The Power of Hare-Onna

We’ve been lucky with the weather since Day 1.

Today was supposed to be rainy again, but when we woke up and opened the hotel curtains, the sun was already high and blazing. It even looked hot outside.

In Japan, we call someone who always seems to get good weather when they go out a hare-onna / hare-otoko 晴れ女/晴れ男. (Hare means clear weather; onna is woman; otoko is man.) By that definition, I must be a hare-onna: most of my past hikes have been sunny or at least just cloudy—even in seasons that are “supposed” to be wet.

When I walked my first Shikoku Pilgrimage in fall 2015, I had only a handful of rainy days out of sixty-five—and most of those landed on rest days. Shikoku is usually wetter than many other regions, and early fall lines up with typhoon season. But that autumn was unusually dry, nearly drought-level. Apparently my hare-onna powers were working a little too well.

Back to the Former Watari Castle Site

Last night we stayed at Watari Onsen Torino Umi わたり温泉鳥の海. The big public bath is open to day visitors until 8 p.m.; after that it’s for hotel guests only. We went just before bed, and both the women’s and men’s sides were totally empty—ours alone. Best kind of recovery after a long day in the mountains. It was a Monday night, off-season, and mid-COVID; we wouldn’t have been surprised if we were the only guests in the whole place.

After checking out, I called the taxi number from yesterday. A cab showed up right away, and by 8 a.m. we were back at the same grocery store beside the former castle site, where we rejoined the MCT.

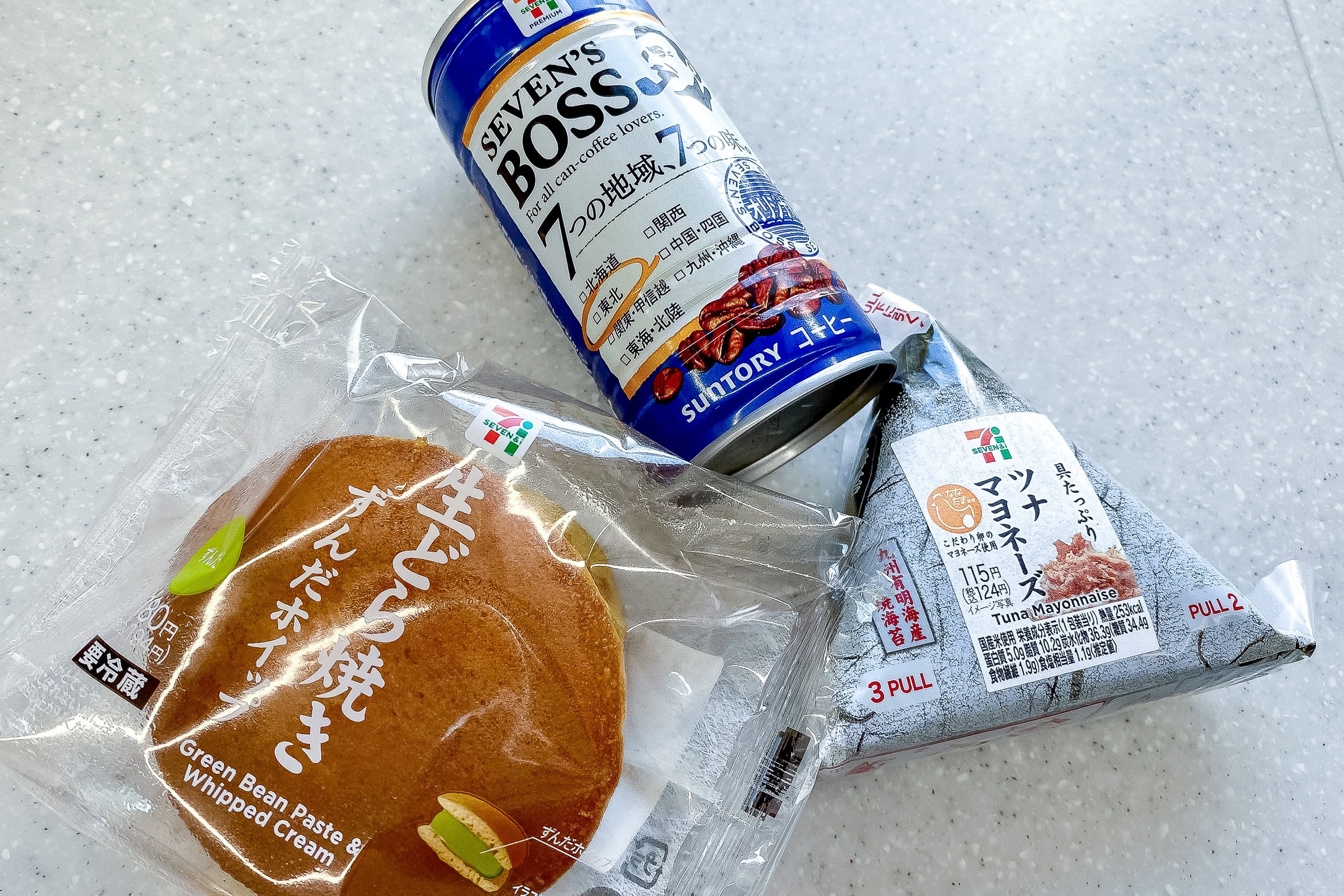

The store didn’t open until 9 a.m., so we set off, and soon found a convenience store where we grabbed light breakfasts—morning coffee for me and hot milk tea for Erik.

