Two Days to Finish the Island Legs

MCT thru-hikers need at least three days to cover the official island sections. Those sections are concentrated in the southern part of the route, which means northbound hikers face the sea crossings early; southbound hikers hit them just before the southern trailhead.

We finished the first — the Urato Islands — two days ago.

Today (Day 9) and tomorrow we’ll finish the remaining two and be done with time-restricted ferries and island logistics.

Until we reach our goal — the north trailhead — in about 40 days, we’ll stay on the mainland with no special complications to plan around. That was one of the reasons we chose to go northbound.

The Ajishima Line ferries

The second round of sea crossings and island hikes took us across Tashirojima 田代島 and Ajishima 網地島.

Hikers need to take three ferries to complete this part. Starting from the ferry port in downtown Ishinomaki 石巻市, the route leads across the two islands and ends at Ayukawa Port 鮎川港, on the tip of the Oshika Peninsula 牡鹿半島.

Unlike the other two “sea travel and island hikes,” this section required no advance bookings. Instead, we used regular public ferries. The Ishinomaki municipal ferry, called the Ajishima Line 網地島ライン, connects downtown Ishinomaki, Tashirojima, Ajishima, and Ayukawa Port. Although Ayukawa lies across the sea, the Oshika Peninsula is still part of Ishinomaki City.

By contrast, for Urato Islands on Day 7 we needed a special MCT supporter’s fishing boat between Sabusawajima 寒風沢島 and Miyatojima 宮戸島 because Miyatojima belongs to a different municipality. Sabusawajima is part of Shiogama 塩竈市, while Miyatojima belongs to Higashi-Matsushima 東松島市 — which is why the Shiogama public ferries don’t go there.

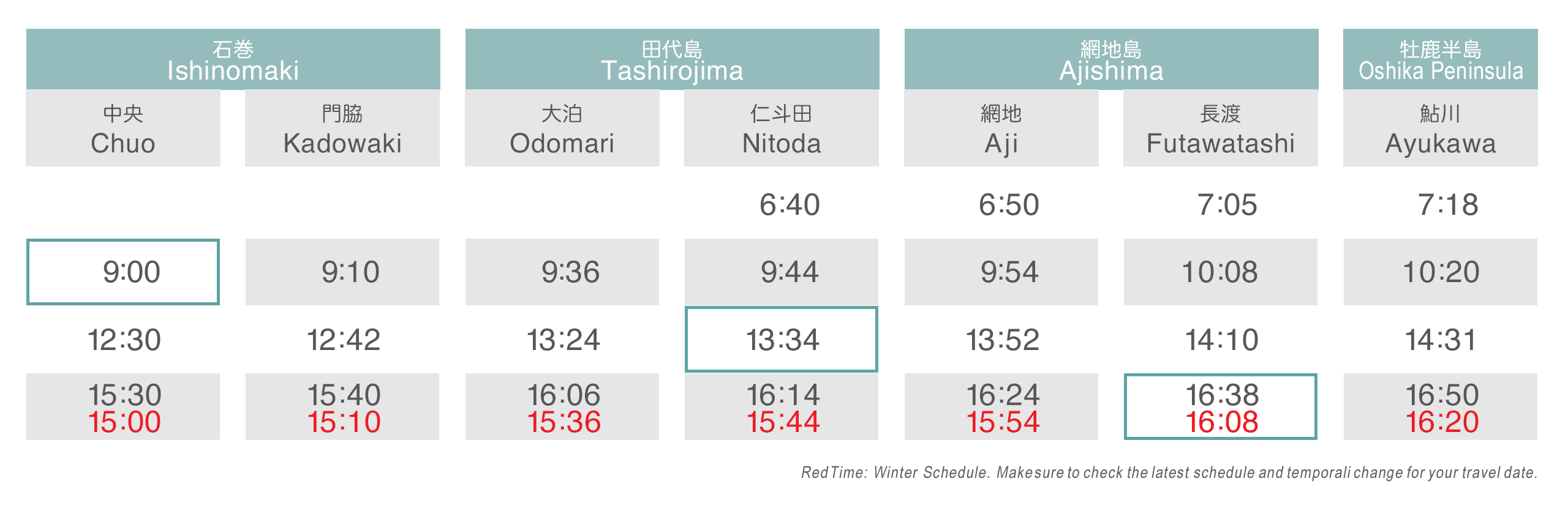

As the schedule shows, the Ajishima Line ferries run three to five times a day, depending on the season.

