don’t recommend anyone attempt this route unless you’re an experienced hiker on rough terrain, have GPS navigation, and several spare hours. If your only reason is to walk a little-used trail, this one simply isn’t worth it.

Soon after starting down, we made a short detour to the wolf statues on a nearby cliff. Ropeway guides often point them out to passengers, explaining that the mountains here were once home to Japanese wolves — extinct since the early 20th century.

After returning from the cliff, we quickened our pace. The slope remained gradual, and the path wide enough for two to walk side by side. We passed another old limestone mining area, where rusted power poles still stood beside the trail. But I knew our easy walking would soon end.

Past the mine, the trail plunged sharply downward, narrowing to a faint track through dense native forest. The rest of the descent was steeper and increasingly eroded. Now deep under the canopy and on the shaded side of the ridge, dim light filtered through thick leaves. The quiet and lack of cell signal made me uneasy, even though I knew the route.

Still, I remembered there were a few open spots ahead where we could catch a signal. At the first of these, a small viewpoint, my phone came alive again. I called Sowaka.

When booking, I’d said we would check in at 5 p.m. It was now 4:40 — and we were still at least 2.5 km away and 400 meters above the lodge.

On a paved road, we’d cover that in half an hour. But on this steep, unmaintained slope, we had to move carefully. I told the Sowaka staff where we were, assured them we weren’t lost, and said we should arrive by 6 p.m.

When You’re Late for Your Planned Check-In

If you’re running late for your planned check-in time at a lodge along the Shikoku Pilgrimage, especially at small, family-run inns, make every effort to contact them — ideally by phone — to let them know you’ll be delayed.

Beyond Japan’s famous culture of punctuality, innkeepers will genuinely worry that you may be lost, especially if your route includes mountain trails. It’s not uncommon for owners or staff to drive out looking for missing guests or wait at the nearest trailhead until they appear.

NOTE: Unfortunately, no-shows by international pilgrims became a serious problem in the years leading up to the COVID border closure. Some accommodation owners, after repeated no-shows, became understandably hesitant to accept reservations from foreign walkers who couldn’t be reached by phone or email.Letting the inn know you’re safe and on your way spares them unnecessary worry and allows them to keep running their busy evening routines.

I’ve heard a few international pilgrims say they thought it was fine to walk through the dark and arrive around 8 or 9 p.m. No. Just — NO.

Pilgrims’ mornings start early, often by 7 a.m. or earlier. For small innkeepers, that means waking well before dawn to prepare breakfast, after cleaning the kitchen, dining area, and bathrooms from the night before. They depend on the evening hours for rest and preparation. A guest arriving at 9 p.m. forces them to stay up, delays their cleanup, and cuts into their already short rest time.

A simple call is not just courtesy — it’s respect for the people who take care of you on the pilgrimage.So, letting them know you are not lost and surely coming to stay at their place makes them spend time worrying about you and instead use the time to run their inn during the busiest time of the day.

I have heard from some international pilgrims/hikers said they thought it was no problem to walk late evening through the dark and get to their accommodations at 8 or 9 p.m. No. Just, NO.

Pilgrims’ morning is early. Many of them want to start walking around seven or even earlier. That means the owner of small inns has to wake up much earlier than that to cook breakfast for them after they served dinner, clean up the kitchen, dining room, and bathroom, then rush to bed to wake up early the following day. A guest arriving at 9 pm causes them to stay up and wait, pushing all the cleaning up and preparation time for the next day back to less rest time.

The Lower Part of the Kitaji-michi Trail — Steep, Rough, and Rewarding

Before long, we discovered our cautious time estimate had been right — the descent took far longer than it looked on the map.

As is often the case, the lower sections near the foot of the mountain were even rougher. Without the GPS track, we would have struggled to find the route. Parts of the trail had been washed out by runoff from heavy rains and minor landslides.

Thick layers of fallen leaves from the previous autumn still carpeted the steep slope, making every step slippery. We moved carefully, trying not to slide down the hillside.

Near the bottom, the mountain gave way to man-planted cedar forests that blocked nearly all sunlight. The air was clammy and dim as we stumbled over piles of branches scattered across the path — every thirty seconds, another obstacle.

When we finally stepped out of the trees, I was startled by how bright it still was outside. The sky glowed a clear blue, as if it were midday. Passing a few houses, we left the mountain behind and entered Kitaji hamlet.

Across the curving Nakagawa River, sunlight reflected off the rice paddies. The ropeway station stood visible on the far bank. our lodge, Sowaka, was just behind it — so close, yet we had to circle around and cross the wide red bridge spanning the river.

Now back on flat ground, our pace quickened. The evening light made the river and fields glow in soft colors as we walked the final 1.5 km.

At 5:57 p.m., we arrived at Sowaka — just under the wire for our 6:00 check-in. Through the open dining-room door, we saw other guests already eating dinner.

Sowaka had always been one of my favorite places, and it didn’t disappoint. our room looked newly renovated; the tatami mats still carried their fresh, grassy scent, and the walls gleamed with new paint.

We quickly gathered our laundry, loaded the washing machine, and hurried to dinner before the dining room closed.

Dinner was comforting home-style food, like what you’d eat in an ordinary Japanese household — not the lavish tempura-and-sushi spreads served at some inns. We actually prefer this simpler style.

For breakfast, guests can choose between eating at Sowaka or taking onigiri (rice balls) for an early departure. Knowing the next day would be long, we ordered our rice balls in advance while eating dinner. Erik, not much of a rice fan, planned to rely on his nutrition bars, so I claimed all four onigiri as my breakfast and lunch — a perfect plan.