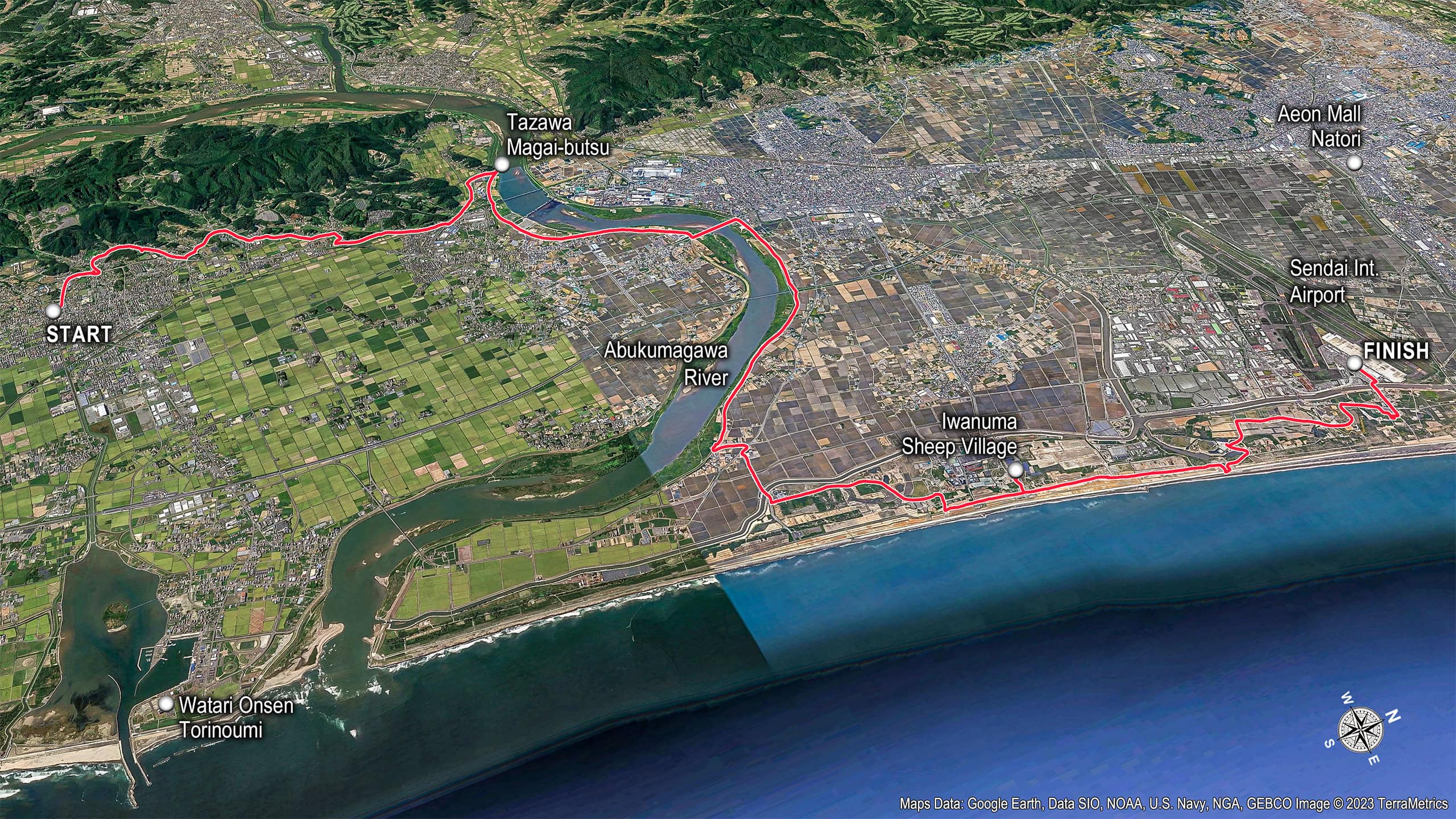

According to the MCT route map, today would be mostly flat and heading into busier areas.

First, though, we needed to walk to yesterday’s original goal—4 km from the grocery store—so with that add-on, we expected about 24 km total. Not that long. Today should be easy… That’s how chillaxed we were then.

