The excellent view through the windows of our room at Zuiko was even better this morning.

The seawater was lighter blue and more transparent, calmly shimmering under the morning sun. The rain clouds and cold wind had gone.

We slept well last night as Zuiko was pretty quiet inside and outside. Surprisingly, though, Zuiko’s guest rooms seemed fully occupied, we could hardly see others. We had both our dinner and breakfast at the restaurant area and had the space all to ourselves.

All other guests stayed the longer term for their work at construction sites around the Oshika Peninsula and had discounted deals with more casual services. So, their dinners and breakfasts were placed on a shelf in the hallway for self-service. When the workers returned from work, they picked up their plates, ate in their rooms, and then left empty plates on the shelf. After that, everybody seemed relaxed in their room and did not stay up late.

We appreciated the quiet night.

The former Momonoura Elementary School site

When we checked out around a quarter to nine, the owners of Zuiko followed us outside to see us off.

They expected us to go to the left in the direction of the neck of the Oshika Peninsula, so they looked a bit puzzled when we pointed right to go back the way we came from last evening.

“A short down from here along this road, there should be a forest path to go down closer to the sea. That is the MCT route.”

“Oh! I see,” smiled Mrs. Zuiko. “That was the path I would always walk to my elementary school.”

Good, we got a strong confirmation from a local, as the official MCT map book showed a former elementary school remains along the forest path.

Walking back on the Prefectural Route (highway) No. 2 (R-2) about 700 meters, we returned to the point we passed last evening, where a sideway went down into woods.

The gravel road covered with grass and fallen leaves soon turned a narrow forest path through Japanese cedar trees, gradually going down.

Soon, we spotted two short stone pillars standing between trees. One of them had the old school name, Momonoura Elementary School 桃浦小学校, inscribed on it. Sadly, these old school gate stones were almost the only trace of the school against my expectations for an old but kept school building or something to keep the memory. The school ground was empty, and trees and plants quietly buried the place into oblivion.

Facing the school gate, two stone Buddha images, one of them was Jizo, the guardian Buddha of children, were kept in a tiny rustic wall-less temple.

The standing-posed Jizo had stumbled for some reason, and the front fence barely kept him from bumping into stone tiles in front of the temple. Erik gave him a quick reposition back to standing straight again before we continued on our way.

Hamagurihama

Soothing air filled the cedar forest path, and morning sunlight came through the trees, making shining spots on the path and stream water. It was a good walk to start the day.

At one point, we were very close to the sea level, and there was a hidden small sand and pebble beach with amazingly clear and beautiful green water. Though we could have easily walked down to the beach, we chose not to as we were just at the beginning of the long hike, including crossing a big mountain.

The only one-kilometer forest path soon connected to a quiet paved road that led us to, of course, another fishery hamlet called Hamagurihama 蛤浜.

There, for a short period, we lost our way. There are no MCT route signs around. The map book showed we were supposed to go up to rejoin R-2, and yes, there were concrete stairs in front of us. But they really looked like private paths to houses as all houses in this tiny hamlet stood on higher grounds.

We did have a GPX file we downloaded from the official MCT website and installed it into our hiking navigation devices. The route line looked like it was going straight into one of the houses.

If this were the case on the Shikoku Pilgrimage, we would just go even if it looked like someone’s front yard because that happens quite often on the Shikoku routes, which were formed over a thousand years of its history. But we were not so sure about nearly trespassing on private properties was locally accepted on the MCT, a relatively new long-distance trail. Had so-called trail town culture evolved in all neighborhoods along the way?

After walking around one more time to make sure there was no other path or stairs to go up the hill behind the hamlet, we made up our minds and went up the concrete steps in the direction of the GPS track line.

At the top of the stairs, an old house blocked our way, and we wondered which side of the house was the more unsuspicious trespassing. Then, through the window, I saw a young lady working inside the kitchen, not noticing us standing there.

I tapped the window to get her attention, and she came out. Much to our relief, she didn’t look surprised by strangers standing in front of the kitchen window.

Later, we found, on Google Maps, this house was the Hamaguridou はまぐり堂 shown on the MCT map book. I had incorrectly assumed, from its name, that it should have been a temple or shrine, but this place was actually a cafe, which opens only on Saturdays.