However, MCT hikers should note that only one specific set of ferries allows you to complete the full crossing in a single day:

| Departure | Arrival | Fee | |||

| 1 | Ishinomaki Chuo | 09:00 | Odomari – Tashirojima | 09:36 | ¥ 1,250 |

| 2 | Nitoda – Tashirojima | 13:34 | Aji – Ajishima | 13:52 | ¥ 350 |

| 3 | Futawatashi – Ajishima | 16:38 | Ayukawa | 16:50 | ¥ 470 |

Compared with the three Urato Islands we visited two days earlier, Tashirojima and Ajishima are much larger. The MCT route on each is about five kilometers.

In the Urato Islands, we could call on-demand boats to cross between the islands whenever we arrived at the docks — flexible and stress-free. This time, though, we had to catch fixed-schedule public ferries. Missing one would mean being stranded.

There seemed to be a few minshuku (family-run inns) on Ajishima, but since it was the off-season — and during COVID — we didn’t want to rely on luck.

The Second Islands Route Section On the MCT

The taxi we had arranged the night before was already waiting at the hotel entrance when we checked out at 8:10 a.m.

The quiet, experienced driver smoothly took us to Ishinomaki Chuo Port 石巻中央 by 8:25 a.m.

After purchasing ferry tickets from the ticket machine, we waited while the crew finished preparations and allowed boarding.

We bought tickets only to our first stop—Odomari Port 大泊 on Tashirojima 田代島—for ¥1,250 per person. We would need two more ferry tickets later in the day, to be purchased on board each ferry.

To our surprise, far more passengers than expected had gathered in front of the ferry—and then we realized it was Saturday. Even more surprising, most were young tourists in their late teens or early twenties, mostly couples on weekend dates. Others were young men carrying backpacks and fishing rods.

It was quite a contrast from the Urato Islands ferry two days earlier, whose passengers had mostly been island residents and workers.

The ferry departed and cruised down the final stretch of the Kyu-Kitakamigawa River 旧北上川. Before heading out to the open sea, it stopped briefly at Kadonowaki Port 門脇, where more passengers boarded after parking their cars nearby.

Under another sunny, beautiful sky, we stayed out on deck to enjoy the sea breeze for the entire thirty-minute ride.

The Cat Island – Tashirojima

Only a few people, including us, got off at Odomari Port 大泊港.

We were sure most passengers would disembark at the next stop on the other side of the island. Tashirojima, known nationwide as “Cat Island,” has become increasingly popular among young cat lovers. In fact, no dogs are allowed on the island.

Long ago, Tashirojima thrived on its fishing industry and had a large population. Now we saw only a few houses, and everything was eerily silent.

From its fame as the Cat Island, we had imagined crowds of cats waiting for us — like the internationally known Rabbit Island in the Seto Inland Sea, where visitors can see a literal sea of rabbits covering the ground.

Reality was different. We saw just one cat wandering around.

It probably knew most visitors got off at the other port and had moved in that direction — more efficient, after all. After one look at us, it quickly lost interest, realizing we had no cat food.

Beside a small weather shelter for ferry passengers stood a new island map showing the MCT route in dotted lines.