The route began through a quiet neighborhood where small vegetable plots sat between houses. We were surprised to pass a little olive orchard. In our minds, olives belong to arid, sun-soaked Mediterranean hillsides; Tohoku is colder, with heavy winter snow. How do olives survive here? Or are they tougher than we thought?

We passed several local elders on their morning walks. As in Shikoku, we greeted each person with a “konnichiwa” or “ohayo gozaimasu.” Every time, a smile and a gentle “good morning” came back to us. us.

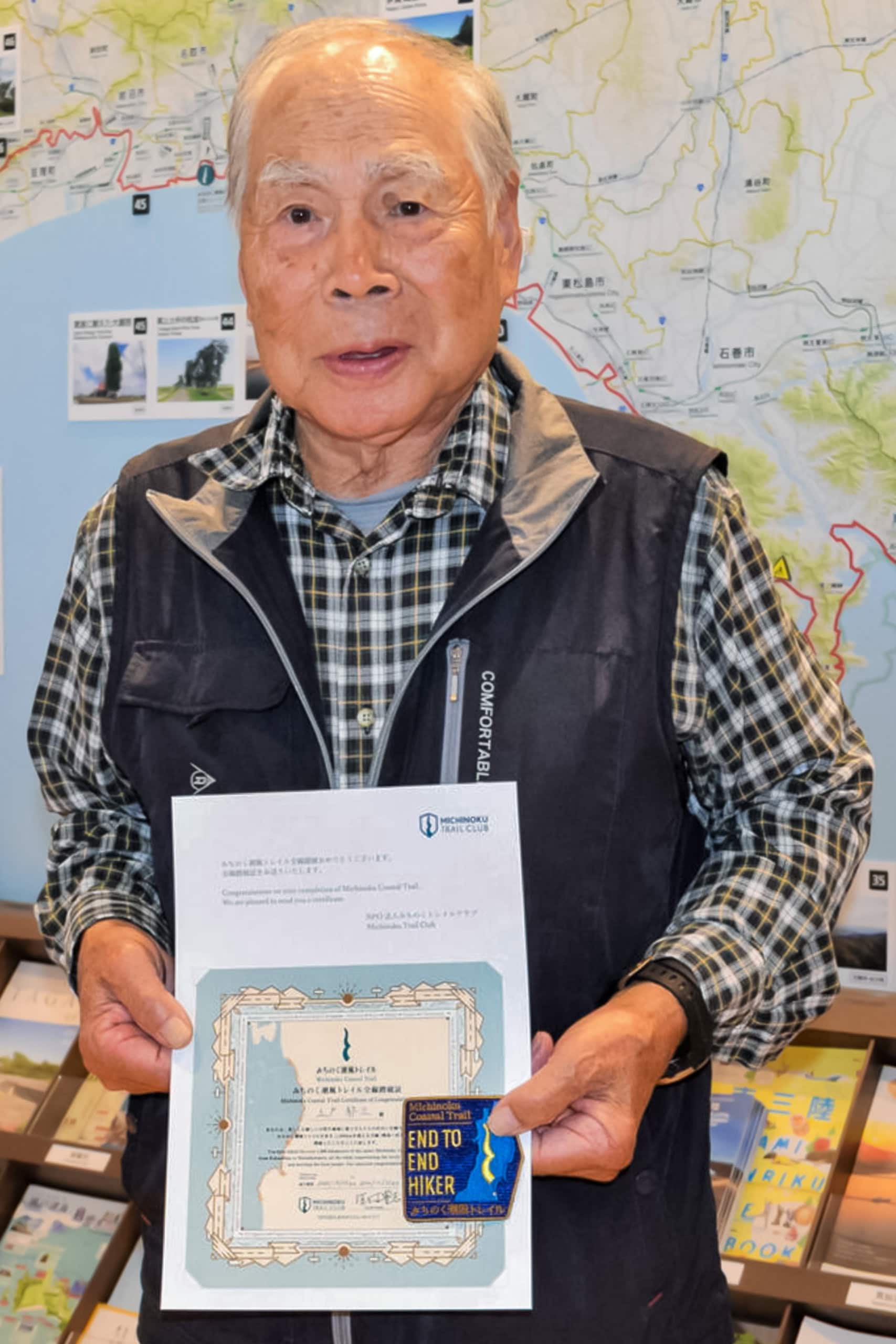

The oldest MCT thru-hiker

Then, a friendly-looking grandpa came walking his dog.

“Are you two walking the Michinoku Shiokaze Trail みちのく潮風トレイル?” he asked. (That’s the Japanese name of the MCT.)

He told us that he’d been walking the MCT as a series of section hikes, northbound from the southern trailhead in Soma City 相馬市, and had already made it as far as Kesennuma City 気仙沼市. When we said we were northbound too and that it had been four days since we started, he looked amazed. His eyes widened even more when he heard our plan — to walk the entire 1,000 kilometers in one go, over 50 days, averaging 25 to 30 kilometers a day.