She sympathetically smiled and pointed to a space just outside of the kitchen.

“You are welcome to go through here to another stairs behind our house. This is the MCT route.”

Without her help, we could not believe this path was indeed the route. That was how we felt when we saw the steps behind Hamaguridou, looking shockingly casual and private with no MCT logo or sign.

After that, the path became more public-road-looking concrete stairs with handrails, which must be the evacuation route for residents.

After long, steep stairs, we finally came out to R-2.

Interestingly, a big tree house stood by the exit, next to a roofed concrete shelter for the Hamagurihama bus stop. The tree house and the wooden ladders looked pretty solid, so we went up to enjoy the feeling of Alice in Wonderland.

We had no idea why and who built the tree house there, but later, I found a meaningful story on the Hamaguridou website.

From the tree house at the Hamagurihama bus stop, the MCT route follows R-2 for a while. We knew quite a long tunnel was awaiting us right around the corner. Yesterday’s horrifying experience on sidewalk-less R-2 traumatized us enough to be pessimistic. How could the tunnel, which is still a part of R-2, be an exception?

But a delightfully unexpected thing happened. After a short walk on still shoulder-less R-2 through cedar trees, wide sidewalks suddenly appeared, not only on one side but both sides of the road!

Furthermore, they kept going into the tunnel. Yesterday, a mere 30cm of space on a road shoulder that our shoes could barely fit in on a road shoulder. Now, in the Kazekoshi Tunnel 風越トンネル, we were walking on a well-constructed flat sidewalk that even a car could easily run on. It was also very bright inside the tunnel.

The amazing sidewalks continued beyond the tunnel, and R-2 became a gradually descending road bridge crossing a valley.

We were approaching the point of concern for today that had troubled my hike plan for the last few days…

The south shore road of Mangokuura

Let me rewind to the breakfast table at Zuiko this morning.

“…Wait, a road closure for construction?” the owners of Zuiko echoed, with the faces of pure confusion.

At the time of our MCT thru-hike in spring 2021, a big part of the original MCT route we would walk on this day was supposed to be “closed” for a long term due to a large rebuilding construction, according to the MCT website. That was the part on a road running along the south shore of Mangokuura 万石浦.

The blocked part was about 3.5 kilometers, between a road branch from R-2 and the Yamahon seafood factory in Harinohama village. The problem was that there was no other alternate sideway or village path to connect these two points, and the MCT website directed hikers to the tentative alternate route: stay on R-2 until crossing the Mangoku bridge to walk on the National Route (highway) No.398 (R-398) on the north side of Mangokuura, or go to Watanoha station to take a train that mostly parallels R-398 towards Onagawa town.