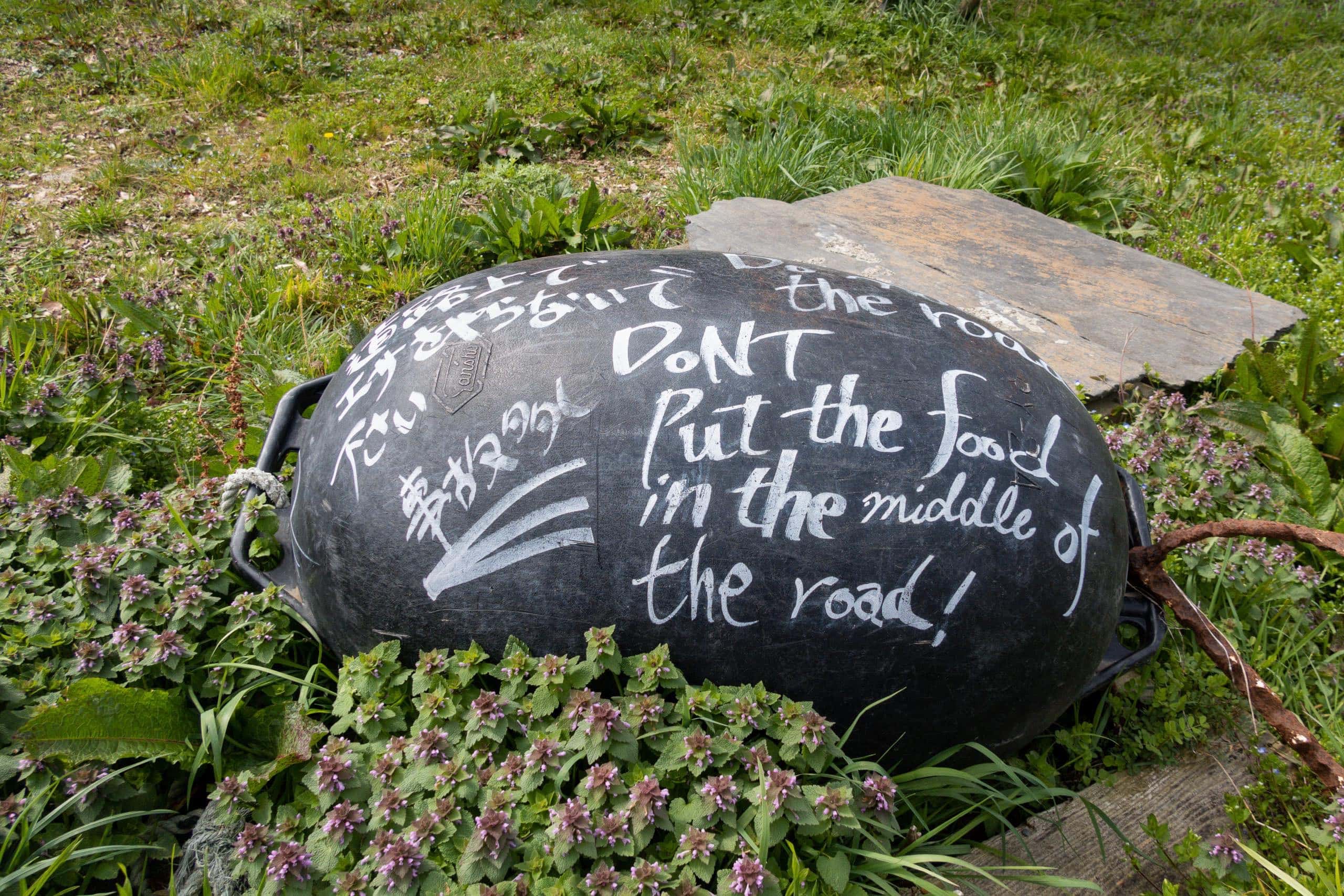

Another thing that caught our eye was a black buoy near a narrow path, covered with white letters. In both Japanese and English, it warned visitors not to leave cat food on the street.

We could easily imagine what had been happening before COVID: waves of tourists flooding this quiet island, chasing and feeding cats, leaving scraps of food scattered along paths that residents used every day. The uneaten food would rot, drawing flies and birds — and with them, plenty of mess.

Near the warning buoy we found a small folkloric site called the Kobo Daishi Well 弘法様の井戸.

“Look—apparently Kobo Daishi came even to Tohoku.”

“Of course, it’s Kobo Daishi!”