He laughed and said he was too old for that kind of distance (later we learned he was 85 at the time), so instead he was hiking the MCT in shorter day trips, steadily moving north bit by bit. His family fully supported him, driving him to each trailhead and picking him up at the end of the day. Sometimes his grandson joined him, especially for the mountain sections.

“One day,” he said, smiling, “I’ll reach the northern trailhead in Aomori. That’s my dream — my reason to keep going.”

“Then maybe we’ll see you again somewhere up north on one of your next walks,” we said.

He was already so far ahead of us that the thought didn’t seem impossible at all.

He Became the Oldest MCT Thru-Hiker

On October 13, 2022, that same grandpa, Ikuzo Tsuchido, completed the entire trail — becoming the oldest MCT thru-hiker at age 87!

According to a Kahoku Shinpo news article, he was inspired by seeing MCT hikers pass in front of his home. In October 2020, he retired from his business and decided to start walking the trail himself. He covered 10 to 20 kilometers each time, finishing all sections in 73 hiking days.

He had started hiking mountains at 65 and even climbed Mt. Fuji at 80. His next dream? To climb it again when he turns 90.

We said goodbye to the MCT-walker grandpa and his polite little dog, who had quietly waited by his side the entire time we talked. Not long after that, we passed Okuma Station 逢隈駅 — the goal we’d originally planned to reach yesterday.

The station had a nice waiting room and some vending machines. We dropped by for a short coffee/tea break, not realizing how precious this opportunity was.

Who knew these vending machines would be the last before so long – as distant as 15km until we could find the next one…

Along the Abukuma River

Eventually we reached the wide Abukumagawa 阿武隈川.