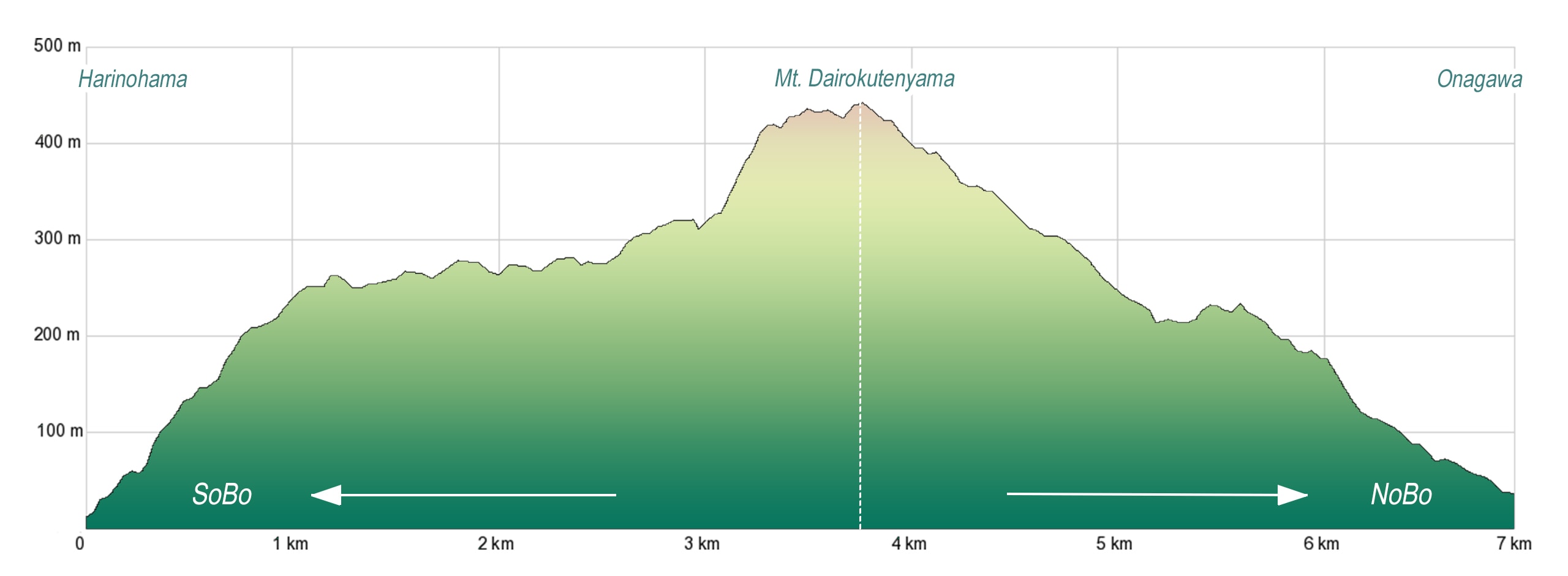

For Northbound hikers like us, this road closure part was just before Mt. Dairokutenyama 大六天山, one of a few decent mountain climbs we could have in Miyagi prefecture part of the MCT.

At this early stage of our 50 days of the MCT thru-hike, still only Day 12, I could not let go of my regular obsession to follow “precisely” the route line as it was drawn in the route map.

Like I did to tackle the hardest to reach Kinkasan Island, I searched other Japanese MCT hikers’ latest blogs and hiking logs to see what they did for this part and the current construction status.

I knew very well how the infamous overly-cautious Japanese municipalities’ bureaucratic system so quickly and mindlessly LOVE putting the “road closed” signs on trails, especially the fewer traffic ones in the mountains and remote areas. As someone who had been involved in a local volunteer trail-clearing group and walked various trails in Japan, I had seen road-closed signs left untouched for years on the trails that didn’t have noticeable problems for walking. Also, as a resident of a remote area, I know those large-scale, long-term construction projects were often paused and left alone for a while.

It was possible that the public authority in charge of the road construction just kept telling the MCT trail center the road was still closed no matter how the actual condition was — because it was the easiest and “the safest.”

I also discovered a house with actual residents within a few hundred meters from this side’s road closure point on a map. Then, the road to their house could not be fully closed; no authority could ban them from returning to their home. More and more photos and blogs suggested the construction was almost done.

I concluded that if we could reach the residential house via a mountain forestry path or something, we should be fine to walk the rest of the closed part.

On a larger-scaled topographic map, I did see some dotted lines over the Kazekoshi tunnel, but the tricky reality is that dotted lines on maps don’t always equate to maintained walkable paths. Then, the best way I always go is — to ask the locals.

So, I was asking the Zuiko owners if those dotted lines were active forestry roads that enabled us to skip the possibly a few hundred meters of road closure. But they reacted to the word of road closure rather than the possible forestry roads.

“Road closure? That’s weird. Wasn’t the new road already done?”

— Oh, that sounds REALLY interesting.

“I think the construction has something to do with a new bridge or tunnel.”

“Bridge? Then, the bridge construction stopped for long. Nothing is going on there for a while.” “Didn’t we drive through the new road sometime before…”

So, here we were at the fork where the original MCT route sidetracked from R-2.

Five minutes later, we were walking on a perfectly done, beautiful new road along the south shoreline of Lake Mangokuura. We saw nothing; no construction materials, machines, or workers at the supposedly under-construction area. Only two gigantic high concrete bridge pillars without girders and decks stood alone.

After enjoying walking the deserted new road that had some pretty good viewpoints of beautiful Mangokuura for a while, we came across a roadside sign that said the construction was done and that the new road was open to the house of the Fujiyamas…my presumption was correct. But it also noted that further from the Fujiyama house was still under construction and blocked, which was the no-construction-going-on part we just walked through…

We reached the other end of the supposed road closure part in front of the Yamahon Seafood factory in Harinohama 針浜 village.