As residents of Tokushima 徳島県 in Shikoku 四国, and as pilgrims who have walked the Shikoku Pilgrimage 四国遍路 multiple times, we found this discovery amusing. It may be hard to understand why unless you know about the Shikoku Pilgrimage and Koyasan 高野山.

Across western Japan, there are thousands of legends about the great Kobo Daishi 弘法大師 and the miracles he was said to perform. Even when hiking in eastern or northern Japan, we rarely found a place without some Kobo Daishi site or statue.

We had half-jokingly kept track of the northernmost one—and this tiny island well in Tohoku set a new record.

Before following the MCT route, we noticed a torii gate and a steep stone staircase leading to a shrine.

As a warm-up, we climbed the stairs and found a small red shrine guarded by stout old trees.

Around the shrine and along the first part of the MCT route, the vegetation felt almost tropical despite the northern latitude.

We saw no trace of the island’s former prosperity; most areas seemed long abandoned and overgrown with forest. Yet, unlike the mainland, where litter is often an issue, the sparse population here meant the woods looked clean and orderly—nature’s own design.

The Cat Shrine

Naturally, the route signs here seemed designed for cat-seeking visitors rather than MCT hikers. We missed the first crucial corner where we should have turned right to stay on the MCT route — every wooden arrow at the junction pointed straight ahead. (Yes, we should have checked the map.)

As we continued along the narrow road, unaware we’d gone the wrong way, we saw a few young couples ahead feeding dried fish to several cats that followed them.

Soon we found a tiny white-walled shrine with rows of ceramic cat figurines in various shapes and sizes.

A few cats lounged in the sun at the corners of the shrine grounds.

It’s common to see more cats in fishing villages than in cities, where stray cat and dog control is stricter. Traditionally, people valued cats because they hunted mice that threatened stored food. In the early modern period, sericulture also flourished on Tashirojima, and cats protected silkworms from rodents.

Cats were further believed to bring good luck and large catches to fishermen. With abundant fish and a culture that cherished cats, the island became known as a feline paradise.

Unsurprisingly, the shrine we found enshrines a cat deity — Nekogami-sama 猫神様.

According to the information board at the shrine, one day fishermen were breaking rocks to make anchors while friendly cats lingered nearby as usual. A fragment flew off and struck one of the cats, killing it instantly. Heartbroken, the fishermen built the shrine to honor the cat and to pray for the safety of all cats and for continued good catches.

The Cat café At The Highest Point On The Island

Still unaware we had taken the wrong path, we walked through thick walls of slender bamboo lining both sides of the road until we reached a former elementary school that had been turned into a café and cat-goods shop, Shima no Eki 島のえき.

On the front deck, more young couples were stroking and patting cats, while others lounged or napped nearby.

A vending machine stood outside, so we bought drinks and took a break — and finally realized we had come the wrong way.

The road we’d followed was the direct route connecting the island’s two ports. The former school cat café was close to the other port, which explained why most of the young visitors from our ferry had come from that direction.

We had to walk back to the point where we’d missed the turn—but it wasn’t all bad. We still had plenty of time before the next ferry. The cat shrine and the cat café weren’t on the MCT route, so if we’d stayed on course, we would have missed two of the island’s most popular spots.

The correct MCT route follows more of the island’s outline.

On this side, there were no signs of houses or daily life. The flatter areas were covered entirely in dry grass along a concrete-paved farming path. These fields, bathed in sunlight, must once have been rice paddies or vegetable plots. Beyond them, the blue ocean shimmered in the distance.

Cape Mitsuishizaki

The strangest thing about the MCT route on Tashirojima was that it didn’t pass the island’s most famous spots—the cat café and the cat shrine.

The strangest thing about the MCT route on Tashirojima was that it didn’t pass the island’s most famous spots—the cat café and the cat shrine.

We also had to take short side trips to see other scenic places.

Along the way, we passed a few traces of the island’s former glory, but most information boards were rusted, and fallen signs lay scattered on the ground.

A dusty, rather eerie-looking portable toilet stood beside the path with a sticker reading pay toilet. We couldn’t figure out how we were supposed to pay — and frankly, we were too scared to open the door — so we left it untouched.