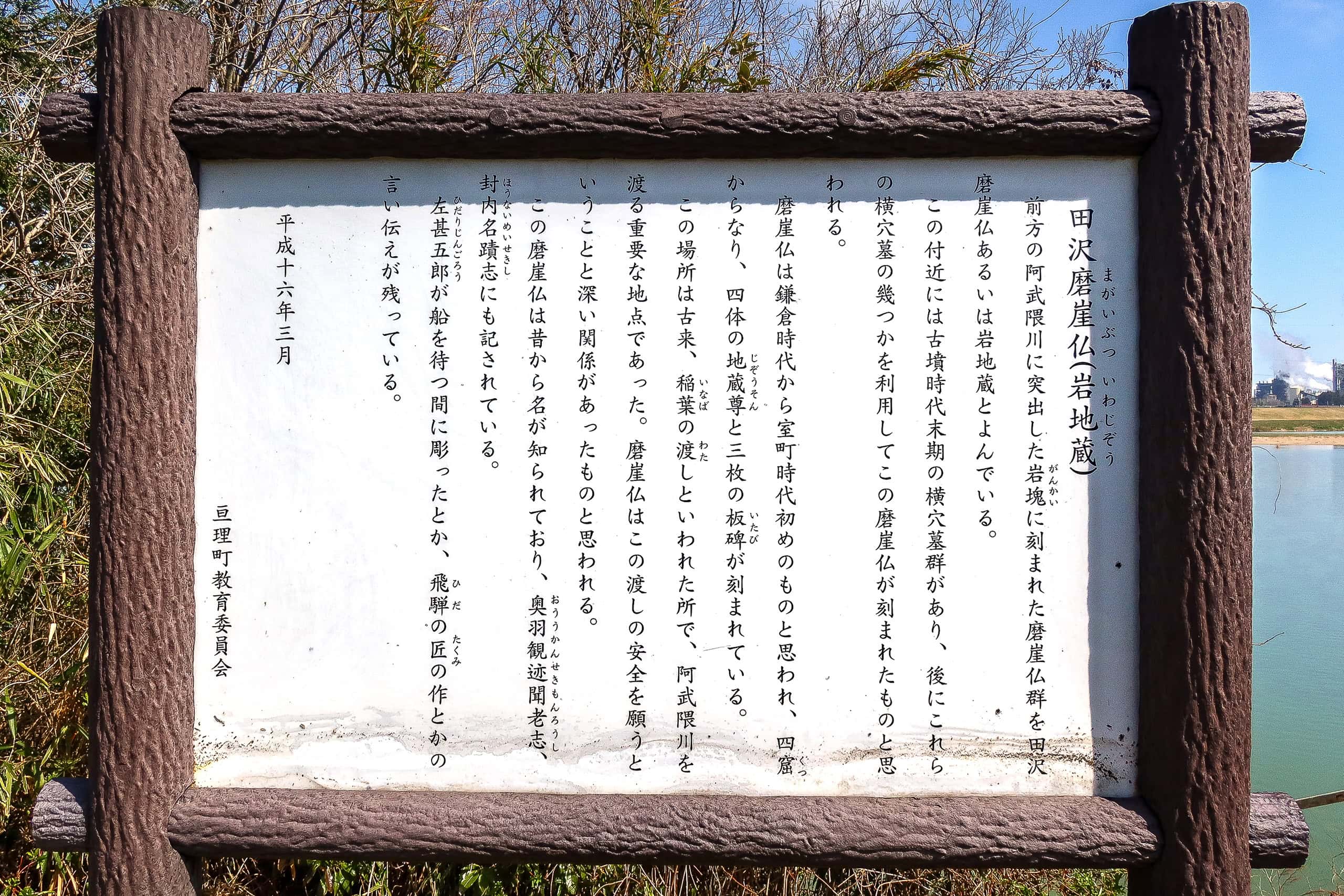

Climbing up onto the one-lane road along the riverbank, we found a massive boulder standing in the water, and on the rock faces around it: Tazawa Magaibutsu 田沢磨崖仏 — centuries-old Buddha images carved deep into the stone recesses.

Nearly half of today’s walk would be on these pedestrians-and-bikes-only riverbank roads: asphalt, arrow-straight, and super flat. The good news: no cars to dodge. The bad news: no shade to block the sun or the heat. At least the route would thread past a few local sights — like the rock-carved Buddhas we’d just seen — to keep things from getting too monotonous.

By midday the sky was a flawless blue. To the west, the snow-covered Zao mountains 蔵王連峰 stood tall and crisp. In the morning their upper slopes had hidden behind heavy cloud, but the clouds finally burned away, and Zao’s ridges appeared in full, framed neatly beyond a big watergate bridge over the Abukumagawa.

From the very start, the sun felt over-energetic today — as if determined to prove it could turn the northlands into summer all by itself.

I walked on the grassy strip beside the road whenever I could, hunting for softer ground instead of the hard, heat-soaked pavement that loves to make blisters. Compared with yesterday’s cooler weather, my foot pain came back much faster on this surface.

After about three kilometers on the south bank, we reached the very busy Abukumabashi 阿武隈橋.

Halfway across, we stepped over the municipal border — out of Watari Town 亘理町 and into Iwanuma City 岩沼市.

Iwanuma Bike Road – Sun, Concrete, and and Wuthering Heights

From the bridge, the busy main road stretched straight into the city center. In the distance we could see a parade of big roadside signs—national chain restaurants and shops on both sides—very tempting.

But, to our disappointment, the MCT didn’t head that way. It turned right, back onto a narrow paved lane along the opposite riverbank.

With slightly frowny faces and mixed feelings, we kept to the painfully hot, concrete-paved pedestrian/bike road, walking farther and farther away from the shopping area.

We still held out a tiny hope for bathrooms and vending machines ahead. Several road signs promised a cyclists’ rest area a few kilometers away.

…Sadly, the “rest area” turned out to be a table and benches under a small square roof. No bathroom. Our legs suddenly felt heavier. We took a short break; Erik carefully re-applied sunscreen to his face and neck.

Yesterday we’d spent most of the day in shade—under mountain trees and a cloudy sky—and this morning Erik had put on more sunscreen than usual. Even so, his face and neck were already bright red. Today he wore a UV-protection cap and kept adding sunscreen to keep things from getting worse.

I put more sunscreen on my face too. I learned the hard way how harsh Japan’s spring sun can be: as a child, I burned my face at a school sports day. Parts of my cheeks were literally singed.

My light breakfast—one rice ball and a small cake—had long since disappeared, and my stomach felt empty. Luckily I always keep a few candy packs in my backpack for emergency calories. I can usually go a long time without water, even in heat, but we still started wondering: how long until we finally meet our dearest friend again—the vending machine?

Erik always carries a Katadyn BeFree, a UL water filter in a collapsible flask, so we can get drinking water from natural sources or public bathroom taps in a pinch. And today, we were walking right beside water almost the entire time. Dehydration wasn’t the worry. Still—we missed vending machines.

We were now heading toward the river mouth. Far off to our right, the line of mountains we’d traversed yesterday sat along the horizon. To our left, vast empty farmlands spread out, with the occasional farmhouse nestled behind thick windbreak trees and hedges.

Finally, we reached the point where the MCT route left the long, monotonous riverbank road. There stood an old shrine, Nichigetsu-do 日月堂 — once swept away by the earthquake and tsunami ten years ago, but lovingly rebuilt by the local villagers.

Lining both sides of the path behind the shrine gate were several large stone monuments of different shapes. One was a flat stone covered with engraved letters. An information board explained that it had been erected ninety years ago to honor the “filial devotion” of a villager who’d been rewarded by the regional lord in 1773. His father, the inscription said, had also been an honest, kind man respected by the community.

From there, we left the riverbank and followed a narrow road cutting across the edge of the farmlands. After passing a couple of houses, we spotted a small prefabricated building on what used to be a residential lot. Our expectations instantly spiked — and YES! Something long-awaited gleamed in front of us: a vending machine!