Mt. Dairokutenyama

We took a short break at a vending machine by the factory that sold not only drinks (both hot and cold) but also potato chips and chocolates. Harinohama would only be 1.5km away from the base of Oshika Peninsula if we kept walking straight along the Manganura shore. But we were turning backward to climb up and down Mt. Dairokutenyama, the second-highest mountain in the Oshika Peninsula, standing high behind Harinohama village.

It is a mysterious coincidence that the highest mountain in the Oshika Peninsula, Mt. Kinkasan, stands strong at the southernmost top of the peninsula, and the second highest mountain guards its base.

There are no supply points for food and water for the next 10 kilometers of the mountain trail. We bought more drinks from the vending machine by the factory and another shortly down the same street to ensure we had more than enough water to go through the mountain.

We quickly passed the houses and empty farmlands and followed the MCT route signs that led us into a cedar forest.

That first part through the forest was narrow and dim under thick trees in the shade of the mountain. It was also a bit rough trail with many branches covering the surface and some fallen trees blocking the way.

After the initial struggle, however, we came out of the cedar trees’ shade and found ourselves standing on a much wider and brighter logging road. The higher parts of the mountain had significantly fewer trees. Most parts were nearly bold, so we had a great view of Lake Mangokuura and its signature products, sea farms of oysters.

With the brighter conditions around us now, Erik suddenly stopped me and pointed to my hiking pants around the back of my right knee. — A LEECH!

Erik immediately picked it up and threw it away into the sky. Thankfully, it was just about to start sucking my blood, so my leg was not bleeding.

We frantically searched for any more ones all over our pants, tucked them up to check on the socks and bare legs, and took off our shoes to see the insides. The traumatic leech events on the Iseji route of Kumano Kodo a half year ago were enough, and hopefully never be again.

“Ah ha!” Erik also found a tiny one on his sock, which was, of course, followed by another flying leech into the sky.

We got a bit paranoid just like after the Kumano Kodo cases happened. Anytime we felt slight irritation or pinching sensation — some of them could be just imaginations — around ankles and lower legs, we stopped and pulled up the hems of our pants to check that no evil blood-sucker was hiding there. It did slow our walking for a while.

Now we understand, at the very final moment before we got out of the Oshika Peninsula, why the tourist information center inside the Whale Town Oshika at Ayukawa Port had leech sprays on sale and visibly cautioned visitors that Oshika is a habitat of leeches.

Thankfully, other leeches must have learned lessons from two flying leeches in the sky, and no one dared to challenge us.

Soon, we reached a ridge line and started traversing. All trees were cut down, and continuous clearings were made on the mountain shoulders, though they provided spectacular, nearly 360-degree views. We could see downtown Ishinomaki city beyond the big Mangokuura lagoon. Only three days ago, our ferry to the cat island left the port there.

We passed a few transmission towers, which might be a partial reason why the top areas of the mountain were so clear and plantless. The trail we were walking on might have been built primarily by a power company to maintain the towers. Aside from the MCT official trail markers, some handmade trail signs were placed along the route.

Most parts of the ridgeline traverse were nearly flat and easy to walk until the last steep uphill with a long flight of stairs built with the black lightweight carbon plates typically seen on the transmission tower maintenance paths.

Surprisingly, the MCT route line misses the peak of Mt. Dairokutenyama. When our mountain trail met a concrete paved forest road, a trail sign directed MCT hikers to follow another path to go down immediately from that point.

This sudden concrete road gave us a clue to our question about the wheel tracks of motorcycles or bikes on dirt we saw along the ridge line. Probably some off-road riders entered the mountain via this power maintenance road.

A short and quick detour on the concrete road should take us to the mountain’s highest point. Let’s check it out.

The mysterious name of the mountain had made me expect something remarkable at the peak.

Dairokutenyam: “dai” = -th, “roku” = six, “ten” = sky or the heavenly world where gods and buddhas live, and “yama” = a mountain. So, the mountain’s name means the sixth heaven, and it is a Buddhist terminology.