At a fork, we spotted a small sign pointing down a forest path toward Mitsuishi Kannon 三石観音, about 400 meters away. On the official MCT map, this junction was marked as the “Turn for Cape Mitsuishizaki 三石崎.”

After checking our walking speed, distance, and time before the next ferry, curiosity won out and we took the detour.

The Kannon temple itself was less impressive than expected — tiny and relatively new. The earthquake ten years earlier had probably destroyed the original building, whose weathered wooden remains were slowly returning to the earth behind the new hall.

Still, we were glad we came: the cliffs and the ocean view from there were breathtaking.

One of the cliffs had been developed as a viewpoint with a small gazebo. Three different camping setups stood among the pines, while the campers themselves fished from the wave-washed rocks below.

We walked another 400 meters back to rejoin the MCT route. By then, we were roughly halfway across Tashirojima.

The rest of the route was much the same—narrow paths hemmed in by bamboo walls and pine woods, simple and quiet.

MANGA Island Campfield

The last notable site on Cat Island was MANGA Island Campfield マンガアイランドキャンプ場.

According to travel websites and magazines, this place is popular because all five lodges are cat-shaped and feature cat-themed interiors.

Each lodge has bunk beds, a small kitchen, a toilet, and a shower room—perfect for groups of cat lovers.

Unfortunately, we were here in the off-season (late April to the end of October), so both the lodges and tent sites were closed, and no one was at the administration office.

We simply walked around for a bit, enjoying the clear view of the next island, Ajishima, across the blue water before heading down to the port.

This side of the island was noticeably more populated, with many more houses. Still, the population on this aging island is only about sixty people—and twice as many cats. That means most of the homes we saw were probably unoccupied. From start to finish, the island was quiet except for the sound of the ocean and the occasional laughter of tourists.

We waited for the next ferry while studying a handmade information board. A green arrow pointed to “few cats,” and a red one to “many cats”—the most vital information for any visitor here. But the newest-looking note was the most important: it said “Do NOT feed the cats.” It explained that human food or excess cat food could make them sick. The board even had graphic charts showing which foods are harmful — or poisonous — to cats.

A few local elders with handcarts waited by the ferry dock. When the ferry arrived, crew members handed them boxes and bags — probably daily necessities they’d ordered, since we hadn’t seen any grocery or household shops on the island.

When the ferry docked, many young travelers cheerfully got off. Meanwhile, a few couples on the pier didn’t board, likely waiting for another ferry directly back to Ishinomaki 石巻市. In the end, we were the only passengers getting on.

The Ajishima Island

The second island of the day, Ajishima 網地島, felt livelier as our ferry approached the northern port, Aji 網地.

That impression might have been colored by a cheerful family with two little girls on the same ferry. As soon as we docked, the girls spotted another family waiting on shore—a child their age waving wildly. Shrieking in delight, they dashed off the ramp to meet her. Friends or cousins, they threw their arms around each other, laughing.

It was heartening to see children on the island. In fact, the population here is just under 300 — still far more than on Cat Island, where only about 60 people remain.

The ferry waiting room was a small fish-shaped hut with a bathroom.

Before following the MCT route, we stepped onto the white-sand beach beside the port. Aji Shirahama Beach 網地白浜海水浴場, famous in Ishinomaki for its clear emerald-green water, is packed with swimmers in summer. But in early spring, we had it entirely to ourselves, watching the calm waves wash the empty sand.

At one corner of the beach stood three stone monuments and a bronze statue of a Western man.

The Denmark-born explorer Vitus Bering led a Russian expedition here in 1793. The crew exchanged goods — perhaps food and water — with islanders, and the encounter is now recognized as the first Russia–Japan trade in history.

The MCT route on Ajishima alternates between two types of paths: unpaved forest trails of bamboo and native trees, and a long, straight section of main road connecting the northern and southern villages. A broad stretch of wilderness separates the two, with the road cutting through like a backbone.

Paths between houses in fishing villages are usually narrow and winding. Following the MCT stickers and ribbons tied to poles and fences, we navigated through the quiet settlement.