The building looked like a temporary office for a construction company, and a few workers were coming and going as we — two total strangers, one of them unusually tall — made a beeline for the machine and chugged down bottles of tea, coffee, and sports drink right by their entrance. The workers seemed totally unfazed, maybe even slightly amused at the sight.

These makeshift construction-site offices have become our unexpected saviors while hiking in Japan. They nearly always have vending machines meant for staff, but hikers like us depend on them. Whether tucked away in the deep mountains or hidden along remote coastal roads, they appear like miracles in the unlikeliest places.

With an extra bottle of cold green tea in my backpack pocket, I felt recharged — and confident again that I could finish today’s long walk.

Now the village road we were following curved toward the long, straight coastline and met a narrow asphalt path running parallel to the sea, right by what looked like a hospital or nursing home. As the MCT map directed, we turned onto the path.

The path ran slightly elevated, lined on both sides with short young pine windbreak forests. In the distance, we could see several small man-made hills rising from the flat plain.

Climbing one of them, we learned that each was about 11 meters high and topped with a simple gazebo. Some of the benches even doubled as storage for emergency aid supplies. These artificial hills were built as evacuation sites in case of earthquakes and tsunamis — vital lifelines in this vast, flat coastal area where no natural high ground exists for elders to reach in time.

Beyond the evacuation mounds, the path connected to a perfectly straight, endless road that cut through the middle of—well, absolutely nothing.

Both sides were empty fields of dried yellow grass. The same short pine windbreaks stretched on and on beyond them.

We wished we could at least see the ocean to make the walk more bearable, but tall concrete seawalls completely blocked the view. The deep, rumbling crash of the waves barely reached us.

Several kilometers ahead, the road literally vanished into the horizon. Heat shimmered in the air, and road mirages rippled in front of us, making everything feel even hotter and more suffocating.

We’d thought the long riverbank road earlier had already been the day’s biggest physical and mental challenge, but no—there’s always something worse. At least on the riverbank, I could walk along the grassy edges for softer footing. Here, there was no mercy. Just sun, concrete, and more concrete.

Pretty soon, we started the battle against boredom, and also, my foot began to feel extra harder pains from the heated concrete.

It was a truly deserted area so remote from human lives. Only occasionally, less than a handful of cars and bikes passed. Only birds here were singing excitedly for some reason.

So randomly, I kept imagining the moors of Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte while limping along.

We felt really done for today. We only wanted this walking to end as quickly as possible, so we kept moving our legs without thinking.