From what I tried to study from the information online about the human world and heaven concept in Buddhism, it consists of layers of different worlds like a piecrust. Let’s say if I try to compare the image of it to a high-rise building, Dairokuten is on the sixth floor, and the heavenly world is from the sixth floor and above. Though the top floor is nirvana, I could not figure out exactly how many floors the building has. At least 28th or more. Probably depending on one’s interpretation, which may be why Japanese Buddhism has so many different sects… We humans live on the 5th floor, by the way.

For some reason, the leader of the sixth heaven is a devil king called Dairokuten-maou. Once upon a time, fishermen in the area enshrined the devil king, who is also a god (confusing, I know), at the peak to pray for happiness, like living in heaven. The mountain’s name also immediately reminded me of the most famous historical person in all of Japanese history, Nobunaga Oda, whose nickname was the Sixth heaven’s devil king.

Anyway, at least to me, Mt. Dairokutenyama sounded as holy as Koyasan or other most well-known sacred mountains in Japan. So far, my honest impression of the mountain was not so positive, mainly due to the too much treelessness around the top area and leeches. My inflated expectations had been shrinking as we hiked up.

To my absolute disappointment, there was nothing but a giant radio tower and its control facility building at the peak of Mt. Dairokutenyama. The stone block for the triangulation point (439.1m) and a simple wooden sign for Mt. Dairokutenyama summit sat in the middle of a small clearing next to the radio facility, surrounded by thick walls of trees. So, there were not even views from there…

There seemed to be an old shrine on another, a shorter peak area with better views that was good for taking a break. But we had to save it for next time, as it was almost 2 p.m.

Our way down gave us more variety of feelings than the way up.

The scenic Rias coastline along the Pacific Ocean side of the Tohoku region stretches from Oshika Peninsula up north to Kuji City, Iwate. We enjoyed the first glimpse of the spectacular sawtooth terrain and blue ocean while walking down the shoulder of the mountain.

Then, the trail got super narrower, traversing a hillside. The traverse required me to take cautious steps forward because the slope was so steep, almost drop-off, and bare, like a ski field for advanced-level skiers. The traverse trail looked narrow and fragile, almost like a wildlife path.

Though, during the last ten days of hiking, since we started from the south terminus, there were a few parts of mountain trails that we needed to be extra careful about, there was always something we could hold. Having no trees that I could clutch in case my feet slipped and slid down probably contributed a lot to making the trail look more treacherous than it actually was. Anyhow, I could tell heights phobias would not feel comfortable walking through this one.

We appreciated that the earth and grass on the slope were dry; otherwise, we would hesitate to cross.

We underestimated the hiking down. Its distance and time needed were much longer, and the terrain was more challenging than up.

We came out to an asphalt car road, not knowing this was the same Cobalt Line near its other end. Within a few dozens meters from our optimistic expectation of speeding up our walk along the paved road, an MCT trail maker welcomed us into earthen stairs on the other side.

With the sunken spirits and heavier legs, we had to walk upwards again to go over one more big bump on a ridge line.

But we finally entered the Japanese cedar tree plantation area, typically around the foothills, and knew our long way down was coming to an end soon.

The exit of the trail was an abandoned house and its backyard. A cluster of oriental paperbush, Mitsumata in Japanese, quietly had delicate yellow and white flowers in full bloom.

As we were further away from the mountain on a newly built paved road, we heard announcements from the community broadcast service speakers. It was about a regular vermin control deer hunting and temporary restriction to enter the area… tomorrow… in Mt. Dairokutenyama!?

Luckily, we unknowingly managed to miss it.

Onagawa Port was a big fishery port. We spotted a large fish market beyond the harbor on the opposite side from where we came out. It was nearly sunset, so the port area was deserted, and various fishery ships were quietly bobbing—time to farewell to Oshika Peninsula.

We arrived at Onagawa Town 女川町 now.

Day 20 – MCT

| Start | Zuiko |

| Distance | 18.7km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 673m/720m |

| Finish | Onagawa Station |

| Time | 7h 42m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 442m/ 0m |

Route Data

The Michinoku Coastal Trail Thru-hike: Late March − Mid-May 2021

- The first and most reliable information source about MCT is the official website

- For updates on detours, route changes, and trail closures on the MCT route

- Get the MCT Official Hiking Map Books

- Download the route GPS data provided by MCT Trail Club

- MCT hiking challengers/alumni registration

Comments