The signs eventually led us into dense thickets of tall, slender bamboo that arched overhead into a tunnel—one we might have hesitated to enter if it weren’t so clearly marked.

The forest walk that followed was lovely, full of flickering light and shadow through oddly shaped trees.

But soon the path rejoined the paved two-lane road, and we had to walk more than twice that distance along it.

We passed a former school that seemed to have been converted into a youth camp or field-trip facility — not open to the public, unlike the cat café on Tashirojima.

Instead of following the last several hundred meters of road, the MCT route veered into the forest again, tracing an old unpaved farm track that wound for about two kilometers before rejoining the main road.

If you’re short on time, you can skip this detour and stay on the straight road.

From that rejoining point, the MCT route continues along the main road, descending toward the southern port, Futawatashi 長渡.

Dowamekizaki Cape

We checked the clock to make sure we had time to see the Dowamekizaki lighthouse, which I’d noticed on the information map at the north port.

The lighthouse stands on the island’s south edge, and visiting would add about 2.5 extra kilometers out-and-back. It looked doable if we walked a bit faster and didn’t linger too long.

We turned onto a side road through the south village. With nearly 300 residents on the island, the houses here looked far more lived-in.

The red-and-white, candy-striped lighthouse looked charming against the deep blue Pacific — like a big pepper grinder on a blue tablecloth.

The cape’s name, Dowamekizaki 涛波岐崎, is notoriously hard to read even for Japanese speakers. One origin story traces it to dowameki, a word describing the thunderous roar of wild waves battering the cape — and that was exactly what we saw beyond the lighthouse.

We followed a narrow path down to the cliffs. The scene was wondrous: the waves heaved and boomed, and the sound rolled under the warm, slanting light.

Looking left, we had a crystal-clear view of a massive, mountain-like island rising straight from the sea — Kinkasan 金華山, the last and hardest-to-reach island on the MCT route, which we planned to hike tomorrow.

We’d budgeted twenty minutes at the lighthouse, but the views around the cape made us forget the time.

Suddenly we had only twenty minutes left to make the final ferry, so we ran the last 1.5 km back to the port.

Erik likes running and goes regularly. Me? Not so much.

Still, I had no choice. I ran—truly ran—for the first time in many years, with a heavy pack on my shoulders. My days in the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force felt like ancient history, and I’d done no real training over the winter, sitting at my computer most days.

But I ran. Otherwise we’d be stuck on the island overnight.

But I ran. Otherwise we’d be stuck on the island overnight.

We made it — helped by the steady downhill.

The ferry was late — so late we started to worry we’d missed it.

Just like on Cat Island, local elders with handcarts were gathered at the dock, chatting as they waited. It was a good sign: the ferry would bring the supplies they’d ordered.

My heart was thumping; I was completely out of breath after the sprint. I did my best not to cough like crazy — standing among elders on an isolated island in the middle of COVID anxiety across Japan.

Ayukawa Port

There were only a few passengers on the ferry to Ayukawa Port 鮎川港, so we sat on the empty outer deck to say goodbye to the two islands as the ferry sped through the waves toward the mainland.

When we searched for accommodation in the Ayukawa area, everything near the port was either fully booked or temporarily closed.

Normally, guests at the local family-run minshuku inns are leisure fishers or construction workers helping to rebuild disaster-affected areas. It wasn’t their busy season yet.

Many of the minshuku owners are fishermen themselves, and this time of year seemed to be their seaweed-harvesting season. They were simply too busy to host guests.

After zooming in and out of Google Maps and simulating possible route options, we found a hotel a little farther from the port that offered free pickup and drop-off for guests. We booked two nights there and arranged the pickup times and meeting points for the next two days.

We had told the hotel we’d be taking the last ferry from Ajishima. When we arrived, we immediately spotted a car and a polite man waiting just outside the port gate. He recognized us right away—not only because there were so few passengers, but also because it’s hard to miss an unusually tall Dutchman.