Iwanuma Sheep Village

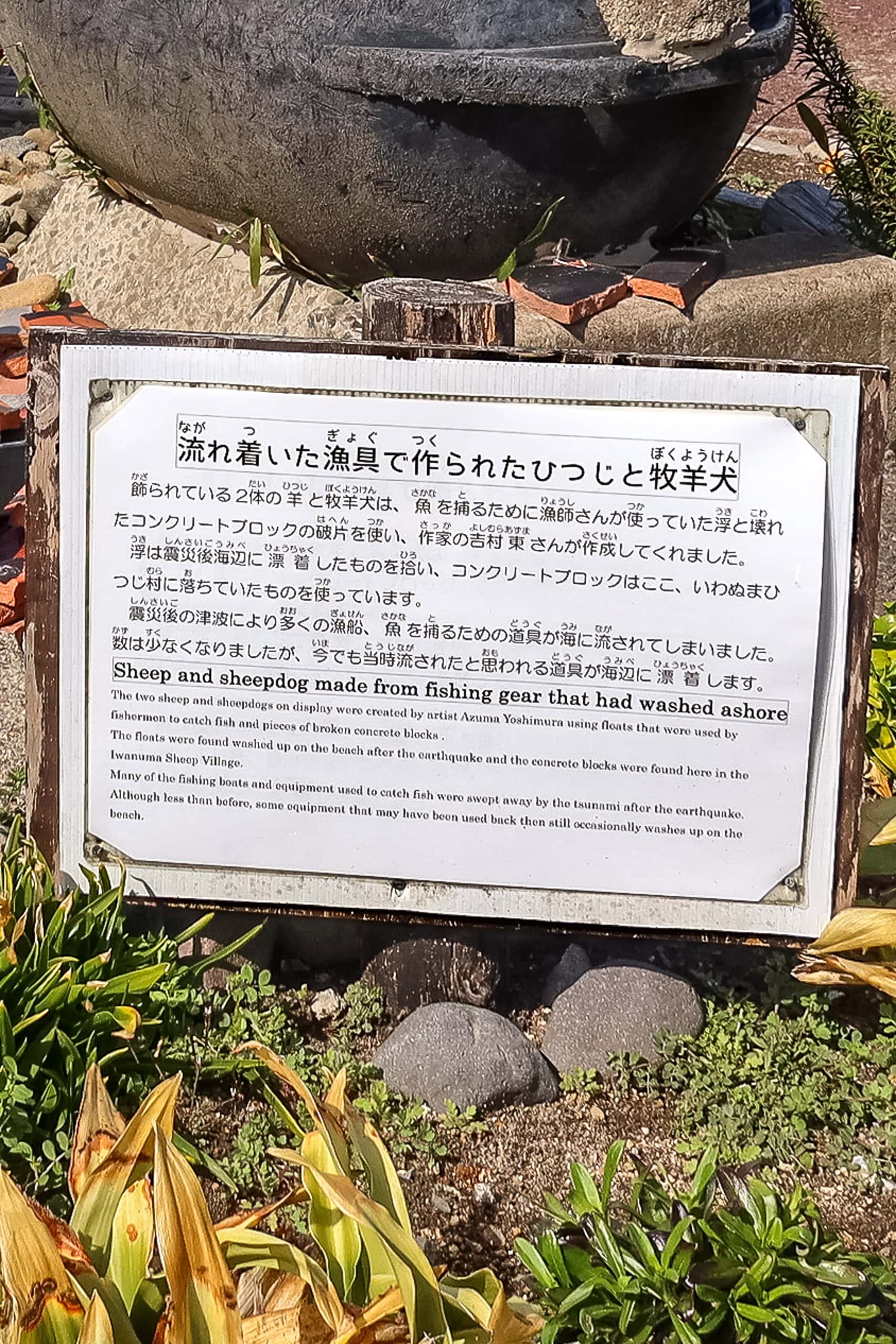

Then, out of nowhere, we spotted what looked like a big black buoy sitting in the corner of a field. Painted on it were a cute illustration of a sheep and an arrow pointing down a side road.

“Why sheep?”

“Wait — look, there’s another one!”

Erik checked Google Maps and found a place nearby called Iwanuma Hitsuji Mura いわぬまひつじ村. (Hitsuji means “sheep,” mura means “village.”)

Why on earth were there sheep here?

Google said it was only a three-minute walk away — hardly a detour — and curiosity won. Besides, whatever this “sheep village” turned out to be, any place open to the public had to have the thing we wanted most right then: a toilet.

In less than three minutes the roadside grass fields turned into paddocks.

“So… real sheep, then?”

Yes, it was. There they were — a whole group of sheep grazing inside one of the paddocks.

That morning alone we’d seen an olive orchard, walked through dry Mediterranean-like heat, and now, sheep. We started wondering if we were still actually in the Tohoku region of Japan — or if maybe my idea of “what Tohoku is like” had been wrong all along.

When the sheep noticed us outside the fence, they all trotted over, eyes wide with expectation. Visitors could buy feed, so we bought a cupful for their afternoon snacks. The silent but powerful “feed me” pressure from all those eyes was impossible to ignore.

The small toilet hut for visitors was surprisingly nice — clean, with colorful reused tiles on the walls. A few types of drinks were sold in the greenhouse-style entrance, and apparently there’s even a café open on weekends during the high season.

So, MCT hikers, take note: the sheep are here to save you.

The Long Walk to Sendai Airport

Feeling recharged, we returned to the torturously dull concrete road. After a while, to our great relief, the faint silhouette of Sendai International Airport 仙台国際空港 — our goal for the day — finally appeared on the horizon.

Just seeing it made us relax a little. With the finish line in sight, we decided to take a small detour and climb up the sea wall to see what lay beyond.

Instantly, it was cooler.

The ocean wind whipped across the top, and we realized how much breeze those tall concrete walls had been blocking from the inland side. We savored this brief heaven — the sound of the waves crashing into the breakwater tetrapods, the smell of salt air, the endless white spray.

As we drew closer to the airport, traces of civilization began to reappear. The MCT route curved around a pond and led into a large sports complex: Iwanuma Beachside Park 岩沼海浜緑地.

We were absolutely ecstatic to find a proper lineup of vending machines waiting near the park management office — and even an ice cream machine!

Between Okuma Station 逢隈駅 and this park — almost 15 kilometers — there had been no vending machines except the one at the construction site office.

We doubt that temporary office will still exist once the project finishes, so we were lucky to find it today.

Future hikers, take note: don’t count on it for your water supply.

Whether you’re walking northbound or southbound, make sure you carry enough water and food through this area. On the map, it looks like part of the city, but in reality, shops and vending machines are few and far between. We definitely underestimated that.

After the sports park and another short walk — less than two kilometers — we reached another park, Millennium Hope Hills Ainokama Park 千年希望の丘相野釜公園, built around a pair of man-made evacuation mounds.

This one had a more relaxed, picnic-park vibe. We spotted a clean bathroom and at least one vending machine near the parking area on the opposite side. Just beyond the park, a corner of the airport’s runways came into view — our goal was almost there.

The last standing house

The last kilometer to the airport crossed a huge grass field — nothing but a carpet of knee-high, dry yellow grass.