We ended our long, tough day in Sowaka’s large public bath. That night, I had the women’s bath entirely to myself. Soaking in the hot water, I could feel the fatigue leaving my legs — the perfect way to restore strength for tomorrow.

UPDATE: Sadly, Sowaka closed permanently at the end of 2022.

In 2024 — The Long-Awaited Return of our Lifesaver!

In the summer of 2024, with a new owner and team, Iyashi-tei KoKU いやし亭・心空 soft-opened in the same beloved location as Sowaka — officially reopening in full operation that autumn.

Major parts of the building were beautifully renovated:

- 1st floor: Smaller rooms (including three with Western-style beds) suitable for solo guests or couples.

- 2nd floor: Larger rooms for those wanting more space.

Booking options:

By phone: 0884-63-0032

Online booking via KOKU’s official website and major booking sites

- Room rates are per person.

- Rate differences between phone and online bookings reflect processing fees.

- Rates are subject to change.

A lunchtime restaurant is open most Wednesdays and Weekends — check their instagram for dates and menu. A seasoned former hotel chef will be cooking at KoKU.

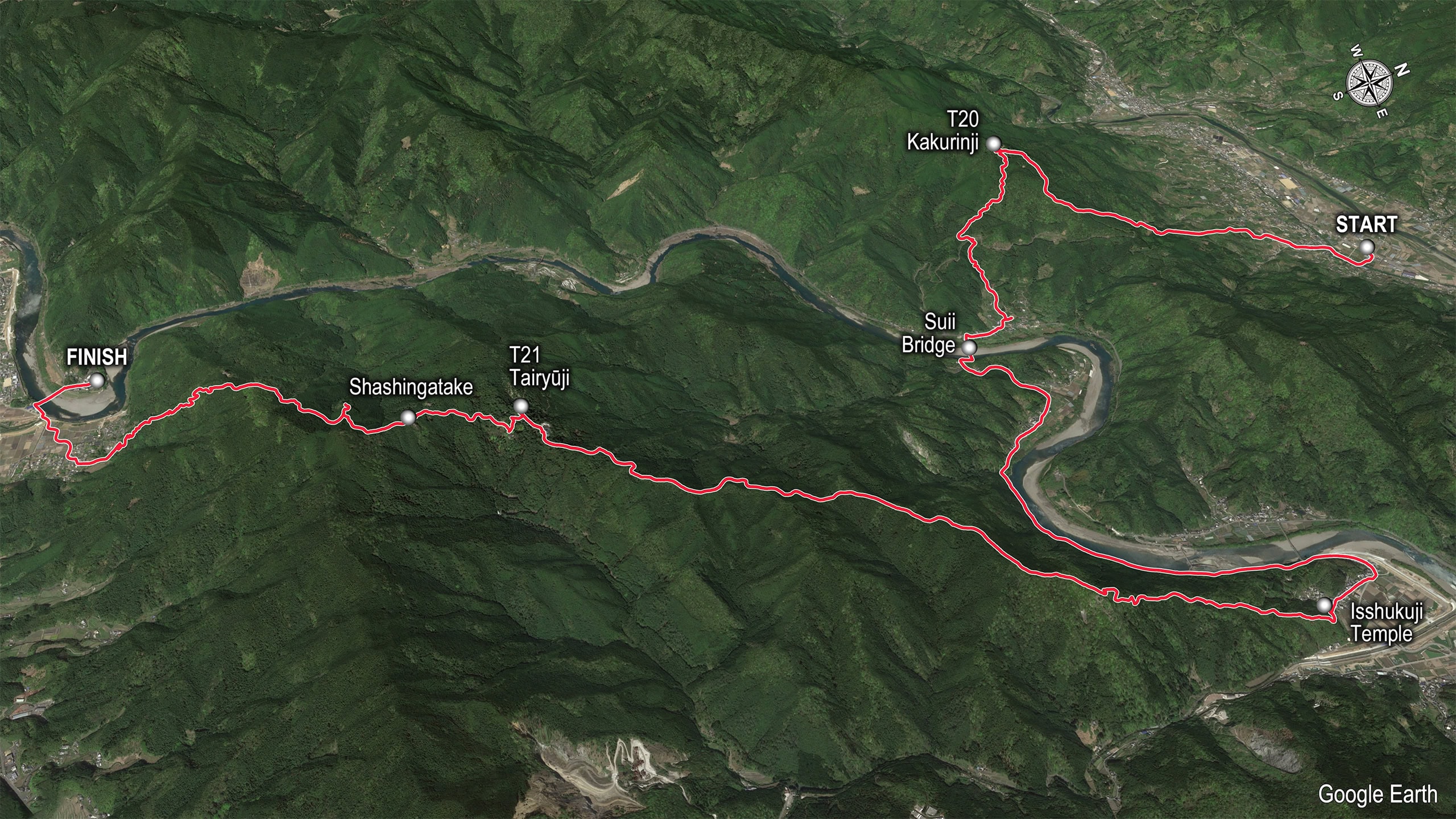

Shikoku Pilgrimage – Day 20

| Start | Michi-no-eki Hinanosato |

| Distance | 20.4 km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 1414 m / 1391 m |

| Finish | SOWAKA |

| Time | 10 h 18 m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 549 m / 25 m |

| Visited Temples/POI | T20, T21 |

Route Data

The Shikoku Pilgrimage 2022 – Vol.1: late April to mid – June 2022

Comments