On the way to the hotel, we passed a lively campground. It was Saturday evening, and the sites were packed with family tents and cars, with groups enjoying barbecues in the cool air. Since the start of the COVID era, campgrounds like this have been busy everywhere in Japan — families and friends gathering outdoors where they can relax safely.

The hotel stood on a hillside opposite Kinkasan Island 金華山. From our room window, it looked so close that a good swimmer might almost cross the channel.

Yet this is the island many hikers struggle to reach — and many past thru-hikers end up skipping.

We call Kinkasan the hardest and most expensive island on the MCT.

Why?

…Well, that story comes next.

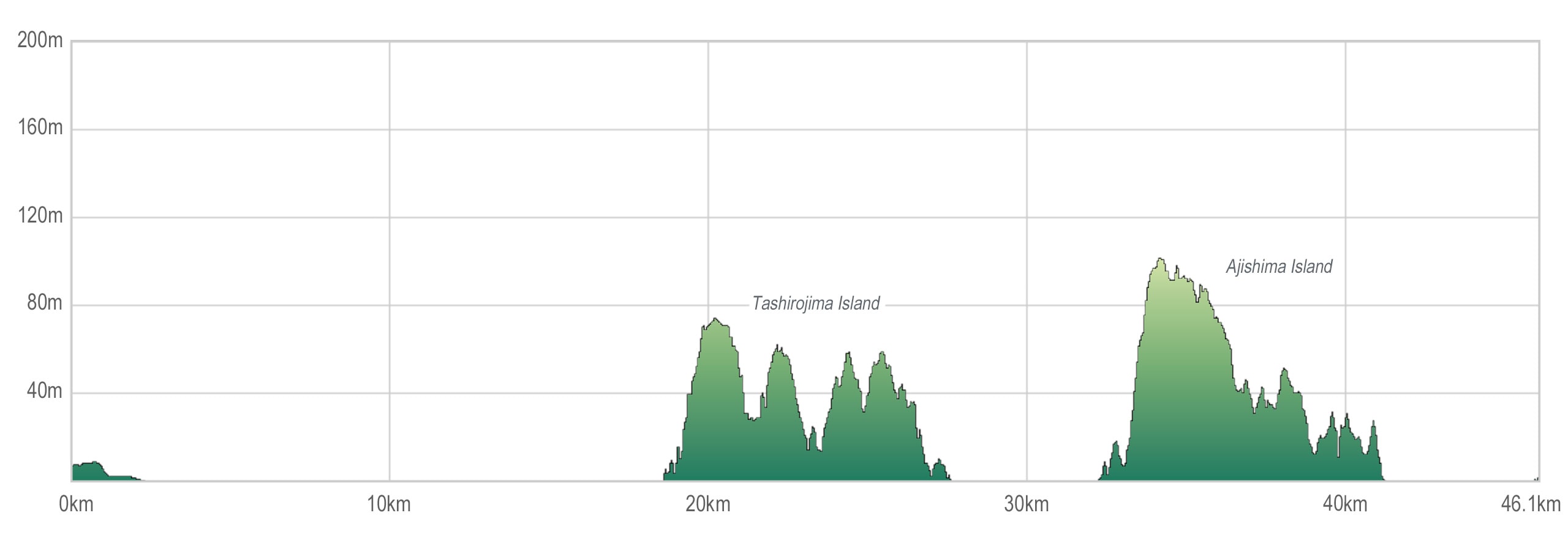

Day 9 – MCT

| Start | Ajishima Line Chuo Port |

| Distance | 46.1 km (Walk: 28.8 km) |

| Elevation Gain/Loss | 373 m / 176 m |

| Finish | Ayukawa Port |

| Time | 8 h 6 m |

| Highest/Lowest Altitude | 106 m/ 0 m |

Route Data

The Michinoku Coastal Trail Thru-hike : Late March – Mid-May 2021

- The first and most reliable information source about MCT is the official website

- For updates on detours, route changes, and trail closures on the MCT route

- Get the MCT Official Hiking Map Books

- Download the route GPS data provided by MCT Trail Club

- MCT hiking challengers/alumni registration

Comments