In the middle of it stood a lone house, like a ship floating on a yellow sea.

As we walked closer, we saw it was a half-destroyed home. Before the tsunami washed everything away ten years ago, this field had been a village with hundreds of houses. One in every eight residents was lost.

This house had somehow survived, standing amid the wreckage. After everyone left and the traces of the area’s history were cleared, it remained alone — the last proof that this place had once been a living village.

The house — the former Suzukis’ residence, 旧鈴木英二邸 — was already scheduled for demolition at that point and completed its “final mission” by the end of 2021. Today the former village is under redevelopment, so future hikers will see a completely different scene here.

We were grateful that we happened to pass by on this day, and could witness the house in its last moments.

According to the official MCT map, somewhere between the picnic park and this field of yellow grass we crossed our second municipal border of the day, entering Natori City 名取市 from Iwanuma — but once again, we didn’t notice it at all.

Honestly, we felt a little sorry that our memories of Iwanuma ended up being mostly hot, monotonous flat roads along the river and the walled coastline. The sheep village helped redeem the day a lot, though.

At last we reached Sendai International Airport — today’s goal. A train line runs from here toward the Natori Station area. Otherwise, there’s really no place to stay around the airport; we were surprised there weren’t any hotels by such a major regional hub. We booked a room at a national-chain business hotel in front of a big shopping mall, just two stations away.

Here’s hoping the MCT through Natori brings something more interesting tomorrow.

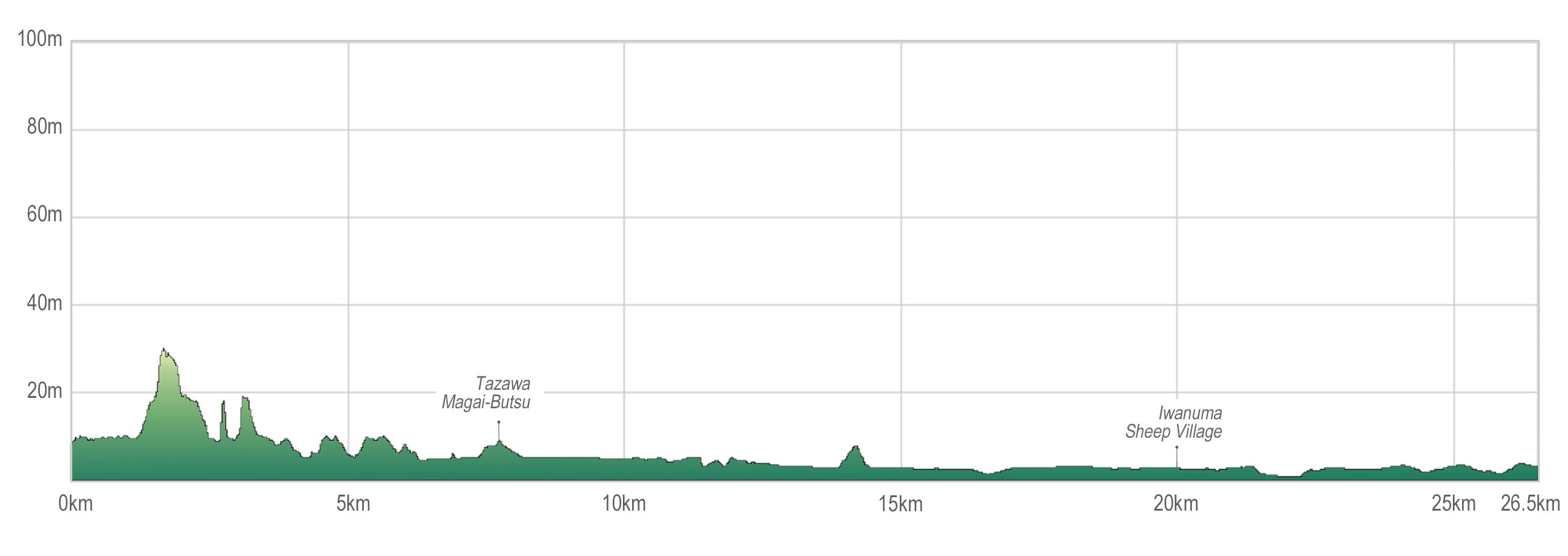

Day 4 – MCT

| Start | Watari Castle |

| Distance | 26.5 km |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 40 m / 44 m |

| Finish | Sendai Int. Airport |

| Time | 7 h 26 m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 30 m / 0 m |

Route Data

The Michinoku Coastal Trail Thru-hike : Late March – Mid-May 2021

- The first and most reliable information source about MCT is the official website

- For updates on detours, route changes, and trail closures on the MCT route

- Get the MCT Official Hiking Map Books

- Download the route GPS data provided by MCT Trail Club

- MCT hiking challengers/alumni registration

Comments